Life and death among the nettles

Whether dancing above a flower or alighting to sip nectar, New Zealand’s two species of admiral butterflies are a delight to watch. But other eyes watch to devour these splendid creatures, and more often than not the battle for survival goes against them. The brown soldier bug targets the caterpillars, which feed exclusively on nettle plants.

It all began in the spring of 1993. After five-and-a-half months in Greenlane Hospital I was home again, weak after major heart surgery, broke after two years off work but itching to get out the camera and start photographing again.

For a dozen years, I had spent every spare moment chasing birds with my camera, including making three trips to north-western Australia to photograph there. Although bird photography was my main passion, all facets of nature, from frogs to flowers, fascinated me. But I never expected much from nettles.

Our quarter-acre section in the Bay of Plenty is a tangle of shrubs, trees, vegetables, cacti, bulbs, perennials and more, accumulated by my wife and me over decades. As we do not believe in spraying our plants, the garden is infested with just about every conceivable variety of crawling and flying insect to be found in this corner of the globe.

Hidden behind the garage is a patch of the introduced nettle Urtica dioica, originally planted by my wife for its leaves, from which she occasionally brews nettle tea. For years I had cursed its irritating foliage, but now I decided to start photographing its inhabitants, for this pestiferous plant hosts some of our most beautiful insects, the large and splendid admiral butterflies.

New Zealand’s butterfly fauna has always been considered rather impoverished. While Australia boasts 396 species and rising, until recently we could muster only a miserable 13 endemic species, with another dozen or so recorded as windblown visitors.

Re-examination of butterfly taxonomy over the past few years has lifted the potential tally considerably. The widespread common copper butterfly, for example, may consist of up to 25 localised species or subspecies, and other cryptic butterfly species are probably still to be unmasked.

Two of our most attractive mainland butterfly species are the admirals: the red Bassaris gonerilla, New Zealand’s largest endemic butterfly (wingspan 60 mm), and the yellow Bassaris itea (wingspan 50 mm), which is also found in Australia, Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island, the Loyalty Islands and on the Kermadecs. Both species range throughout the country, but are more common in the South Island.

The Chatham Islands has its own subspecies, the Chatham Island red admiral, Bassaris gonerilla ida.

Five species of admirals are also found in Europe, Asia and North America, and although they are classified in a different genusVanessa—they are quite closely related to our admirals

Red and yellow admirals take their names from the colour of blotches on the upper side of their wings. The undersides of the wings are cryptic in colour—very different from the gaudy topsides—and, as they normally rest with folded wings, the butterflies are often difficult to spot. Opening the wings to reveal the large bright spots is thought to be a ploy to confound a potential predator, allowing the butterfly to make its escape.

All the admirals are strong, rapid flyers. Yellows are considered to have flown or been blown here from Australia in relatively recent—although still pre-European—times. Once here, the species dispersed slowly, and didn’t reach Southland until the 1970s.

Yellow admirals are more commonly seen in gardens than are their red cousins, which are encountered more in forest and alpine areas. Fermenting sap seeping from wounds on the trunks of beech trees seems to attract red admirals, and from time to time they may be glimpsed sipping this liquor.

