Let the taiaha be a vessel

Almost every year since 1973, tāne Māori of all ages have travelled to an uninhabited island in Lake Rotorua to train in the traditional art of taiaha. They learn how to hold an ahae, or defensive posture, how to perform a poua, or strike, and how to lay down a wero, or ceremonial challenge. But there’s something deeper in play: the wānanga connects modern people to old knowledge, and to each other, and that changes them. It’s become a place of second chances.

There were only two other students in the te reo class at Dilworth School in Auckland. When I turned up, one of them told me about an ancient wānanga held at Mokoia Island. Each year, he said, a select few rangatahi and tāne were invited to the island to learn the art of Māori weaponry.

“Everyone that goes there is mean,” he said.

As a teenager, I envisioned fit young warriors learning taiaha from tohunga. Sitting around a big fire sharing stories of the past. Boys becoming men and men becoming warriors.

For a moment, it seemed we might get the chance to attend this wānanga. Our reo teacher got in contact with the organisers; there was talk of the three of us heading to the island later that year. We were all eager, but I was particularly excited. A deep desire was lit within me. I can’t remember why we didn’t make it. But as time went on, as I got older, that Mokoia flame dimmed.

[Chapter Break]

“Kia ora, bro.” Te Rawhitiroa Bosch leans over. We hongi, exchanging the breath of life. We’re in McDonald’s Rotorua—it’s seen a few hongi, I guess. Te Rawhitiroa, a proud Ngāpuhi and the photographer for this story, has been coming to this wānanga since he was a boy. Now he’s one of the organisers who days ago, with a major storm forecast, made the tough call to shift this year’s wānanga from Mokoia Island to Tarimano Marae, on the lake’s edge.

“Should we stop and buy a broom?” I ask as Te Rawhitiroa drives us out of town.

“Nah, all good, bro, I’ve brought you something to use. It’s got a bit more mana than a broomstick.”

We stop off at Pat Mohi’s place. He’s the son of Mita Mohi, the founder of this wānanga. He pulls me forward for a hongi, and explains how the wānanga evolved.

It’s difficult to pin down precise dates and numbers, but the story is what matters here, and it’s one of vision and change. “When my father was taught, there were only three students at a time,” Pat explains. “It was only for Te Arawa, specifically those from around here.”

By about 1980 the wānanga was held on Mokoia Island and the doors had been thrown open: all Māori men and boys were welcome, regardless of affiliation. And they came in their hundreds. There were four wānanga each year, with more than 300 boys attending each one. Mita, who worked for the then Department of Māori Affairs, also started bringing the wānanga to Māori who were incarcerated.

A kaumātua for the New Zealand Police, a member of the Parole Board and a justice of the peace, he saw too many Māori men and boys struggling to see their culture as a positive. He knew taiaha was a tool that could forge a new kind of connection, Pat says.

Mita was made a member of the Order of the British Empire in 1995 and his death, in 2016, made headlines nationwide. The New Zealand Herald reported that in a speech at the tangi, actor Cliff Curtis credited Mita and the wānanga with saving his life. He was sent to Mokoia as a 12-year-old ward of the state. “Life was not going well for me at the time, I was a problem child… He gave me hope and purpose and faith… but he didn’t just do it for me… he changed tens of thousands of lives for the better.”

Over its 50-year span, more than 20,000 men have experienced the wānanga—and with it a new way of connecting with their culture. The wānanga has evolved over time, as have the needs of the people it serves, yet it remains based on the kauae runga, or spiritual knowledge of the heavens.

This year’s venue, Tarimano Marae, was where the wānanga began, Pat points out. And that’s where his father learned taiaha. It’s fitting that for this 50th anniversary, the wānanga should return here.

Down the road at the marae, a dozen or so men have shown up a day early to help organise things. Te Rawhitiroa reunites with what seem like long-lost brothers. “My bro! Great to see you, how you been? How’s so-and-so?” After the initial intro, I duck across the road and light up a rollie behind a ute to calm my nerves. In the fading light I make out a pou, standing in the bush right in front of me.

A karanga rings out to mark the transition from Te Kore to Te Pō to Te Ao Marama, from the domain of Tū to that of Rongo. I raise my head to acknowledge the tekoteko of the whare. The tupuna is holding a taiaha.

Inside, the whare is filled with intricate carvings depicting significant tupuna and the walls are adorned with photographs of loved ones who have passed on. I have always loved whare like this. We don’t have many like them in the North.

The men sit, and with Pat presiding, we all formally introduce ourselves: “Tūhoe! Ngāpuhi! Te Whānau-ā-Apanui!”

