Life on the rock

For the inhabitants of Niue—a knuckle of coral in the emptiness of the South Pacific—existence is precarious. A threadbare coat of soil, a tenuous supply line from distant New Zealand and regular battering from cyclones make the upraised atoll a home from which many are drawn by the prospect of greater economic rewards in Auckland. Yet a determination among its faithful residents to keep alive their culture and traditions may see tourism—managed by the islanders on their own terms—the saviour of this ocean-bound wilderness.

Taumafai Fuhiniu Expertly nudges his outrigger across the dimpled swell, his T-shirt a slice of pineapple against the copper-sulphate sea. A sea that is hyper-blue. Swimming-pool blue, indigoed where his shadow overlays its surface. I strain to keep pace with his paddling, which, despite his canoe’s turn of speed, seems dreamily inattentive. I comfort myself with the thought that, in taking his father’s vaka for myself, I have an inferior vessel. Fai slows, eyeing the shore and the tufted skyline of palms where the village of Alofi gathers itself together in the vicinity of Niue’s only wharf. A few kilometres to the north, waves break into silent plumes against a sheer limestone bluff. It is five forty-five, give or take.

I am out here with Fai because I want to feel the rhythm of an island morning and to reawaken in myself those ancestral stirrings occasioned by the hunt for breakfast. I am here because I want to connect with the life that gets lost when you leave a fleck in the South Pacific for wage work in a city of motorways and late-night malls. All right, I’m here because ever since running my hand along the hull of a canoe I discovered resting high and dry in Avaiki Cave, I have wanted to get out into the deep in one.

The fact is, in Niue you don’t have to go far from shore to be in serious water. The island, some 260 square kilometres of upraised coral, is hemmed along most of its 64-kilometre coast by a fringing reef 60 or so metres wide, though the sea in places runs right in, slamming up against the island’s towering cliffs. Beyond the fragile reef everything plunges precipitously to oceanic depths.

With no surface runoff to speak of, and therefore little nutrient wash, Niue’s sea mount is, in the opinion of people paid to study such things, relatively barren. Having spent time snorkelling among countless species of reef fish in the island’s coral forests, encountering turtles, sea snakes and—just once, cruising with predatory grace—a white-tipped reef shark, I find it a hard judgement to reconcile.

Weeks before my visit, New Zealand sportfishing journalist Sam Mossman played these waters, hauling up red bass, almaco jack, jobfish and, from a four-metre “tinny,” a majestic 55 kg sailfish. Mossman was, however, quick to discount the idea of Niue as a “red-hot” billfishery. The locals, who considered his tally better than average, reckoned he had been lucky. Both Mossman and I visited in the dry season, when the south-east trades blow gently over the island. December to March, the wet season, is not so clement, and fishers can lose 50 or more days a year to rough seas.

Earlier in the day, Fai spoke with bitterness about the impact of foreign commercial deepwater fishing in Niuean waters. And to what end? The government received a mere $60,000 a year for the fishing concessions. “That’s peanuts,” he said. On Fai’s return from New Zealand in 1988 the fishing was good. These days he is thankful to get anything.

We sight another fisher in an outrigger, stooped over his lines, his straw hat giving him the appearance of something organic, like kelp, riding the swell. His left arm is wrapped around the paddle shaft, his hand almost in the water as he holds it vertically, keeping on station with an occasional well-judged stir of the blade.

“That’s Dr Harry,” says Fai respectfully. “One of the last surviving old fishermen.”

We draw alongside, and in the strengthening light old Dr Harry Nemaia nods a greeting. Like all Niueans, he has aged well, his 75 years refining his features to hoary nobility. We fall into conversation, the way you do in a place like this. He tells me he has been fishing these waters since he was a boy of 12, and that in those days a morning such as this would see 15 or 20 canoes in the water. A few days ago, here in what he says is one of the best grounds, he caught a small yellowfin tuna. He doesn’t hold out much hope today. The current, he says, has been bad for weeks.

Hake mai! Hake mai! Ha ika kili kahi. Ha ika ulutafatalei.

Come up! Come up! Oh dark-brown fish. Oh barb-headed fish.

An aluminium runabout cuts past inshore, heading south to another ground. Fai and Dr Harry eye its raw bouncing passage without comment. It is yet another sign of the times. We allow ourselves to drift back, leaving the doctor to his lines. Fai has mackerel on the hook at 30 fathoms and strip bait at 25. “You need to find the thermocline the fish are in and work it,” he says.

In former days this pelagic toil was helped by the chants.

Oh grey-backed fish. Oh black-backed fish. Oh rough-backed fish.

Back then, before metal traces and metal hulls, flying fish were caught at night with hand nets from canoes, their attention drawn by smouldering torches of kafika wood. Fishing lines of spider’s web were also used, and cuttlefish lured with fake rats.

As we rise and fall with the swell, I think of Fai’s earlier disdain for poorly kept neighbouring craft as he removed the coconut frond covers from his own canoe and carried it to the sea. “I don’t worry if the wind is strong, only if the gear is not right,” he said, advancing with wiry agility and setting the vaka decisively in the foam. He admitted to having once braved a force-seven gale in order to keep an eye on his fishing father.

He knew what could happen out there. Once, his dad, Nokupega, had been set upon by a tiger shark and had seen his boat demolished under him. It was in the southern grounds, where many fishers have lost their lives. That day, Nokupega had made it back to land unharmed. Back to Niue. To the Rock.

