Kiwi jackpot

It is 100 years since the tiny seeds of a plant known as the monkey peach in its native China were first sown in New Zealand. After making only modest headway in its first half-century of cultivation under the name of Chinese gooseberry, the distinctive green fruit with the stubbly brown skin has since taken off around the world. Rechristened the kiwifruit, it is now the country’s main horticultural export and looks set to become a family of fruits—some of its members very richly coloured, if these slices from experimental crossbred fruit are anything to go by.

Early mornings in June can be pretty chilly inland in the Bay of Plenty. Typically, the sky is clear, the air is still and you could expect to see streaks of mist lurking in the valleys. It isn’t quite cold enough for frost—that comes a little later in the winter—but sufficiently keen to turn your breath into fog. Those who have the option roll over in bed and wait a while, because it’s a fair bet that the rising sun will soon produce one of those settled, warm days for which the region is justly famous.

On one such morning—a Sunday, not long after dawn—I pull off State Highway 2 and clamber up a small hill to look down on Te Puke. You’d expect complete tranquillity at this time of day on a winter weekend, but this is kiwifruit country and it’s the business end of the season.

The dawn chorus is competing with the buzz of trucks and cars heading for the kiwifruit cool stores and packing sheds that dot the region. The warning beepers of the forklifts and reversing trucks float up through the still air, repeating like giant outdoor alarm clocks. Every now and then the rattle and thud of a gigantic steel door closing rolls up the valley.

The middle of June is a critical period between the fruit achieving full, plump maturity and the likely arrival of potentially disastrous winter frosts. Since mid-April a small army of hired hands has been plucking kiwifruit from the head-high vines and filling giant wooden transporter bins that can hold as much as 300 kg of fruit.

The packing sheds and cool stores are idle most of the year save for the storage of a little cheese and meat, but at this point in the season they become the crucial conduit between the kiwifruit orchards and lucrative markets all over the world. For five or six weeks they host a tense round-the-clock race against time. In the western Bay of Plenty alone there are more than 30, and from a distance one looks much like another. They can be hard to spot from the road as they’re usually nestled among the orchards, which are in turn hidden from view by the ubiquitous shelterbelts of Matsudana willow and Japanese cedar.

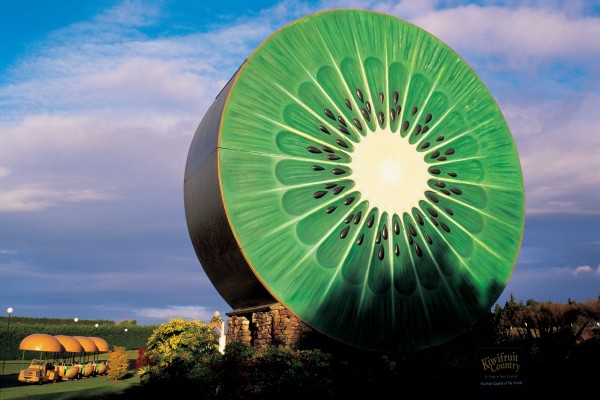

The Transpack packing shed and cool store, however—among the Bay of Plenty’s largest and most advanced—are easy to find. Just head for the region’s best-known landmark—a bright-green four-storey-high kiwifruit slice beside the road that marks the entrance to the Kiwifruit Country tourist park. Transpack is nearby.

Transpack belongs to Seeka Kiwifruit Industries, one of the biggest post-harvest operators in the business. “Packing shed”—or “packhouse”, to use the more common term—is really shorthand for what is in fact an operations base, responsible for everything from establishing and managing orchards to loading fruit onto ships in Tauranga.

[Chapter Break]

Seeka’s Ian Greaves is keeping an anxious eye on the whole process. He’s a wiry and enthusiastic man who appears to love the logistical challenge. Just as well—this season’s huge harvest has put the system under pressure. A week earlier, Seeka’s staff paused briefly to celebrate packing its 10 millionth tray in a season—a record for the company and the industry. But the fruit is still coming through and the clock is still ticking.

Transporter bins full of fresh kiwifruit are carefully stacked four and five deep under high-roofed outdoor shelters for the fruit to “cure” before being graded and packed.

“We’ve had so much fruit this season that we’ve run out of canopy space and we’re using temporary marquees,” says Greaves. “Next year we’ll have to build more canopies.”

Processing can’t be rushed. Each fruit arrives with a wound where it’s been plucked from the vine. If it isn’t allowed to dry out first in the open air, it could rot in storage or on the long trip to supermarkets overseas.

In accordance with the industry’s tracking system, each bin is bar-coded so any bad or irregular fruit can be traced back to the particular orchard in which it matured. Bins are gently emptied onto conveyer-belts that sweep the fruit into the shed, where they are assessed for blemish, sorted by size and transported to a packing station.

Inside it’s noisy and you wonder how a delicate fruit could survive the industrial atmosphere unbruised. But every machine is carefully calibrated to do no harm, and every worker is charged with being careful.