[Chapter Break]

Next morning, the wharekai and marae ātea are full of life: it’s drop-off day for roughly 150 boys and teens. They and their families are a mix of nervousness and excitement. After the pōhiri, we’re split into four groups, ranging from under-sevens to adults. Some of the young boys and teens are already old hands here. These young veterans make up a fifth group: they’re junior tutors.

“Are you scared?” one young boy asks another.

“I’m not scared,” he replies.

“Me neither. We’re not fighting, we’re just practising for when the day comes.”

Listening, I remember being excited about this wānanga as a child. I think about the kind of role model I am and the type of father I hope to be some day, this chance to prepare for the challenges that lie ahead in my own life.

Before any of us picks up a taiaha, the entire wānanga makes the 20-minute hikoi to Puhirua, te urupā o Ngāti Rangiwewehi Awahou. Among the headstones, the group gathers around the grave of Mita Mohi and his wife, Hukarere—or Koro Mita and Nanny Huka, as they were widely known. Some of Mita’s grandsons explain how special it is to be able to take the wānanga to Mita—this has not happened since he passed away six years ago.

They share kōrero about the significance of the site, and Mokoia. In idle moments during the weekend, I find myself staring at the island. Sometimes it seems to be staring right back.

Once prized for its defensive capabilities and fertile soil—said to be the only place in the area where kūmara grew well—Mokoia is at the heart of a famous love story, in which Hinemoa swims to her lover Tūtānekai. But there are many other stories.

Pat’s son Herora Mohi explains that the island was once called Te Motutapu-a-Tinirau. That name was given by Te Arawa ancestor Īhenga, a famed discoverer and claimer of land. The island reminded him of his ancestor Tinirau, a man who could commune with whales, and lived on a sacred island back in Hawaikii.

There are several accounts of how Mokoia got its current name. One involves a flock of birds taking off with a fishing net, another, a blow struck with a kō, or digging stick. There’s also kōrero about how the island was renamed in honour of a deeply missed wife. Each retelling keeps the flame of memories and history alive.

Throughout these kōrero, the rain drizzles down in approval.

[Chapter Break]

That night, my roster group, the Crazy Horses, is on dishes. A dozen or so men, mostly teenagers, whizz around the kitchen stacking plates and sorting cutlery. One table remains standing in the wharekai, filled with older men laughing as they lean back, patting their bellies in content. Troy Harbottle, a carver, is drying the last of the dishes. I search for the driest tea towel and join him.

“This is my favourite part of the wānanga,” he says. “Talking with people.”

The talk is different here, I’ve noticed. More open, more meaningful.

Later that night, in the smokers’ section over the fence, I realise that a couple of the others are from Whangaparāoa, like me. One of the younger guys, Te Amorangi (Dylan) Brown, is wearing a Silverdale Seahawks jersey. He’s large and fair-skinned, with a tatau on his right shoulder.

“You still play for them, bro?” I ask, pointing at his shirt.

“Nah, not any more,” he says.

“I grew up there. Used to play for the Seahawks back in the day,” I tell him.

Just like that: connection. Dylan’s just turned 20; this is his first time at the wānanga but his brother Maatua Hirumana-Rua has been coming since he was a young teen. The two explain that Maatua’s family would take Dylan in whenever his mum kicked him out. They talk about Dylan dropping out of school, being shunted between foster homes, and how he came out thinking his mother doesn’t love him.

“This wānanga, the way people talk here, it’s so open and so real. It’s like we’re all mates and we can just be ourselves,” Dylan says.

Back inside, the group take turns introducing ourselves. Peet Van Dijk has been coming to this wānanga for 20 years. For the past 10 years, his friend Hans Lantinga has travelled from the Netherlands to attend, too. They are both covered in moko, including pūhoro—a tattoo that captures the essence of the wearer’s whakapapa—on their thighs.

A few men are returning for the first time since they were children; they’re here now with their sons. One koro is here with six mokopuna in tow. I think about what Pat said: taiaha not as weapon, but vessel.

[Chapter Break]

To start day two we zig-zag through the bush and around the awa to reach the sacred spot commonly known as Taniwha Spring. More than three million cubic litres of water spring forth from this puna every day and it is crystal clear.

Ngāti Rangiwehiwehi believe this spring is protected by one of their kaitiaki, Pekehāua. The taniwha’s tail is said to have carved the Awahou River, which runs alongside the spring and is connected by underground passages. No one drowns in this river—or so the kōrero goes—and Herora explains that’s because of Pekehāua.

No one drowns, but the history of the site is fraught. According to a report commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal in 1991, the Crown took the land around this spring in 1966, citing the Public Works Act. The nearby township of Ngongotahā was growing and needed more water. So the Crown cleared areas of forest, made a road, installed a pump—and for some 50 years the spring’s healing water was pulled away from the river.