It was in Fai’s nearby bush garden, as we strolled amongst neatly cultivated plots and ageing forest trees, that I was introduced to the world of Pacific marine technology.

“This camphor tree is for the paddle, and the le here,” a slap to the trunk, “for the top of the canoe. The wild hibiscus, that straight tuber there, is for the outrigger—your life vest.”

Ten years ago, when he and his father resettled in Niue after years of wage work in suburban Auckland, they helped revive the art of traditional fishing on the island. Fai has built 43 canoes since returning, having learned the skill at Nokupega’s side. Setting aside the traditional clam adze in favour of a steel axe, he claims to have fashioned a canoe in less time than it took three people with a chainsaw, taking just 80 work hours from standing timber to floating hull.

Suddenly, in front of me, Fai’s line is tight and his finely chiselled face is all attention. The line angles out and carves an arc across the water.

Oh striped fish from the bottom of the deep.

His canoe begins to pirouette, and I’m all over the place—a confusion of lashed timbers and contrary eddies—as I try to get closer. He pulls in the nylon metre by slow metre, then finally strains, and the hooked fish, a streamlined wahoo, is lifted out of the inky sea, its scales newly minted in the brilliant sun. Fai raises his club.

Under the canoe, maybe three metres down, a pale torpedo flicks away—a second wahoo. The tail of the caught fish thuds the hull once more and it is over. We turn our prows for home, leaving old Dr Harry still bent over his gear. Despite the burden of Fai’s 18 kg catch, I find it hard to keep in his wake.

[Chapter Break]

Niue sits at the same latitude as Suva, but on the other side of the dateline. Its nearest neighbour is Tonga, 386 km to the west. To the east lie the Cook Islands, and to the north, Western Samoa. New Zealand is south-west, at the end of a 2400 km transport lifeline. Not much more than a thumbprint on the vast plain of the Pacific, Niue is at once one of the world’s largest coral islands and the smallest self-governing state. Consecutive geological lifting has resulted in a coastal terrace 28 metres high which rises abruptly from the sea, and, further inland, a second terrace some 70 metres above sea level. The island’s 14 villages, linked by a coast road, have all been built on the outer terrace.

Once on Niue, it doesn’t take long to work out what matters to the people who live here. Indeed, I began to work out what mattered within an hour of arriving, when everything in my room started turning to jelly. The table I was sitting at did a liquid shuffle in the opposite direction to my chair, and the ceiling beams began to chatter. I stood to go outside, thinking the wind might be getting up or that I was on the cusp of some sort of visitation, but I found that my feet could no longer walk convincingly. Within a minute or two the disturbance was over: an earthquake measuring 6.5, caused by some sort of altercation between tectonic plates in the Tonga Trench.

When it comes to natural phenomena, however, earthquakes aren’t the major cause for concern on Niue—this was the first one in over a year. Wild weather is. The island is on the fringe of the hurricane belt, and in recent years a series of storms have taken their toll. In the 1960s, following massive damage, the New Zealand government funded the building of the plain but sturdy concrete-block hurricane-resistant houses that now line every village street.

In 1989, a cyclone decimated the island’s coconut plantations, and the following year a more serious storm, Cyclone `Ofa, put paid to the passionfruit vines and lime trees. Divers can today still see the damage caused by `Ofa, which smashed swathes through the delicate coral, snapping off fine florets and shaving encrusted outcrops of rock to an unsightly stubble. On the lawn of Alofi’s refurbished Niue Hotel, huge boulders lie where they were heaved up over the 20-metre cliffs by `Ofa’s fury.

The day after my arrival, Ida Talagi of the Tourism Office showed me around her patch. Born on Niue, she left when she was four years old, returned from Australia for a six-week holiday in 1996 and stayed until her ticket ran out four months later. Back in Australia, she felt the tug of home and returned again to settle.

As we drove along crushed coral roads scorched white in the sun, through villages and forests, past plantations and signposted tourist spots, Ida spoke passionately of this island where, it seemed, each house we passed was home to a first cousin. Everywhere, frangipani was breaking into bloom along with bougainvillaea, hibiscus and orchids. Here and there, in a clearing, stood a roadside grave, marked with a simple inscription and a spray of flowers. In the villages, which appeared as sudden outposts of habitation amid the lush bush and arching palms, children waved and fowls scattered into undergrowth at our passing. Strips of pandanus for basketwork hung drying against concrete walls, and once or twice a woman could be seen weaving in the shade of a balcony. Then, beyond the last house, the green shutter would close once more, plunging us again into an unpeopled wildness. Although on the coast road we were never far from the sea, it remained reclusive, hiding its immensity behind a narrow fringe of trees and offering only an occasional tantalising glimpse.

Journeying along Niue’s inland roads, often through the virgin forest which still covers a fifth of the island, we came across the drifts of scrub and freshly cleared ground which mark the years-long cycle of talo harvest and fallowing. In one field stood an unattended bulldozer, an intrusion of modernity into a generations-old way of life. For 75 New Zealand dollars a landholder could have a plantation cleared, I was told, but at the cost of lost landmark trees and with the likelihood of acrimony over land tenure. ‘Dozer advocates, however, claim the machines are kinder to soil than the traditional practice of slash and burn.

Perhaps more worrying is the increased use of agricultural chemicals, some banned in New Zealand, which may be contaminating the “lens” of fresh water—Niue’s lifeblood—that lies some 20 metres beneath the surface. The threat wasn’t a visible one, however, and in places the island seemed a cornucopia.