Packing kiwifruit is a highly technical business, particularly in sheds like this one, which, as well as the standard green variety, also handles the lucrative and even more tender gold kiwifruit. Not only are the thin-skinned fruit susceptible to bruising, each has a protrusion, or “beak”, on the distal (flower) end and must be packed in a specially moulded tray with a notch to protect it.

Every piece of fruit passes under the watchful eye of a computerized optical grader the size of a family car. The InVision 9000 takes up to 30 digital images of each fruit at a rate of nearly a thousand fruit a minute. It measures dimensions to within 1 mm and detects any blemishes. Anything that doesn’t make the grade goes no further.

Whether green or gold, nothing gets through without also being assessed by human eyes. Hair-netted, white-coated staff gaze down at the fruit as it passes on the grading tables, brushing gloved hands over it in the manner of a croupier spreading cards across a casino table. They’re looking for water stains, bruises, blemishes or fruit that are too flat.

Everyone works with the constant hum of the moving belts in their ears, which competes with the booming FM radio echoing off the shed’s bare walls. Perhaps the noise makes them oblivious to the fine dust that coats the place.

“No, no! That’s not dust,” laughs Greaves. “It’s kiwifruit hair. The gold ones have fine hairs,” he explains, scattering a thin layer into the air with a casual flick of the wrist. “The green ones are far coarser.”

Every now and then there’s an audible sigh of frustration as too much fruit gathers at one point and the motors driving the overloaded belts suddenly wind down and grind to a halt. Heads look up in search of the source of the problem and there’s some muttering, but the pinch points are usually cleared in under a minute.

“There are a lot of people here that have been working long, long hours,” explains Greaves. “I can see some tired eyes. No wonder people get a little cranky. We’ve been running the shed 24 hours a day for a while now. But by tomorrow we should be just about done for the season.”

Seeka has a dozen other facilities like this one. Together they handle around 15 per cent of the entire national kiwifruit crop. The company employs more than 1500 people on contract for picking and packing, and as he watches the tail end of the harvest go through, Greaves reflects on how the company has grown.

“We started in this shed in 1991, and we packed 400,000 trays. The next year we packed a million. This year it’ll be more than 10 times that”.

[Chapter Break]

With light at the end of the tunnel for Seeka’s weary packers, we drive back to the town that’s the heart of the industry—Te Puke, self-proclaimed “Kiwifruit Capital of the World”.

The sun is up properly now, and the town is coming to life. The Sunday sportsmen and dog walkers are on the move along Jellicoe Street. There’s a queue at the bakery and shoppers are filing out of the dairies with newspapers under their arms.

Seeka’s bosses gather at the company headquarters on Queen Street, an unpretentious low-rise building one block back from the main drag. Things have been going to plan at the company’s other facilities too, and the mood is one of quiet satisfaction.

Seeka’s growth and strength mirror the health of today’s kiwifruit industry overall. The furry fruit now accounts for around 30 per cent of all New Zealand’s horticultural exports, making it a far bigger business than either wine or apples. Collectively, New Zealand’s 2700 orchardists supply about a quarter of the world’s kiwifruit. Over half of exports go to Europe, nearly 20 per cent to Japan, and the rest to Australia, the USA and elsewhere. In the second half of the year, 80 per cent of kiwifruit sold in Europe comes from New Zealand.

The value of global sales has risen for the past six years in a row, and the industry is poised to crack 1 billion dollars in export earnings. Global sales for 2003–04 totalled $911 million.

While kiwifruit production is on the rise in Northland, Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and, now, Nelson, it’s the Bay of Plenty, producer of more than four-fifths of the nation’s crop, that’s driving the industry.

“Kiwifruit is now vital to the Bay of Plenty’s economy. It’s a ‘must-succeed’ crop and we have to get it right,” says Tony de Farias, who, as managing director of Seeka, has overseen the company’s growth for 10 years.

“Markets and exchange rates will go up and down, but you can’t do much about that,” he says, leaning across the table in the no-frills boardroom. “The reality is that we are a long way from the world’s main markets, so we have to get a premium for our fruit—and we can only do that if we maintain the highest possible standards.”

[Chapter Break]

While it is true that seeds of Actinidia deliciosa—the Chinese gooseberry—were first planted in Wanganui 100 years ago, and that the first commercial plantings were there and in the north, it’s the orchards on Number 3 Road, to the west of Te Puke, that are now regarded as the cradle of kiwifruit.

It was there, on a half-acre block in 1932, that Jim McLoughlin first produced commercial quantities of Chinese gooseberries, when all else around were dairying or growing citrus. Twenty years later he raised the first ever export consignment, 20 cases of his fruit being shipped to London’s Covent Garden market. These were well received, but McLoughlin had so many setbacks with his exports in the years immediately following it is astonishing that he persisted.

Things looked up in 1959, when Turners and Growers (a leading fruit exporter of the day) sent 100 cases of what it called melonettes to San Francisco. On learning that melons and berries attracted substantial duties, company boss Sir Harvey Turner came up with the name kiwifruit in the company’s boardroom. In one notable publicity coup, the wife of Russian premier Nikita Kruschev was served kiwifruit during a summit visit to the US.