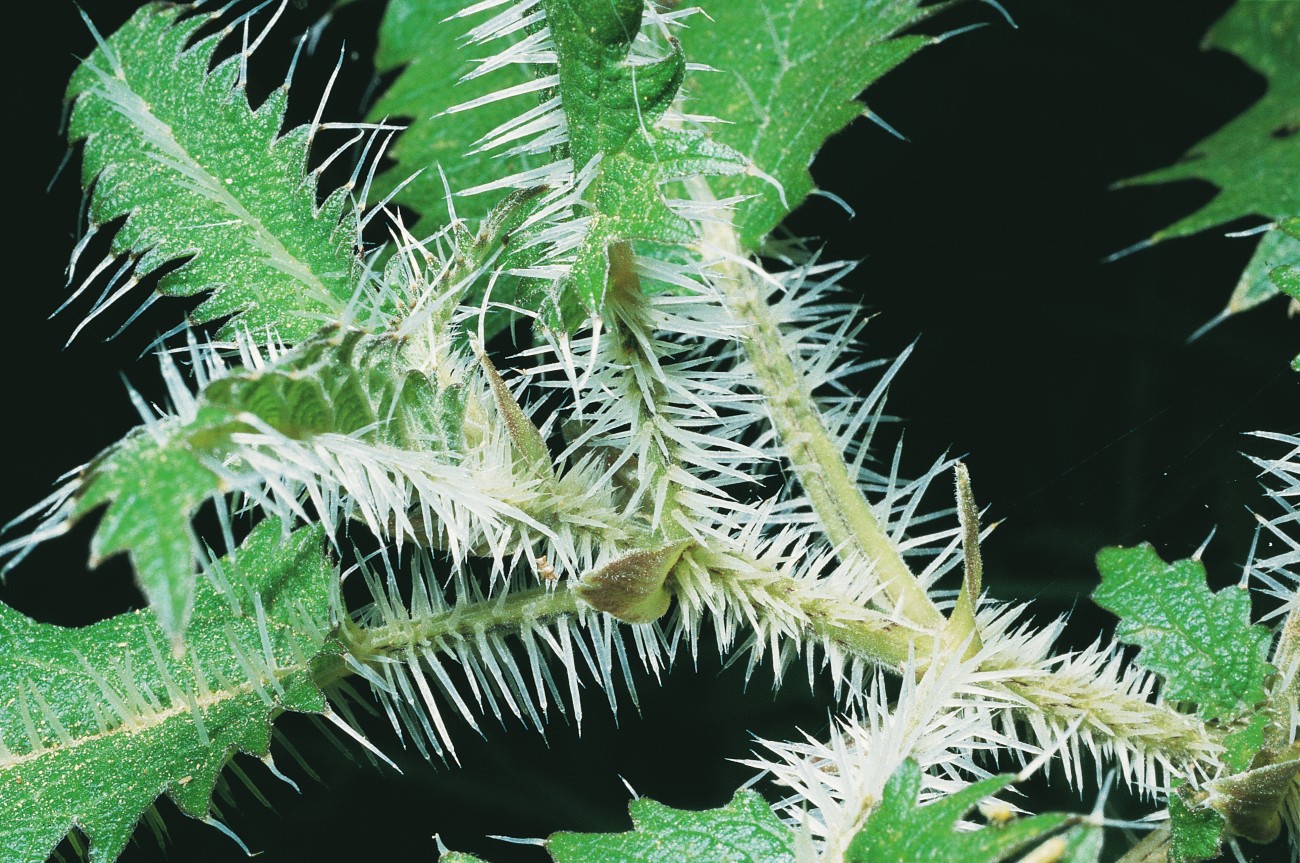

Prior to the introduction of nettles from overseas, the caterpillars of all three admirals dined exclusively on the five species of native stinging nettle. Red admiral larvae still favour the savage tree nettle or ongaonga, Urtica ferox, seemingly oblivious to its vicious spines. Yellow admiral larvae seem to prefer the herbaceous Urtica incisa. Introduced nettles now supplement the native species in the diet of the caterpillars, especially yellow admirals. Neither species seems troubled by the plants’ spines and toxins (see sidebar, page 62).

Judging by their own epidermal coiffure of bristles and spikes, the caterpillars look to be right at home.

[Chapter break]

In winter, the nettle plants in my garden die right back, not resuming growth until early spring. Like monarchs, a few admiral butterflies survive the winter months, typically hiding within dry foliage, often in the bush, and emerging only briefly on warm days. From the tattiness of the wings of many admirals-even during the summer-it is thought that the butterflies are quite long-lived, probably surviving for several months, while those that overwinter may live for six months.

In spring, the matriarchs lay tiny translucent eggs (opposite page) in the new growth of the nettles. Eight or rune days later, the tiny larvae escape from the egg via a small hole they chew in the top.

By November, the rapidly growing caterpillars have chewed chunks from many leaves. Some leaves, secured by silk threads spun by the caterpillars, have been folded to form shady retreats in which the insects pass many of their daylight hours. Although such seclusion offers protection from birds, the larvae are not inactive in their “tents,” for they reach out and seize surrounding leaves. Caterpillars tend to make a succession of these shelters during their four- to six week larval lives, as they quickly run out of leaves within reach.

By February, the nettles are eaten down to ragged skeletons, still patrolled by fat, dark caterpillars seeking those last fragments of leaf.

At least that is the ideal. In fact, in the nettle patch the caterpillars come under attack from every direction, and in the past decade their situation has become even worse. Hunting spiders are never averse to a feed of caterpillar. Birds take some, although I have rarely seen this happening. The brown soldier bug, Cermatulus nasalis, impales both caterpillars and pupae with its long proboscis and sucks out their juices. Australian paper wasps and German wasps take some, but the worst offender is the Asian paper wasp (see New Zealand Geographic o. 26), which has only become thoroughly established in this decade. Their nests are everywhere around the garden, and they decimate all caterpillars, which is great for cabbage and cauliflower crops-even for the nettles-but murder on butterflies.