“Here, if you go on a picnic, you just take a bushknife,” Ida said. “You’re never far from food.” A machete opens coconut and pawpaw, cuts talo, slices fish.

But despite fish in the sea and well-fed poultry in the villages, people hanker after tinned salmon and imported frozen chicken, she told me. Niue has become a consumer society propped up by official New Zealand aid and by remittances from Niueans working overseas. The challenge facing her, and all Niueans living here, is to find prosperity without destroying the fabric of Niuean life. That fabric is a tapestry stitched with traditions such as ceremonial ear-piercing and hair-cutting and rules controlling fishing and swimming; it is the sounding of the village drum on mail day and the four-square presence of the church at the heart of each community—the “anchor” which holds daily life. Without these, and a hundred other customary ways, Niue would quickly degenerate into just another offshore island; a piece of New Zealand inconveniently distant and economically of little consequence.

At Limu, where some of the island’s best snorkelling is to be had, Ida and I stopped to look at the coral pools, electric with fish in the midday sun. Thatched fale stood here and there among the rocks, their sheltered tables suggestive of a resort. At the reef, just beyond which humpbacks sometimes disport, the sea broke boisterously. We were alone.

“I want to help look after our environment,” said Ida, studying the swirl of fish. “I wouldn’t like us to end up like Fiji, losing our culture and our identity.”

[Chapter Break]

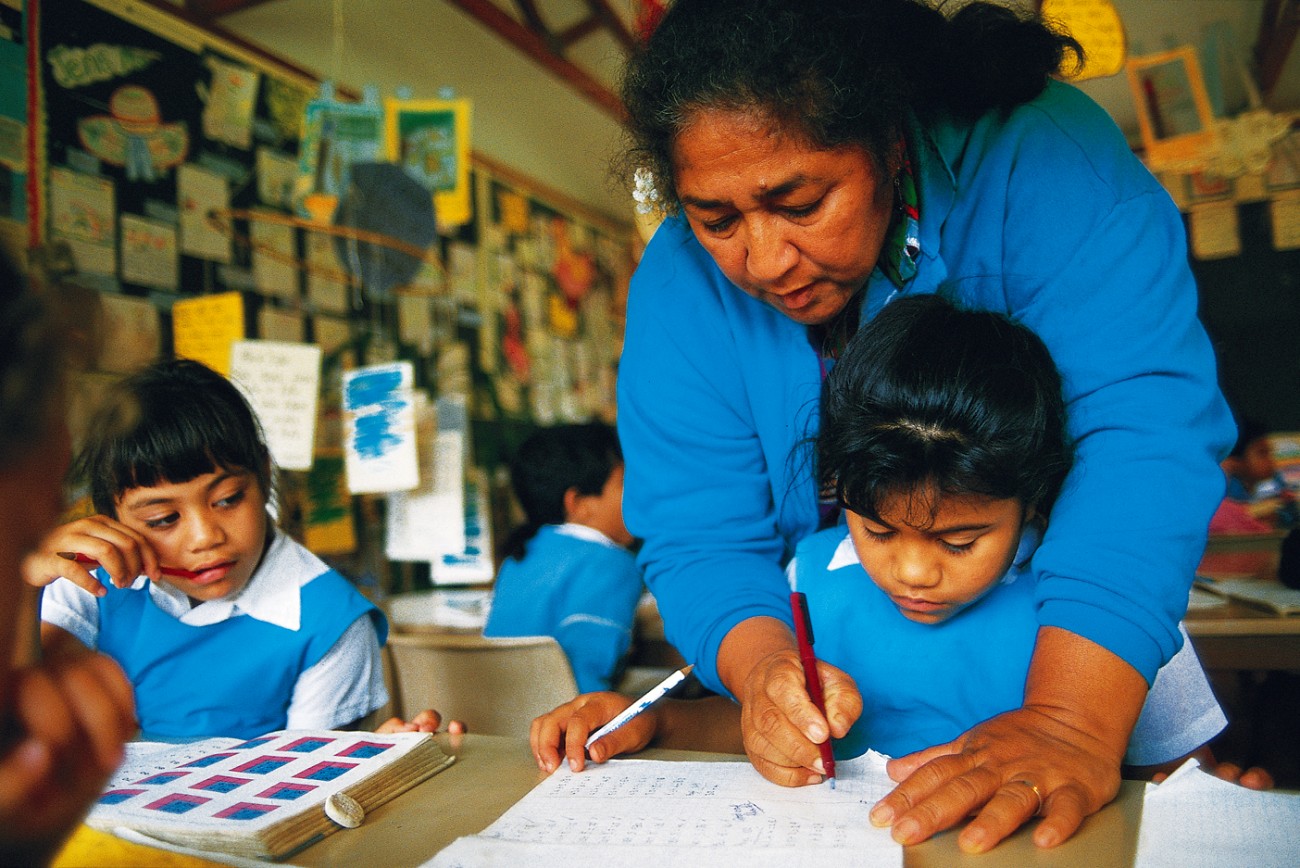

There is perhaps no place on earth so vulnerable to the ebb and flow of people in search of work as Niue. House after house stands empty amid the vibrant greenery, their windows staring blankly across overgrown yards or hammered shut with sheets of rusting iron. So many families have left the island that, on the rugged and exposed east coast especially, the villages seem at first sight to have suffered an outbreak of pestilence or some other natural calamity. The 1991 census showed 14,424 Niueans living in New Zealand, half of them under the age of 20. That is more than six times the number on Niue itself, where the population has dropped a further 15 per cent in the past three years to 2076. Of those living on the island, more than a third are below the age of 15. Most of those staying in New Zealand live in Auckland, many employed in manufacturing or community work.