A strike by British dockworkers in 1960 ruined one entire shipment, leaving exporters and growers in New Zealand with hefty bills. After years of toil there was still no hint that kiwifruit production would grow to become a billion-dollar industry. But the adoption of the ‘Hayward’ cultivar as the industry standard proved a breakthrough. First developed in the 1920s by Auckland nurseryman Hayward Wright, this fruit was denser, brighter and more robust than the ‘Allison’, ‘Monty’ and ‘Bruno’ varieties that had previously predominated. (Kiwifruit Country has a stand displaying these old varieties supplied from the HortResearch collection, but so familiar has ‘Hayward’ become that its predecessors look strange. ‘Allison’ and ‘Monty’ are small and dark, while ‘Bruno’ is longer, hairier and skinnier. They are as peculiar as flat apples or straight bananas.)

‘Hayward’ kiwifruit’s biggest plus was that it held its condition much better than other varieties on the long voyage to export markets, and in the 1960s the first concerted efforts to promote kiwifruit began to pay off. One imaginative campaign in the US claimed: “This new fruit is so scarce and delicious it seldom leaves its home town. If you’re ready for it, you had better order now… they’re scarcer than trout’s fur, hen’s teeth and screen doors on submarines.”

In 1970, the government got in on the act. Keen to diversify primary production and encouraged by the Bay of Plenty’s pioneer growers, the Department of Industrial and Scientific Research (DSIR) bought 60 acres of farmland on Number 1 Road, to the south-east of Te Puke. Two years later, Russell Lowe—fresh from working with apples in Nelson—arrived in Te Puke and was set to work on citrus, subtropicals and the “new” crop, kiwifruit.

More than 30 years on he’s still there, as part of the world’s largest kiwifruit breeding effort for what is now the Crown Research Company HortResearch. The 40 ha property has its own modern offices, fleet of vehicles, laboratory and cool store, yet some of Lowe’s first trial blocks of ‘Hayward’ plants are still flourishing. Standing under a canopy of those leafy vines, he recalls that expectations weren’t high back in 1972.

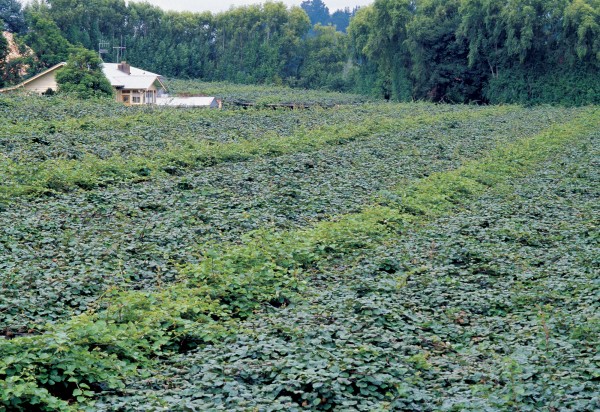

“The locals in Number 3 Road said, ‘They’ll never grow kiwifruit over there in Number 1 Road. It has to be over here.’ Today that seems absurd. The orchards along the two roads are barely three kilometres apart, and nowadays kiwifruit occupies more than 11,000 hectares of the Bay of Plenty.”

The district has proved ideal for kiwifruit. There’s plenty of flat land with fertile and free-draining soil. Roots have no problem penetrating, yet the ground is generally firm all year round. The region enjoys high sunshine hours in summer and a generally frost-free spring and autumn. In winter, mild chilling encourages budding at the right time but frosts are mercifully short. Rain falls throughout the year, and extended dry periods are rare, so established plantings survive without irrigation.

As vines all around Te Puke matured, investors sensed huge profits were just round the corner and moved in. Te Puke quickly shook off its reputation as a sleepy hollow, and kiwifruit orchards spread across the Bay of Plenty, from Opotiki in the east to Katikati in the north.

Katikati is the home of Rosalie Smith, who reckons she’s probably written more about kiwifruit than anyone else alive. Her family were dairy farmers nearby when she became a farming correspondent for the Bay of Plenty Times in 1969.

“The whole Bay of Plenty was just grass paddocks, dairy cows, a few hedges and a bit of pine,” she recalls. “There were a few orchards, scattered around like measles on a body, but it all changed in such a short space of time. Where five families round here once lived down a side road on five dairy farms, now there’ll be seventy. The population increase has been almighty—and it’s still going on.”

One of Smith’s best-known articles is written in the form of a story being told by an old woman to a granddaughter sitting on her knee. Creatures called dinosaurs once ruled the earth, she explains, but then they disappeared. Then came beasts called dairy cows, she tells the girl, before they too mysteriously vanished, pushed into extinction by kiwifruit, persimmons, avocados and other fruits.

Smith has now retired to the outskirts of Katikati. “There would have been nothing here 30 years ago,” she says, “but now there’s kiwifruit and avocados just across the road.”

Like many dairy farmers, the Smiths sold off much of their land piece by piece to would-be orchardists in the 1970s and 80s. Some buyers were displaced farm workers and some were labourers who’d been hired to develop existing orchards and wanted to take the plunge themselves. But when the boom began, the government’s tax incentives and the prospect of profits attracted those with no agricultural experience at all.