To give the admirals more of a chance to survive-and myself a better chance of photographing them-I decided to bring the caterpillars inside. Soon the dining room table was covered with pots of nettle, and caterpillar droppings littered the tabletop. It is as well that my wife is also fond of nature-such items are not eve!)’ housewife’s ideal in table decoration. As we sat at the table eating our meals, we could watch our charges eating theirs.

[Chapter Break]

When they reach maturity, the caterpillars wander about in search of a suitable site for pupating. Outdoors, this is usually the solid nettle stem, but they may choose another type of shrub nearby, or attach to a structure such as a fence.

Indoors, stems are still popular, but caterpillars can turn up just about anywhere. I found 15 chrysalises hanging under the dining room table, hidden behind the tablecloth. Once in place, the caterpillar will hang for 24 hours or longer. Clasping the stem with its rearmost pair of feet, head curled under, it awaits the developments that will see it transformed from a bristly caterpillar to a smooth chrysalis.

At the onset of transformation, the suspended caterpillar begins to shudder and stretch. A split appears in the skin on the back just behind the head. Gradually the split extends and the old skin peels back. The emerging pupa seems to simply contract slightly in length and at the same time swell up to burst its way out of the old skin. Due to the tapered shape of the pupa—thickest at the head end, slimming towards the attachment point—the skin peels upwards. When it seems that the job is all but done, the pupa begins to squirm frantically until its old skin is just a thin rolled-up stocking encircling the stalk, which now supports the chrysalis.

Newly emerged, the pupa is a fresh and shiny grey-green. Where a double row of bristles once ran along the back of the caterpillar, orange tubercles now stand. The past life of constant activity and eating has given way to quiescence. The caterpillar is dead; long live the pupa! Yet even now the wing outlines of the future butterfly are clearly discernible on the newly-minted chrysalis.

[sidebar-1]

How long the insect spends within the pupal stage depends upon temperature, but between 14 and 18 days is an average incarceration in summer.

Even before I brought caterpillars into the house, I had brought in pupae, mainly because I was keen to capture on film the moment when a butterfly emerged from its chrysalis. To my astonishment, it was no beautiful admiral that materialised from the first pupa to “hatch.” In its stead a procession of 3 mm black flying insects swarmed out. These proved to be Pteromalus puparum, a parasite introduced in 1933 to control white butterfly. Sadly, this early example of biological control had some regrettable side effects, for the parasite has seriously depleted populations of both red and yellow admiral.

Time and again, the pupae produced the same teeming numbers of these parasites. Other chrysalises, coloured a beautiful coppery colour, proved no less disturbing. From each sprang a startling black-and-orange ichneumon wasp with white spots, Echthromorpha intricatoria. This Australian species, first recorded here in 1915, appears to have had a severe impact on the admiral population. A 1937 report from Wanganui noted that more than two-thirds of red admiral pupae were parasitised by this wasp. Forty years later, 94 per cent of 194 red admiral pupae located in the Orongorongo Valley in southern Wairarapa were found to be infested, and even at an elevation of 700 metres, 80 per cent of pupae were parasitised.

The wasp uses its long, needle‑like ovipositor to inject a single egg into a wriggling but defenceless admiral pupa. The alien takes about two weeks longer to develop than the butterfly it consumes.

[Chapter Break]

Admiral butterflies did emerge from a few chrysalises, but it was several years before I was able to capture the critical moments on film. The problem was that my wife and I could never tell exactly when a butterfly was about to break out, and the event was over in two minutes. We could be sitting at the table with a row of quiescent pupae in front of us, and moments later there was a fully formed butterfly hanging from one of them—and it was never the one the camera was set up on.

Eventually, I secured sequences of photographs showing the emergence of several yellow admirals, and one red admiral. The usual time when they made their move was from mid-morning onwards. A split appeared on the back of the chrysalis near the head, and it rapidly enlarged as the still-folded wings pushed outwards. Once out of its enveloping skin, the insect turned 180 degrees so that its head faced upwards. The downward-hanging crumpled wings were rapidly pumped up (by the passage of fluid through the wing veins), and in less than five minutes all that held the butterfly back from flight was waiting for its wings to dry.

Last summer we released 20 or 30 admirals back into the garden after raising them inside. No more than one or two of the caterpillars we left outside survived the gauntlet of predators and parasites.

We delighted in watching “our admirals” flit around our plants before heading off to explore the world. Perhaps we’ll see their offspring on the nettles next season.