Those who remain on the island labour to chisel gardens from the unyielding coral landscape. So little is grown that, apart from produce for export and personal consumption, only enough food is grown to sustain one weekly market.

Some locals are bitter that Niueans who show reluctance to return should continue to have a say in the affairs of the island. In Niue, all land is owned by the magafaoa—the extended family—and cannot be alienated except by transference to the crown. Appointed guardians, leveki magafaoa, must consult all family members whenever anything concerning the land needs to be settled. The exodus of so many Niueans has made this process difficult, and, in the opinion of some, has shackled land reform and economic development.

Then there is the rancour over Vaiea. An all but deserted village near the south coast, Vaiea is home to a handful of Tuvaluans, resettled on Niue from low-lying atolls threatened by rising sea levels. At a time of job scarcity on Niue, the policy has been roundly criticised.

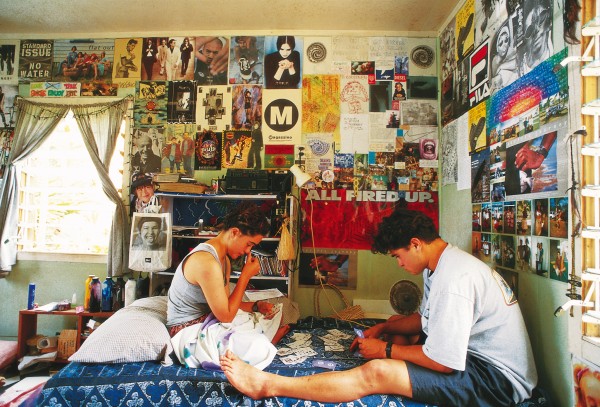

Niuean writer and artist John Pule caught the heartache and dislocation caused by emigration in his 1992 novel The Shark That Ate the Sun.

“Yes, it felt good to be able to buy things, to buy alcohol, food and clothes, anything, spending money doesn’t matter, as more will fill these hands, I can still see the fields and rocks on them, the cracks where the dark soil has cemented itself with the vegetation into the flesh, never ending, the gold dream, working in a white world where things are done differently.”

That is Puhia speaking, a Niuean who left his homeland in the 1960s post-hurricane exodus for a better life in New Zealand, where Niueans have dual citizenship.

“For the first few weeks or months the Polynesian always found his way to the sea, to see it and feel the water, to dream of the coastal reefs, stooping out of the canoe, lifting it up; taking it over the reef and out to meet the swells. The excursions to the sea were replaced slowly by going to these shops.”

Ida’s words suddenly sound again as I type these lines, and it occurs to me that the same process is beginning on Niue itself; that the sea is starting to be backgrounded by the shop counter, by shop culture.

The island imports some 15 times as much as it exports. Long after self-government, Niue remains economically dependent on New Zealand for everything apart from food staples and basic construction materials. “A sad fish on a steel hook,” John Pule called it.

John was born in the easternmost village of Liku, and, like the Puhia of his novel, migrated to New Zealand in the 1960s at the age of two. For the past 15 or more years he has set about excavating that past, wrestling with the effects of European contact on island life and with what it means to be a Pacific Islander immersed in a foreign culture.

Just weeks after my visit, John returned to Niue to run a writers’ workshop and to exhibit lithographs at the Tahiono Gallery in Alofi’s commercial centre, a grass square bordered on one side by the ring road and on the other three by a U-block of modern single-storey shops and government offices.

The gallery is run by expatriate New Zealander Mark Cross and his wife, Niueanborn Ahitau Makaea Cross. In a rare piece of symmetry, Mark now lives in Liku himself and champions John’s work.

One Sunday afternoon I took one of the newly sealed inland roads to see them. Sunday on Niue is a day palagi can find testing. By law, fishing is prohibited, and the locals give themselves over to churchgoing and visiting. Having earlier in the day been to a service in the Ekalesia Niue church in Makefu and now setting out on a spell of visiting, I felt I was slipping into that local groove nicely.

Thanks to its remoteness, Liku has a reputation for being a rebellious, backwoods sort of place. It was the last village to succumb to Christianity last century and its people are still known for their outspoken independence. Maybe those are just the things to attract the artistic temperament.

I arrive in Liku to find Mark out back tending chicken on a smoking fire. Inside are plates of coconut crab, talo and salad, along with some crayfish he caught the night before. I’m surprised at the crays. Getting any food from hereabouts is no easy featLiku lies on Niue’s windward coast, an exposed stretch of land whose sheer rocks and spectacular chasms make even reaching the water problematic.

Mark first spent time on Niue in 1978, and came back with his wife and their four children in 1995. “He told me we were only going to be here for six months and that we would be home for Christmas, so we didn’t pack much,” Ahi says, raising an eyebrow. “And we are still here.”

Mark, all asweat in the afternoon heat, contentedly pokes the meat. “He’s much healthier here,” she adds, glancing his way. “He’s asthmatic”

I ask Ahi if she thinks of going back to New Zealand. “I can’t. I’m on the village council.” Her eyes narrow mischievously.