But Katikati was a sideshow—Te Puke was the real boomtown, and the source of many tales of the nouveau riche excesses of freshly minted kiwifruit millionaires. It was said that anyone with 10 acres (4 ha) or more of kiwifruit was a paper millionaire, and by 1985 there were more than 50 millionaires within a 1.5 km radius of the town’s post office.

“There were plenty of outrageous stories,” Smith recalls, “and you never knew how many of them were true. But some certainly did go out and buy cars for everyone in the family and would think nothing of flying to Sydney to freshen up the wardrobe.”

National Party leader Don Brash also had a grandstand view of the boom years—and the beginning of the bust that followed. Under the heading “Other Interests” on his parliamentary web page, just one item is listed: kiwifruit growing.

“I have an orchard near Pukekohe. I bought it as bare land in 1980, when many people were getting into it for tax reasons. But unlike many of those, I’ve remained an orchardist long after the tax benefits disappeared.”

His best crop was 31,000 trays, but in 2004 he has managed only two-thirds as much.

“I think it’s time to replace some of the males,” he says earnestly, scratching his chin. “It hasn’t been a particularly profitable venture for me, but I’ve enjoyed it and I have no plans to sell.”

Kiwifruit became much more than just a sideline for Brash on April Fools’ Day in 1982, when he was appointed managing director of the New Zealand Kiwifruit Authority, the body that granted licenses to exporters, set quality standards and promoted kiwifruit overseas.

“In my first year in charge, we produced 4.5 million trays. By 1988 it was 10 times as much. Now, if you increase supply tenfold, you’ll get a fall in the market price,” he says.

Sure enough, too many exporters were sending too much fruit to markets also being swamped by kiwifruit from growers overseas, some of whom were making full use of prime rootstock and seedlings sold by New Zealand growers for a quick profit. The price of the fruit plummeted. Many growers were forced off their land and investors ran for cover. There was no quick recovery. A Ministry of Agriculture review in 1994 noted that land with kiwifruit on it had become cheaper than bare land.

But when the great and good of the industry gathered in May 2004 in Mount Maunganui to mark the Chinese gooseberry’s New Zealand centenary, they were able to celebrate a dramatic turnaround. Once broke and in turmoil, the kiwifruit industry is now highly profitable again. Orchard values are rising and kiwifruit is outperforming most other primary industries.

How has this been achieved?

“I well recall the day the chairman of the Apple and Pear Marketing Board sat in my office and said, ‘Mark my words. You too will soon have a single-desk operation’,” recalls Brash. After the disastrous fall in export prices in 1988, that prediction came to pass. But two years earlier, Brash hadn’t been able to see it happening. “The Bay of Plenty growers were proud of their multiple-exporter system and wanted to see it continue,” he recalls.

Craig Greenlees, a 20-year industry veteran and founder of the kiwifruit company DMS, was one such. “The kiwifruit industry is full of enterprising people who wanted to choose and do things as they saw fit,” he says. “To agree to a system that took away choice wasn’t something they liked.”

Grudgingly the growers surrendered their precious sovereignty to the New Zealand Kiwifruit Marketing Board, which took over all exporting and marketing and effectively bought the crop from them. But the board couldn’t halt the global glut, and Greenlees recalls that by 1993 he wanted to reclaim the right to sell his own crop.

“I thought we should all just sell the next crop as best we could. I lost that argument at the time and I’m pleased I did because the industry wouldn’t be in the strong position it is now without the single-desk system.”

Five years ago the board was corporatised, becoming Zespri International, and the company has since presided over the transformation of kiwifruit’s financial fortunes. As if to illustrate how complete is the turn-around, its current chairman is none other than former single-desk sceptic Craig Greenlees.

Zespri developed its structure in consultation with the growers, retaining them as its only voting shareholders. Corporate investors, who would love to have a stake in the newly profitable industry, hate the arrangement, but it’s given kiwifruit growers a measure of stability that other primary producers envy.

One grower said to me: “Any idiot can sell a million trays of kiwifruit. It’s getting rid of the lot at a decent price that’s the hard part.” That, in a nutshell, is Zespri’s mission, and success is the only way to keep its demanding shareholders off its back.

[Chapter Break]

Zespri’s Corporate home in Mount Maunganui is modern yet modest—considering it’s the nerve centre of a billion-dollar business. No outlandish sculptures in the foyer, no grand corporate art on the walls. “They wouldn’t let us get away with that!” splutters chief executive Tim Goodacre. “Kiwifruit growers can smell waste a mile off.”

When Zespri’s bosses decided in 2002 to uproot the company from Auckland and transplant it in the Bay of Plenty, it took out newspaper ads touting the “stunning Bay of Plenty” as a place “where a professional career and lifestyle values can meet in perfect harmony”.

A little over the top perhaps, but driving to Zespri’s HQ on Maunganui Road on what is probably a gridlocked Monday morning back in the big smoke, you see what they’re getting at. It’s another of those clear sunny days that make a mockery of winter, the Mount is a splendid sight in the middle distance—and you can park right outside the office for free.