The water was once abundant in watercress, kōura, and trout, but by 1991, the level had dropped and only a few trout remained.In 2015, Rotorua Lakes Council voted unanimously to transfer ownership of the taonga back to Ngāti Rangiwehiwehi. Today, Pat’s sons invite us to fill our drink bottles.

I press my hand to a cabbage tree, and recite a karakia.

“Io e, e Io e, tukuna mai.”

[Chapter Break]

Back at the marae, in the drizzle, we break off into our groups. Our tutors today are Maatua Hirumana-Rua, one of the young men from Whangaparāoa, and Kaea Haerewa (Tainui, Te Arawa, Ngāti Porou). They’re guided by two elders in the group, Larn Wilkinson (Tainui) and Matiu Tahi (Tūhoe).

Taiaha time at last. I’m excited, and nervous as. The rākau Te Rawhitiroa has brought for me is a koikoi, a long stick with two pointed ends—and it does have some mana, but it’s about two feet too tall. Kaea notices. “It’d be good if you were Te Rawhitiroa’s height. Let me find one that’s right for you, eh bro?” He marks my chin height on the koikoi.

Returning, he hands me what looks like a broom handle. “Thanks, bro, know what it is?” I ask.

“I think that there’s just a bit of oak,” Kaea replies. He’s too nice to point out the obvious.

The tutors start with the basics, demonstrating each stance, block, strike, and parry: “Hawaiki tū! Mangōpare! Mangōpae!”

As I start to move and turn with the rākau, I feel the rust and apprehension fading away. My body remembers that it learned some of these moves long ago.

Later, we stand on the bank of the river, the air thick and warm, as each group showcase what they’ve learned. The young ones are ahead of us, and it brings us immense joy to see them thriving.

After dinner, Te Rawhitiroa calls me out the back of the wharekai, where around a dozen men are seated, sharing laughter and kōrero. I quickly click that this is effectively the council of the wānanga. These men carry the mauri of the kaupapa, the rangatira, tohunga, and toa of Te Wānanga Mau Taiaha o Mokoia. This is their daily debrief and planning session; I am happy to listen and learn, a manu on a perch.

Each night there is also a wider korero involving the whole wānanga. On the island, the boys would have a famous Mokoia Milky Milo (the secret ingredient is milk powder), wrap up in blankets, arrange themselves on ‘The Rock’—which looks like Pride Rock on The Lion King—and listen to the older men share their stories. The young ones fall asleep under the stars near the fire, and are carried to bed after the final karakia. Tonight, the wharenui is our rock and I feel like a young boy again, hui-hopping with my father and drifting off to sleep listening to the elders speak late into the night.

We learn about the duality of man and the presence of Tūmatauenga and Rongo within each of us—war and peace, how they fight every day, and how we call upon these atua at different times in our lives.

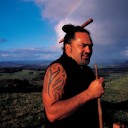

These men around me are at the top of their fields: military personnel, entrepreneurs, carvers, animators, environmentalists, iwi governance members. They care for their whānau, hold down jobs, chase their dreams, support their communities and practise their culture. They’re warriors: the opposite of the Māori gangsters we’re so used to seeing on our screens.

[Chapter Break]

Early next morning, a blanket of grey hangs over the lake. Mokoia Island is hazy, the humidity rising with the sun. I catch distant chatter from the teachers in the kōhanga next door. Herora and I sit on the back deck, sipping black coffee.

“Seen that Vegas TV show, bro?” I ask. The show was filmed in Rotorua and tells the story of Māori gangsters planning one last meth cook before going clean and buying back ancestral land.

“Yeah, bro,” he says, as he has another drag from his vape, looking at the ground.

“Pretty shitty depiction of the place and our people, eh?” I say as I puff my Port Royal.

The rain is heavier and so is my body. We gather on the ātea, the open area in front of the wharenui—the domain of Tūmatauenga, god of war. We practise what we learned yesterday, but on slippery wet concrete I am hesitant to give it my all. I bang my knee too hard dropping down for a move. Shifting to the grass, I do my best to keep up.

Matiu Tahi has taken over tutoring today.

“At my marae in Tūhoe, they call me the stickman,” he says. The stickman is in a camo jacket and red Nike shorts. He has white hair down to his shoulders and a slight lazy eye, adding to his overall mean Tūhoe demeanour.

“There’s that shoe company with that saying, ‘just something…’,” says Matiu, baiting a response.

“Just do it,” snaps one of the boys. “That’s it! Just do it. Well, don’t just do it, be it. Don’t just do taiaha, be a taiaha warrior…

“Bleeeeh!” Matiu performs a pūkana.