After the meal we slump back in the seats outside. The fire has reduced to embers, and the day’s heat has been temporarily drawn by a sprinkle of rain.

“Sunday is a quiet day—unless someone dies,” says Mark. “Then you get the sound of the compressor as they dig the coral. You have to bury the dead quickly here. There’s no morgue.” There is a hospital, though, the Lord Liverpool, with a new one on the drawing board. With serious cases, patients are airlifted out to New Zealand.

Mark and I mosey over to his studio across the wet grass. The building once belonged to an uncle. On a fading sign at the door are the words: Brothers Fiafia Sports Club. Inside, some of John Pule’s things as well as Mark’s litter the space. Canvases, benches, brushes, a mask fixed to one wall, old tubes of acrylic that have had the life squeezed out of them. I recognise on a table one painting not much bigger than a place-mat—a hyper-real scene of Limu Reef, Mark’s original artwork for a set of Niuean postage stamps. A corner of the painting has been repaired. I don’t think to ask whether it got damaged in the post.

There is something else he wants to show me while I’m here: the sculpture park. We get in the car and, under his direction, I drive a kilometre or two down the road into Huvalu Forest. On the right—I would have missed it—is a track and a sign: Hikulagi Eco-Park. At the end of the track, in a clearing of roughly mown grass, are a handful of sculptures, made from old timber and industrial cast-offs, the sort of structures that get added to and distort, that deteriorate and show their age. One is made almost entirely of Steinlager cans. It is an appropriate monument to the powerful presence on the island of New Zealand culture.

The Steinlagers are the work of Mikoyan Vekula, a young Niuean I met a few days earlier. With close-cropped hair, an open, generous face and dress savvy, Mikoyan appeared the embodiment of cool. But he was a coiled spring, a reservoir of undirected energy. His talk was of art and how it could change lives, revitalise cultures. Perhaps that was just the artist talking to the journalist, but with Mikoyan I didn’t think so. With some people, whatever words are used they tell the same story. It was a story I seemed to keep hearing here on the Rock.

Mikoyan was brought up in Wellington. After leaving school, he drifted through a string of jobs while suffering something of a spiritual death. He found life again through art. In 1992, he returned to Niue to look after his father. It was a difficult, unsettling time. In Mark Cross he found a kindred spirit: someone else who sees a valuable role for art on Niue.

Back at the house I look at the hiapo—Niuean tapa—that Mark’s 17-year-old daughter Koren has been working on. The New Zealand High Commission has put a grant her way to help fund an exhibition of hiapo and so encourage its revival. Rolls of imported paper mulberry lie stacked against a wall. The plant is rare on Niue, and the alternative, the bark of the ata tree, is even harder to prepare. Sometimes culture can be an uphill thing.

On a shelf I notice a bound typescript. Narratives of Encounter: The Anthropology of History on Niue. A borrowed PhD thesis.

They say nothing lasts for ever, and on Niue history itself is long gone. Old history, that is. Pre-European contact. The sinewy history of the people. Some good stories still do the rounds, but without a tradition of genealogies, getting a fix on the chronology is hard. Artefacts are even less in evidence. A visit to the national museum at the Huanaki Cultural Centre in Alofi proves the point. A modest room houses a handful of domestic ware, some clothing and a modern canoe. The best of the past is probably in European collections. This being the Pacific, much of the remainder has long since decayed.

Even I, a palagi, can see by glancing at what survives how much knowledge has been lost. In the 1880s, Niuean hiapo—which some say had been introduced from Samoa—was showing great originality. By 1901, when Percy Smith, the first New Zealand Government Resident, arrived, hiapo was already a thing of the past.

To track down an old piece of hiapo I had heard of, I stepped into the Fale Fono, the sizeable government buildings just down the road from the museum. There, in a basement office, I serendipitously came across John Funaki, the Speaker of the House. After listening to my request with wry amusement—or perhaps it was with practised patience—he showed me to the debating chamber where, behind his chair and protected by plexiglass, hung the hiapo, a delicate two-metre mandala traced in brown and black. It seemed unthinkable that so much folk memory should be embodied in something of such modest dimensions. For someone used to the archives of large museums, to whole warehouses of material culture, the thinness of the links on Niue was sobering.

Of course, I was underestimating the power of folk memory. I was also making the mistake of looking in the wrong places. The person to open my eyes to this fact was Misa Kulatea. When he isn’t home carving wood, Misa spends his days taking people on tours deep in the sacred Huvalu Forest, in what has now been declared a conservation area. He agreed one morning to take me there.

A big brawny bear of a man with a silvered mane, Misa had the smile of a gentle giant. With every twist of his body, to brush a fly or wipe sweat, his clothes stretched taut to accommodate the movement. No amount of discomfort seemed to disturb his geniality.

[sidebar-1]

We were dropped at the end of a baked-clay track off the Liku-Alofi road where open country with its scrub and talo plots gives way to a serious tangle of trees and vines. The day was just starting to get annoyed with its own heat. We watched our ride buck along the rutted ground back to the main road. Amid insect noise and bursts of bird flight, Misa hoisted a bulging backpack, swung a flask, grabbed a spade and set off barefoot across the rough moonscape of coral that formed the forest floor, into Huvalu’s shade.