The PR seemed to work on Good-acre, an affable 50-year-old Australian who, along with his wife and young son, swapped Melbourne for Mount Maunganui when the move was being made. Goodacre grew up on a grain, cattle and sheep farm in central New South Wales and became a senior executive at Australian wheat giant AWB. Like Zespri, this is a former producer board (the Australian Wheat Board) restructured into a company controlled by growers—around 42,000 of them, which is about 16 times as many as Goodacre deals with now.

Goodacre believes that few New Zealanders realise what has been achieved with kiwifruit in their country. “It’s one of only four newly commercialised fruit varieties in the last 100 years,” he says (the others being avocados, also big in the Bay, blueberries and macadamia nuts). “The very low level of success for new varieties around the world means this is an achievement that’s right up there.”

While the global glut of the 1980s and 90s wreaked havoc on the industry in New Zealand, millions of overseas consumers acquired—and retain—a taste for kiwifruit. Zespri has successfully exploited the lasting demand, and the days when large chunks of the annual crop remained unsold are long gone.

Furthermore, where foreign kiwifruit once spelt disaster for New Zealand growers, now it’s part of Zespri’s master plan. The company has licensed Northern-hemisphere growers in California, Italy—today the world’s largest producer of kiwifruit—and even Iran to ensure that Zespri-branded produce is available in key world markets all year round. Many accomplished Bay of Plenty growers and kiwifruit entrepreneurs are now scattered among these countries running joint ventures for Zespri.

“The great benefit is that we don’t have to fight for space in the supermarkets when New Zealand fruit gets to foreign markets,” explains Goodacre. “We can hold our spot all year round.”

Zespri’s biggest single triumph, however, has been the introduction of the gold kiwifruit. Marketed overseas as its sweeter yellow flesh and soft skin have made it a stunning success, particularly in Asia. Zespri claims that in 2004, just seven years after it was introduced to the market, the new variety pulled in a remarkable $170 million in global sales.

Gold kiwifruit’s scientific name is Actinidia chinensis, although before commercialisation it was known simply as Hort 16A—the reference number of the block in which it first flourished in HortResearch’s Te Puke orchards.

Hort 16A originated from two introductions of Actinidia material to New Zealand, in 1977 and 1981. HortResearch scientist Mark McNeilage made the crosses that produced the seedlings planted at Te Puke, where Russell Lowe selected them for further evaluation. An advantage of gold kiwifruit is that ‘Hayward’ vines can be grafted to grow it.

If gold kiwifruit had arrived 20 years earlier, there would have been a mad scramble among orchardists to grow as many as possible. Today, though, Zespri only grows and sells the quantity it thinks will secure a premium price around the world, and currently estimates that should constitute a sixth of the national crop. Also, learning from past mistakes, the company has purchased the Plant Variety Rights from HortResearch (who obtained them in 1995) so only licensed Zespri growers are permitted to grow the gold variety and cash in on the surging demand.

Goodacre reckons the kiwifruit industry has—at last—got the right structure, and other primary industries could follow it.

“Zespri itself is a just a marketing company,” he says. “The growers who own us want us to take long-term decisions to sustain the industry, because they have an investment in orchards which is long-term. Compare that with a traditional trading company with a raft of shareholders who are not necessarily part of the industry. We spend as much as six million dollars a year on research and development. There aren’t many businesses that would allow you to make those sorts of longer-term decisions.”

[Chapter Break]

There are few in the industry who dispute that Zespri’s marketing has been good so far, but some argue that it gets too much credit for the industry’s current rude health.

“Kiwifruit would never have got off the ground in the first place without entrepreneurial growers and exporters, who took the risks and created all that demand,” says Seeka’s Tony de Farias. “And the same kind of people did everything they could to make the industry viable again after the bad years. Everything’s more efficient now. In 1992, each hectare produced around 3500 trays on average. Ten years later it was 6000 per hectare, and costs are a fraction of what they used to be.”

But the very presence of Zespri’s one-stop shop for exporting and marketing limits the options for other businesses. It’s become a source of tension in an otherwise unified industry.

Right now, Seeka itself probably has the resources and expertise to sell and export the fruit it grows and packs on behalf of its contracted growers, but that is not the direction it’s headed: all fruit is handed over to Zespri. In fact, Seeka has just developed an exclusive long-term marketing contract with Zespri which would continue even in the event of deregulation. And even though companies like Seeka are critical to the industry’s success, unlike the growers they don’t have a direct stake in Zespri except insofar as they are orchardists in their own right.

“The downside of any monopoly is—well, that it is one,” says de Farias. “The danger of any monopoly is that it can become complacent. We compete vigorously with other packhouses. But Zespri doesn’t have any competitors.”

Some in the industry mutter darkly about the agitation of ambitious packhouses, fearing they could upset the system in pursuit of their own individual benefit, but de Farias says it’s really about ensuring a strongly marketed product.

“In our view there will be a time when things won’t be so regulated. Who knows when that will be, but we need robust commercial arrangements so that we won’t just fragment and fall apart like the apple industry has done.”

But if Zespri continues to rack up record sales overseas and to return the profits to growers as it has for the past six years, calls for reform or revolt are unlikely. The company would have to “stuff up in a big way” to lose the confidence of growers now, according to Greenlees, “and if that ever happens,” he says, “we’ll probably have deserved it.”