“When I go into a fight, I don’t fight to lose. It’s my ass or theirs and I can tell you, I’m not losing.

“Hit me,” Matiu says to me. I’m afraid I might dong the old fulla on the head. My downward strike veers left. Matiu is laughing, yelling this time: “Hit me!”

I aim right for his head and he slides out of the way, countering before I have a chance to realise what is going on. “See, that’s how you do it,” he tells the class.

We begin learning the basics of a wero—the challenge delivered during pōhiri. We form a semicircle and take turns. A few of the boys have a go before I finally build up the courage myself. I walk to the far end and turn to see the group facing me. I place my rākau on the ground, and begin reciting my karakia. From there, my actions feel automatic. As I lay the take—a small piece of greenery, a ceremonial token of challenge—for the first time, I start to dream about performing a wero at my own marae, Manukau in Herekino. I think about bringing my cousins and nephews here to learn how to do it, too.

“Remember,” says Matiu, “when you come here, you carry the mana of your hapū, the mana of your iwi. Wherever you go, whenever you use a taiaha, you carry that mana and responsibility.”

This guy is the Tūhoe Yoda.

Our feet begin to flick more in unison; the grass underneath turns to mud. My calves and quadriceps burn. Puffing, exhausted, wet, I try to hold on to Matiu’s edict. I try to carry the mana of my people.

Someone shouts in pain.

Dylan has hit the deck, grimacing. The group naturally encircle him as Larn tends to the injured leg. There’s a powerful feeling of brotherhood in the air.

[Chapter Break]

“Hā ki roto.” I close my eyes and take a deep breath in.

“Hā ki waho. That’s us, my bros.”

I breathe out and open my eyes, ready to explode. “Kia mau! Hii!”

The air in the wharenui, where we’re learning haka, is moist and warm. There’s a big fan up front but three rows back you can hardly feel the breeze. Over and over we perform that haka, maybe 20 times in the space of an hour, yet I’m still unsure of the actions and words.

By the next morning, our minds are on the whānau performance happening tomorrow. At dinner time, after another day of training, and a visit to pay our respects at nearby Waiteti Marae, I slip away across the road for a soak in the awa by myself. There is not much light left. I immerse myself in the freezing water until my knee starts going numb. I almost didn’t make this trip. I was feeling burned out and had a lot going on. I’m grateful that my partner persuaded me to go, and can’t wait for the next one. I karakia, giving thanks to the sacred waters of Pekehāua for its healing and strength. My body feels reset and I am reinvigorated, ready to go.

Later, the group gathers inside the wharenui. This final evening feels likes a festival. Each region performs—not as a competition, or a chance to show off, but as an acknowledgement of the haukāinga and organisers. It’s another reminder of the mana gathered for this wānanga, from Te Wai Pounamu to Te Hiku o Te Ika.

I sit outside with Matiu and a few others. The air is cool out here, compared to the heat radiating from the whare. Matiu recounts each company of the Māori Battalion as their regions are represented by a speaker and item. Tūhoe deliver a powerful haka giving thanks.

“That’s how you do it,” Matiu says as he takes his seat back on the mahau.

“That’s how you do it,” I respond, laughing and shaking my head, inspired.

[Chapter Break]

Early next morning, three men stand knee-deep in the awa, close to where the river meets the lake. The sunrise is royal blue and purple, bright burnt orange; the waves lift with the rising wind. Mokoia stands proudly in the lake, watching.

The group are today’s kaiwero. The best the wānanga has, our ultimate toa. They have just finished a tohi, a ritual sometimes used to prepare for battle, in which negative energy is allowed to flow away with the outgoing tide. Te Rawhitiroa watches the wind scattering across the lake and knows it’s a tohu. “Everything is a sign for us and what the day may bring,” says one of the men in the water.

Back at the marae it’s all pragmatics. Chairs are laid out and wiped down, bathrooms cleaned, and we have one final debrief before our performance. There’ll be mau rākau demonstrations, speeches, presentations for the best youngsters and the best toa overall. We’ll honour two dedicated students who will be promoted to tutors, not just for their taiaha skills, but strength of character and dedication to their communities.

Local high school student Josh Yates is named taiaha toa: the standout student of the wānanga. It is a highly coveted award, and the prize is, fittingly, a taiaha.

As the wānanga nears the end, two things are certain in my mind: I will make it to that island and I will be a taiaha toa. Soon, we’ll go our separate ways. But for now, we’re together as one.

The crowd starts gathering outside at the ātea.

“Karanga mai! Karanga mai! Karanga mai!”

The manuhiri come forward and the changed men and boys of this wānanga, our tupuna behind us, begin the haka.

“Aha toia mai!”

“Te waka!”