In that sanctuary, surrounded by the leaves and flowers of unfamiliar trees and creepers, I was introduced to the magic box of nature: ginger, for high blood pressure; tava, a buttressed tree whose bark, made into an infusion, relieved stomach cramps; va, a climber, used as a durable binding; kanumea, a tall tree that rears through the canopy and a good place to set snares for birds and for the flying fox; le, whose fruit coconut crabs will climb 15 metres for, and whose big leaves are used for covering the umu—the earth oven still widely favoured on Niue.

Now and then, Misa would break off to fill me in on a detail of his life. Like some 400 other Niueans—over two-thirds of the adult workforce—he was employed by the government. Then, in 1990, the axe fell: the government decided to trim its proliferating public service, which, at that time, employed more than 80 per cent of the working population. Misa was out of a job.

Lacking an income, he turned to the past, learning ancient carving techniques and putting together a collection of objects he had unearthed on family land: a couple of throwing stones, a fish sinker, a stone anchor, an arrow tipped with ebony. When they move the museum to higher ground, beyond the reach of cyclone-whipped seas, he said, these things can rest there.

Two years ago, he started bush tours, sharing his knowledge of how his ancestors lived—some are buried in nearby sea caves. It is familiar country for Misa, who once hunted in the forest with his father and his grandmother, keeping the night at bay with a wood torch.

Misa explained that the soft feathers of tropicbirds, which nest high in the banyan trees, made fine fish lures. He showed me how to make fire by rubbing dry hibiscus and how to catch an uga, a coconut crab, and truss it with vines. How to make a shelter using poles and leaves, and where to plant tapioca and yams in the deep pockets of forest loam between the reef rock outcrops.

It had been a furtive life for his forebears, on an island beset by tribal skirmishes. Colonised in the north by Samoans around 1000 A.D. and by Tongans to the south half a century later, Niue also became home to Cook Island Maori arriving from the east. Settlement may have begun earlier still. Anthropologists from Canterbury Museum claim to have found sites dating back 1300 years—later, however, than the proto-Polynesian migrations to Samoa and Tonga. Whatever the exact dates, Niueans are clearly related to Tongans and Samoans in the west, rather than Tahitians in the east.

As a result of all this restless seafaring, the island was subject to prolonged warfare, though it took the form of clan bickering rather than all-out genocide; the island was spared a Pacific Attila. Paths were carved through the rainforest, which once covered most of the island, to allow warriors from the south, the Tafiti people, to harass those from the north, the Motu, and vice versa. Those such as Misa’s ancestors, who chose to dwell in the sheltering forest, learned to grow their yam crops—as many as 10,000 plants—in widely separated patches to avoid detection, and to skirt the main forest trails. The entrenched animosity was said to have ended only with the introduction of Christianity, and a legacy of those times persists in the distinctive dialects still spoken at opposite ends of the island.

Things went along in an unsettled way for countless generations, until someone arrived on Niue with a bad case of influenza or some other contagious disease. That, at least, is the conjecture, because even before Cook’s time Niueans were giving strangers the short shrift on medical grounds.

When Cook made landfall in 1774, he was ignorant of the natives’ motives and merely saw a party of locals with red-stained teeth coming at him “with the ferocity of wild boars.” The Niueans have been trying to shake off the stigma of the name Cook bestowed—Savage Island—ever since.

Seventy-five years later, when Captain Erskine paid a call, he had a rather different experience. The men, some with long plaited beards ornamented with pieces of oyster and clam shell, were peaceable. The reason wasn’t hard to find. In the intervening years God had arrived, courtesy of Polynesian missionaries.

When George Lawes, the island’s first resident missionary, stepped ashore in 1861, he told of hearing in the stillness of that first evening the sound of Christian prayer rising up from the family altars of these former savages. “Never, in the history of evangelistic efforts, has a change been wrought more marked or marvellous than in this island,” he said. And who was to argue?

The person principally credited with having brought about the change was a Samoan-trained Niuean missionary by the name of Peniamina. Two years after hitching a ride out on a Yankee whaler from Mutalau, his village in the north of Niue, he returned to convert his heathen fellows.

Unhappily for Peniamina, he fell from grace, eloping with another man’s wife. Samoan evangelists of superior character and effectiveness followed, but Peniamina had his name put to a national holiday. (After all, it wouldn’t have done to let the Samoans muscle in on the Niuean calendar, no matter what their conversion rate.)

A downside to the adoption of Christianity was that it dampened the ardour with which the Niueans repelled boarders. That made them easy prey for blackbirders, who began carting off the menfolk to work in Peruvian mines and other squalid hells throughout the Pacific.

After successive petitions to Queen Victoria for protection from other colonial powers, Niue was declared a British protectorate in 1900. The following year, while on tour in Wellington, the future King George V declared that the island had, in fact, been annexed to New Zealand—a reward (though he didn’t say it) for help in the Boer War. It was not an association the Niueans relished. And it did nothing to stem the island’s disastrous leakage of labour.

[Chapter Break]

The evening of the rainforest visit, I sprawl out on the verandah of my room, watching the sun dip below the pawpaws and listening to the murmur of hens as they pull flesh off split coconuts on the lawn. Beyond the cliff, seawater drains from Avaiki Cave, by tradition the site of the first canoe landing.

Loma Mitihepi, my host in Makefu, walks up with his limping gait—the legacy of a 20-year-old motorcycle accident—and eases himself into the chair opposite. I’m in distinguished company. Not only is Loma secretary and head deacon of the local church, he is also chair of the Tourist Authority and acting Minister of Tourism, Finance, Justice and Small Business. It’s the sort of thing that happens in the world’s smallest state.