But factors beyond the control of anyone in the industry could also take the steam out of kiwifruit’s second great surge. The fact that Zespri’s government-endorsed monopoly gives New Zealand’s growers a competitive advantage in world markets hasn’t gone unnoticed by free-trade advocates overseas. It could conceivably fall foul of future free-trade deals or World Trade Organisation agreements. Publicity surrounding the lifting of the GM moratorium might undermine Zespri’s clean green brand overseas. A major GM scare or accidental release would be worse—as would any serious outbreak of disease or blight affecting the vines.

Business strategists also point to the dominance of the Bay of Plenty as a potential weakness. A climatic catastrophe there would put more than four-fifths of the national crop in jeopardy. In the longer term, climate changes driven by global warming could also affect productivity in ways yet unforeseen, although the Ministry of Agriculture’s research also suggests—somewhat optimistically, perhaps—that whole new regions could support vines if current trends continue. Kiwifruit in Canterbury, anyone?

And—of course—the foreign competition hasn’t gone away. Italy now produces more kiwifruit than New Zealand. Chile is still in the game in our hemisphere, and the country that gave us the fruit in the first place is also gearing up. A HortResearch study in 2003 found that China’s acreage under kiwifruit increased threefold between 1998 and 2002, and Rosalie Smith says China is looming over us “like a giant thunderstorm”. Russell Lowe, on the other hand, has toured areas under development in China and reckons it will take years for Chinese production to match New Zealand’s export quality fruit.

If current plantings succeed the yields will be enormous, but Chinese fruit may never be quite as good, he says. China lacks the cool stores and distribution for really effective exporting, and even after it gets on top of those problems, exports of Chinese kiwifruit will principally be a problem for the established growers in the Northern hemisphere, he believes. Still, China has the advantage of a huge internal market for the fruit and it may be that in the foreseeable future a location in the Yangtze valley will claim from Te Puke the title “Kiwifruit Capital of the World”.

A more immediate problem lies closer to home: where will the Russell Lowes of the future come from? Even though kiwifruit’s booming again, it’s failing to attract the brightest and the best students. Enrolments in horticultural science degree courses are the lowest in two decades, and graduate and postgraduate numbers are well below those needed to sustain production and research.

“Students want to go into law and other professions—the so-called money-making ones,” says Lowe, “but the scientific community is trying to get a better profile to attract bright people back into science and horticulture, because we all have to retire sometime. This is a fascinating job, but I don’t want to be doing it when I’m 80.”

Back in her Katikati garden, Rosalie Smith echoes Lowe’s fears about kiwifruit’s succession planning. “It’s out of favour. Out of fashion. The money we make at the Fruits of Katikati festival we spend on scholarships for people studying horticulture. We’ve had great difficulty finding anyone who wanted these scholarships.”

Most of the best orchards today, says Smith, are owned by people who are pushing 50—or beyond. Without fresh blood, she warns, the kiwifruit industry won’t renew itself properly. Orchard prices are high again—too high for younger people wanting to make a start, and there’s little land available for new orchards. In fact, some vines have been lost to the expansion of Tauranga and other Bay of Plenty towns.

Even so, says Smith, kiwifruit still manages to attract new people who are keen to have a go at making something from a small rural holding. And in the Bay of Plenty, kiwifruit has also become a profitable form of diversification for traditional pastoral farmers—and Maori.

[Chapter Break]

To learn more, I return to the giant green slice of kiwifruit beside Highway 2 above the Kiwifruit Country theme park and its orchards. Next door, Seeka’s sheds are still a hive of activity. (By the time the last fruit fills the final cardboard tray, the company will have cleared more than 11.5 million trays.)

Several times a day huge freight trains thunder by, hauling logs and other goods between Kawerau and Mount Maunganui. Kiwifruit Country has its own train—a set of cute kiwifruit-shaped “kiwi-karts” hitched to a tractor that takes tourists on a tour of the park’s working orchards.

Kiwifruit Country was built in the late 1970s to cater for tourists wanting to see how their favourite fruit was grown—a blessing for orchard owners grown weary of fruit fans. In the 1990s, Taiwanese owners took over the park and turned parts of it into an antipodean version of the Tiger Balm Gardens, adding grandiose water features, raised gardens and huge gaudy concrete dragons. It wasn’t a hit. By 2002, Kiwifruit Country was running down and

the business was put up for sale. A consortium of Maori kiwifruit orchard trusts and individual investors swooped.

The chairman is a prominent local Maori, Warwick Tapsell. “He’s practically royalty,” I was told when I mentioned our meeting to a Te Puke businessman. I wouldn’t have known. He’s a big man, yet softly spoken, friendly and modest. Apart from a few years at Canterbury University as a young man, he’s lived all his life in the Bay of Plenty, most of it dairy farming and growing kiwifruit.