He is also a former principal of Niue High School, with 14 years’ service at the desk. The school, which follows New Zealand curricula, offers study to sixth-form level. Students keen on tertiary study have little option but to head for New Zealand.

After deciding that the pawpaw in the fridge will keep and that the plantains are holding out, Loma and I begin chewing over the vexed question of individual land titling, a process begun in 1969. Loma—who has also served as a land court commissioner—is all in favour. Titling will allow development and give women the same rights as men to family land, he says. Those opposing it are strong in the community and don’t want other relatives to enjoy their rights.

Niueans are among the most individualistic of all Pacific peoples. I’ve read that in books, and, having spent time here, I have come to agree. With no strong tradition of chieftainship or religious hierarchy, they have developed a profoundly democratic form of central and local government. Who else would elect a premier with a show of hands? Where else would you get 90 per cent voter turnout at a general election? But voluntarily start a fishing cooperative? Not likely.

The rugged strain of Niuean individualism shows up even in sport. Loma remembers the pre-cricket association days, when every village had its own rules, and games on the village green often ended in turmoil: “If, half way through, things weren’t going well for the home side, the rules would change.” He stifles a grin. “The pride of some villages could be damaging.”

Nosing about the island, I often came across kids playing cricket on the village greens under electric lights—fed, like all things electric, by the diesel generators in Alofi—while dinners were readied in the umu. On Saturdays, the villages grow quiet as people head up into bush gardens, sometimes kilometres off, to tend talo. Often setting out before dawn, they may return home for breakfast, but in the afternoon will work again until sunset.

Life hasn’t always flowed so easily. Under a succession of inept or tyrannical resident commissioners, Niue felt the heel of New Zealand rule for three-quarters of a century. One particularly severe martinet, Hector Larsen, found it expedient to introduce curfew laws giving him the power to confine Niueans to their houses after 7 P.M.

Under his authority a person could be sentenced to 90 days’ hard labour for possessing a bottle of yeast—the buying or brewing of alcohol was forbidden. Even the Polynesian tradition of carrying gifts, mainly fresh foodstuffs, seemed to be attacked by arbitrarily enforced customs regulations at the wharf.

On August 14, 1953, the accumulated anger and frustration of generations burst its fetters. Larsen was killed in his bed by three prisoners wielding machetes, and the lid was lifted on New Zealand’s colonial excesses.

I ask Loma how he feels about the drift of young people to New Zealand. He draws a breath, as if the question needs bracing against. “Our dual citizenship is a problem,” he says. “If a person doesn’t like it here they can go to Auckland and live off the dole or get a job. They may come back with good clothes and money, maybe a car. But a car can fall apart in two years.

“We have a saying: ‘If you can’t plant in Niue, how can you plant in New Zealand?’ In other words, if you can’t save money or whatever here, how will you be okay anywhere else?”

The humour which has played on his face during our conversation drains away. He looks at me intently. “If I have the money I will travel the world, but I will never leave Niue,” he says. “This is my life.”

[Chapter Break]

Not long after settling into my room I noticed an advertisement taped to a nearby window. It mentioned the Matavai Resort. “If you are on earth, this is the only place to be on Friday nights,” said the sheet. Eighteen dollars. Barbecue. Live music.

Since then, I have been to the resort, a flash new 48-bed conference centre and tourist showpiece on a broad sweep of coast to the south. Fringed with palms and fitted out with swimming pools and a generous splay of decks, Matavai Resort is typical South Seas—without the sandy beach. Instead, there is a booming coral-studded coast and a taste of raw Pacific.

Driven to the Matavai by hunger—some nights the rest of Niue just decides not to play the tourist game—I cut my way through wahoo fillets poached in white wine with dalmonico potatoes, creamed cabbage and talo in an almost deserted restaurant. In the foyer, a massive canvas by Mark Cross hung impassively, a gecko’s tiny foot poking out from behind the frame. Outside, the sea thundered. Fronds stirred. The television at the bar told of a prison standoff in New Zealand, with inmates holding guards hostage. Of political bickering and social violence. It seemed a bulletin from hell.

Returning home along the deserted coastal road, I turned off the car headlights for a moment, dispensing with the mechanical brilliance of my passage to find out what the night was really like. What it was—thanks partly to the low cloud—was a pitch blackness so intense that not even the nearby leaves could be seen. With the lights back on, I could again see here and there a long-legged land crab, a kalavi, on its way to the sea to breed.

A week later, I am unexpectedly back at the Matavai. An open-slather 10-dollar-ahead eat-what-you-can bash is on offer as a warm-up to Niue’s annual Constitution Day celebrations—and perhaps in the hope of getting something through the tills of this 51 per cent government-owned piece of real estate.

Most of the island, it seems, has risen to the challenge. Amid the bubble of talk, the clatter of plates and the frequent shrieks of laughter, I notice a lot of familiar faces. Beverages flow. The sea continues to do its rhythmic magic against the coral. And down by one of the pools, Island Pride, a five-piece Mormon combo in snazzy matching jackets, starts dishing out the goods. Baby come back . . .

Partway through the evening I catch sight of Premier Frank Lui at one of the upper tables, and engineer an introduction. Taking his ease in a short-sleeved shirt, and surrounded by the debris of a meal, he rises affably. His eyes are framed with the creases etched by a lifetime of good humour. I explain the purpose of my visit, and he becomes animated in praise of Niue. Abandoning a smouldering cigar in favour of a cigarette, he tells me tourism is a priority for his government.

At present, some 2000 people per year visit Niue, pumping more than $1.5 million into the island economy. Premier Lui feels sure Niue could handle ten times that number of tourists, given that similarly-sized Norfolk Island manages 30,000. More infrastructure is needed, he agrees, and more flights, but development should be at a pace Niue determines. It must be gradual. Already Hanan International Airport has been given a $6 million extension to accommodate B767s, although ongoing difficulties over pricing and flight frequencies—the sole carrier, Royal Tongan Airlines, makes only two appearances a week—are affecting visitor numbers.

Premier Lui, who once earned 2/6 a day working for the transport department, is keen on do-it-yourself enterprise. He would like to see the country become less dependent on aid dollars and stocked with individuals ready to help themselves.

He is lobbying for portable superannuation to be raised from 50 per cent to 100 per cent, to attract retired people back home from New Zealand. If they come back, he reasons, their offspring will follow. The empty houses they return to will need new toilets and showers. There will be work for plumbers and labourers.

The government has indeed had some success in encouraging private enterprise in recent years, with a sharp rise in the number of registered businesses and a doubling of the number employed in the private sector since 1994.

I mull over some of Niue’s ingenious attempts to further improve its economic prospects, among them the trialling of vanilla as an export crop, the building of a quarantine station for Peruvian alpaca en route to Australia, plantation forestry, the leasing of four-digit telephone numbers to international clients. But inventiveness is no guarantee of economic stability. After all, the island once exported woven hats to New Zealand and elsewhere—as many as 30,000 a year at the turn of the century—along with hand-sewn rugby balls. The real problems are the persistent ones: uncertain and infrequent transport links and the continuing depopulation.

An indication of the vulnerability of Niue’s income is shown by the 40 per cent slump in exports to $317,000 which occurred in 1996, largely as a result of a drought affecting the talo harvest. Talo accounts for 85 per cent of all exports. In the same year, imports reached a five-year high of $5 million.

By now the sky is a dark veil shot with stars and the nearby coconut palms have been reduced to intricate rustling silhouettes.

Premier Lui has a final observation to make. Niue, he tells me, grows the best coconuts in the Pacific. And the best talo. I recall that, almost 100 years ago, the dispassionate Percy Smith said exactly the same thing.

[Chapter Break]

The Week Before I arrived in Niue an unfortunate thing happened. Down at the Pacific Way bar, owner Ken Viviani ran out of the raw materials for his Fiafia lager. Elsewhere, grocery shelves emptied of biscuits, sugar and flour. And up in Tuapa village Reverend Taoa Folekene sat fretting over the absence of necessities for his daughters’ ear-piercing ceremony. The delay of a freighter meant the usual monthly restock of the island had not taken place. The ear-piercing had already been set back once when ordered goods failed to arrive. Some families discovered on that occasion that their long-awaited goods had been offloaded in the Cook Islands.

Then one Sunday, two or three weeks late, the ship slipped in, its cargo painstakingly transferred by lighter to the derrick on Sir Robert’s Wharf (named after the former premier, Sir Robert Rex). Alofi’s shelves filled once more, and a relieved Reverend Taoa announced to the world that his daughters’ ceremony would go ahead.

In a hall decorated for the event and warmed by friends and family, Taoa and his wife Manogi steered their garlanded children lovingly through the web of tradition that is a Niuean ear-piercing. Terrisha and Corrina, 16-year-old twins, choked back their emotions as they gave thanks for their family, for the shelter of their parents’ care. The hands of their brother David trembled as he took the needle-thin lime thorn and pressed it through the soft skin.

More speeches followed. Cards were read out: Best wishes to Risha and Rina from “the homies in Auckland,” from “the tribe in Avondale.” A pair of earrings from palagi friends in Oamaru were uncased.

While a plugged-in dude calling himself Blackbush Discotech cranked up Puff Daddy and Hanson, the reverend proudly stepped out to strut his stuff with his daughters and Manogi scattered sweets among gleeful children.

Outside, on a makeshift scaffold, helpers had started chopping their way through some of the 34 pig carcasses for distribution to the guests. On the grass stood long rows of bound talo and baskets for the cleaved meat.

I asked David how it felt to be here in Niue after such a long absence. An employee of Fletcher Steel since leaving at the age of 19, he had never been home.

“Everything looks smaller,” he said. “It’s too hot. I have to swim three times a day.” His eyes betrayed a longing. After a silence, he added: “There is no job to come back to. If I won the Lotto, I’d be here.”

Days later, at the airport, I catch sight of David again, with his wife and children. It is plane day, and the foyer is crowded. Even people with no intention of flying and no one to say goodbye to are there, just to see what’s what. Ahi appears and drapes a necklace of bright yellow shells around my neck in farewell. At the weigh-in, a bag of coconuts is being sealed with official tape. Taoa and Manogi look across and wave. They give their son a parting hug. Then everything becomes a swirl of movement.

As the plane rears up, pushing David and his family and me back against our seats, I think of Fai down there, bright against the sea, of Loma piercing the coral to plant talo. Of Misa out among the medicine trees of his sacred forest. We bank for Auckland, pitching the horizon, pushing Niue back until it is no more than a thumbprint on the plain of the Pacific, and I wonder at the resilience of the human heart. At the way laughter wins out, and how hope can stay alive even among rocks.