“This place had been seen as drifting away from the community, but it’s a great asset,” he tells me as we stroll through Kiwifruit Country’s landscaped garden, the backdrop for many wedding photos. “It’s a good orchard too, but its real potential is as a tourism and hospitality resort. Maori are really comfortable with both those things—much more so than investing in shares or developments in town. This takes us back to our own lands, and into a developing industry compatible with our aims and aspirations.”

In days gone by, he says, all this was Maori land—part of a block that stretched from Maketu Road to the Kaituna River. Generations of Te Arawa and Ngaiterangi people grew vegetables there. Loosely translated, its name—Pukai Ngataru—means “place of the burning garden rubbish”.

After European settlement, the block was subdivided many times. The parcels that remained in Maori hands were mostly too small for effective farming, and many were leased to local dairy and cattle farmers. But by the time kiwifruit boomed in the 1980s, many leases were running out and the land was coming back. “Suddenly, a block that was only 10 or 20 acres (4–8 ha) was economic to grow kiwifruit,” says Tapsell.

A number of trusts were formed, and money was borrowed from the Department of Maori Affairs to get the vines planted.

“From Welcome Bay to Matakana Island, Katikati and Maketu, people were farming their ancestral lands again. Twenty years later all of them are getting good incomes and are clear of debt. That’s why we can invest in other assets like this. There are lots of shareholders, which makes it complicated in one way. But it’s simple in another because it’s a shared vision. Everyone who’s invested has tribal linkages into this land right here.”

The purchase of Kiwifruit Country, Tapsell insists, is an opportunity for Maori who have been successful in kiwifruit to take another step forward.

“A lot of what they’ve achieved is hidden behind hedgerows. But Kiwifruit Country is higher profile. People look at it and ask, ‘Who runs this place?’ and find out that it’s people with a long track record, and that not every Maori business fails as soon as it starts.”

[Chapter Break]

Inside the Kiwifruit Country complex, I’m treated to muffins from the café—kiwifruit muffins the size of softballs, studded with huge nuggets of warm, gold kiwifruit. Next door, a pair of young German designers are beavering away on laptop computers in one of the meeting rooms, planning a conversion of the main building. Tapsell and his board of directors intend making Kiwifruit Country the region’s best hospitality venue, and they’ve already claimed a top Bay of Plenty tourism award in 2004.

Tapsell is encouraged by the enthusiasm he sees in the visitors every time he accompanies a group on a tour of the orchards. He takes them to a special roped-off block where the vines running over the pergola frame groan with precious gold kiwifruit.

“Once they get under here and see all the fruit hanging down, they’re amazed. To us it’s like wallpaper, but most of them have never seen kiwifruit growing anywhere in the world before and they’re fascinated. Hundreds of photographs are taken right here.”

But not everyone taking the tour is a bona-fide tourist.

“We had one tour group on the kiwi-karts a while back who seemed to be concentrating very hard. One was asking a lot of detailed questions about sunshine hours, supplementary irrigation and so on. Turns out they were kiwifruit growers from southern France,” he laughs.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that a little low-level industrial espionage goes on. New Zealand’s kiwifruit industry can be justly proud of the way it has continually refined its growing methods and developed ingenious solutions to perennial problems.

Take pollination. This has always been crucial to a good crop, yet improving on the birds and the bees stumped growers for years. Kiwifruit vines are dioecious; that is, individual plants are either male or female. Both sexes flower in spring, males typically four to five days before females, but only females bear fruit, and only when pollinated by males. For years it was assumed a combination of wind and dry conditions did the trick so long as enough males were present.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that the behaviour of bees was studied, when Canadian specialist Cameron Jay, on a year’s sabbatical, showed how bees could boost pollination rates. Growers began to change the composition of their orchards and hire beehives when the vines were in flower.

Pollinating by hand—whereby fresh pollen on a male flower is gently rubbed onto the stigmas of a female flower—also proved effective but was far too time consuming. In the late 1970s, the Pollen Aid spray-on system (developed by MAF Ruakura) made it possible to apply water-borne pollen to the vines regardless of the weather or presence of bees. Later, blower-assisted pollination techniques took over, whereby pollen is first collected then wafted through the flowering orchards.

Harvesting pollen from early male flowers has become a lucrative trade in itself. Several companies now sell dried and frozen pollen, couriering it around the country. Vines flower earlier in the north than in the south, allowing southern growers, particularly those in the Nelson area, a head start pollinating their female plants. But the pollen is very expensive, and blowing it through an orchard is a scatter-gun approach.

Recently, Tauranga horticulturalist Graham Willacy brought bees back into the equation with BeeFORCE, an electronically programmed system that delivers rations of pollen to bees as they leave the hive, which they then distribute around the orchard. The intervals at which pollen is delivered can be adjusted to suit the temperature and sunshine conditions, and the bees can also be loaded up with bioagents to control infections such as botrytis and sclerotinia.

The emphasis of research is on identifying ways of working with nature to achieve better crops. Almost the entire industry has adopted the KiwiGreen pest management programme. Instead of spraying with pesticides at various fixed times during the year, growers now spray only when they really need to. The goal is to produce fruit with no detectable pesticide residue at harvest time and eventually to do away with broad-spectrum pesticides altogether. There is also a small but active organic sector for which fertilizers and pesticides must be derived from animal or vegetable matter.

Several companies have now taken up the challenge of adding value to their crop. A sweep though Kiwifruit Country’s souvenir shop reveals a surprising range of processed products: moisturising cream with kiwifruit extract made in Auckland, kiwifruit chocolate from Christchurch, even kiwifruit-liqueur dessert sauce with flakes of gold leaf floating in it.

Most of this is boutique-scale production that will hardly make a dent in the national balance of payments, but some companies are making genuine inroads overseas. Auckland-based juice company Nekta International is selling kiwifruit juice and purée in 20 countries around the world, and Zespri too has got in on the act with a subsidiary—Aragorn Limited—to develop new kiwifruit products for export through joint ventures and overseas partnerships.

The products that may really pay off, though, are those that harness kiwifruit’s nutritional and medicinal qualities and target the substantial premium that health-conscious consumers in rich countries are willing to pay.

“Just the other day I was told Spanish doctors now tell patients to eat kiwifruit every day if they want to maintain their traditional diets,” de Farias tells me. “New research is coming up all the time in Europe saying how good it is.”

Kiwifruit people love to tell you that the fruit contains more vitamin C per unit of weight than oranges and almost as much potassium as bananas. Then there’s the magnesium, the vitamin E and the dietary fibre, not to mention the antioxidants and the enzymes known to aid digestion. And even the most casual consumer will be aware of the fruit’s laxative properties.

Sensing potential profits in the wider field, in May 2004 Seeka bought a stake in Auckland company Vital Foods, which specialises in what it calls kiwifruit-based nutraceuticals. It markets capsules containing a kiwifruit enzyme complex called zyactinase that sell for more than a dollar apiece in high-value markets such as Germany and Australia. They aid digestion and are claimed to relieve the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, an ailment on the rise in affluent countries all over the world.

For 12 years Vital Foods has been manufacturing kiwifruit products and it owns the rights to specialist technology for formulating medications from the fruit. The company also makes kiwifruit drinks sold in supermarkets all over New Zealand and used in hospitals, where doses are commonly given to patients with digestive difficulties. It’s also marketing a new freeze-dried kiwifruit powder—Digestezy—which, the company claims, can be reconstituted with the digestive properties of the enzymes intact, and is working on extracting the fatty acids omega 3 and 6 from kiwifruit seeds, which could prove an excellent use for reject or surplus fruit. Although these dietary supplements can be obtained more cheaply from fish oil, vegetarians prefer a plant origin.

[Chapter Break]

As the kiwifruit industry embarks on its second century, however, the real ace in its pack remains the quality of the high-end research and development largely performed by HortResearch. The success of gold kiwifruit was no fluke: it was the pay-off from a 30-year commitment to R & D that no other country can match.

It was also the result of great strategy. Even as ‘Hayward’ kiwifruit was proving a winner and making New Zealand growers unprecedented fortunes, there was a clear-eyed understanding that new varieties could one day be needed and that it would take time for these to reach fruition.

In the humble surroundings of the Te Puke research orchards, Russell Lowe, Alan Seal and their colleagues are striving to repeat the trick. East Asia, particularly China but including Korea, Japan and parts of Russia, is home to more than 60 species belonging to the kiwifruit genus Actinidia. The range of fruit produced by all these species is vast. Many are not hairy, and they come in a great variety of colours, shapes and flavours. Some, for instance, such as A. polygama, are slim, red and peppery. Not all are pleasant eating, but even those that are not may bear fruit with some commercially desirable properties, such as a strong colour, a long shelf life, cold tolerance, resistance to bruising or easy peeling. Some of the more “left-field” crosses are made by Ron Beatson of HortResearch, Motueka. He is especially interested in cultivars with rich red colours, and is experimenting with crosses involving A. macrosperma, A. valvata, A. polygama and A. melanandra, all of which have red or orange fruit. Then there are A. kolomikta, from Siberia, and A. eriantha, which has a particularly high level of vitamin C.

At HortResearch in Te Puke there are about 20,000 seedling vines belonging to 20 Actinidia species and crosses under evaluation—the largest collection of such plants outside China. Hopes are high for the small, sweet, hairless Actinidia arguta, often described as a kiwifruit crossed with a grape. It is eaten skin and all. There’s a promising larger fruit the size and shape of an apple, and progress is being made on easy-to-peel fruit. When pushed, Lowe declares a preference for a new variety they’ve developed with red flesh and a sweet taste. “I reckon that one’s got a chance,” he says, hiding a grin under his sunhat.

When HortResearch does develop another new commercially attractive variety, Zespri will again have first-mover advantage. HortResearch and Zespri recently concluded a deal which means that Zespri is committed to long-term research funding in return for the intellectual property rights to the results of the breeding programme. A win-win situation, according to Lowe.

“We could have been licensing our selections to an offshore company, but that won’t happen now. It’s a case of New Zealand research for New Zealanders.”

Thus, should the world’s fickle fruit eaters tire of the familiar green variety—or even the golden new kid on the block—there’s every chance they’ll be seduced by something fresh that’ll have sprung up here, on Number 1 Road, RD2, Te Puke.