Joseph Banks

In 1767, the year that Endeavour put to sea, Banks was 25 years old. He had inherited a considerable fortune, the estate of his father who had passed away in 1761, and had grown used to indulging his taste for life’s richer pleasures. He was a socialite among a crowd that included scientists, philosophers, artists, courtesans and scoundrels. It was a lively time for the arts and sciences—James Hargreaves had just patented the “spinning jenny”, a machine for spinning cotton credited with kick-starting the Industrial Revolution. The microscope and the telescope were pushing the frontiers of the known universe and scientists and philosophers throughout Europe were challenging superstition and religion.

Like many of his contemporaries, Banks embraced the Enlightenment notion of Progress—that our growing ability to manipulate the world through technology would result in benefits for everyone. As a fellow of the Royal Society he positioned himself at the hub of this revolution of ideas, networking and engaging in lively correspondences with leading scientists, philosophers and explorers. His interest in the natural sciences encompassed zoology, geology and ethnography, but it was botany which consumed him.

Botany was in fashion. In the 1760s, plant hunters were sending back thousands of specimens from North America, India and China, satisfying a growing appetite among 18th-century landscape gardeners for the new and exotic. Settling on a unified strategy for naming species and imposing order on the natural world was also becoming an issue. Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) had recently developed a revolutionary new system of classification in which he arranged flowering plants into families based on their sexual characteristics—the number of male stamens and female pistils in each flower.

The Royal Society was sponsoring the world’s first scientific voyage of discovery and Banks perceived a great opportunity to make his name as a scientist. The converted Whitby collier Earl of Pembroke, renamed and commissioned as HM Bark Endeavour, was to be sent to the newly discovered King George’s Island (Tahiti). Its primary goal was to record the Transit of Venus—the time taken for the planet Venus to travel across the face of the sun, data from which scientists could calculate the distance from Earth to the sun.

However, Banks was more interested in the opportunity the voyage afforded to botanise in virgin territory. He lobbied hard to win a place on board, volunteering to put up £10,000 of his own money to recruit and equip the science team for the voyage. However, it was still the Admiralty’s gig and their aristocracy had the final word on selecting a principal scientist regardless of what the Royal Society or any of its illustrious fellows had to say about it. Fortunately, one of Banks’ drinking buddies was the Earl of Sandwich (or “Jemmy Twitcher” as he was known to the demi-monde), who was not only famous for his debauchery but also the First Lord of the Admiralty.

[Chapter Break]

At 2PM on August 26, 1768, Endeavour sailed out of Plymouth Sound with Joseph Banks and his good friend Daniel Solander, the young Swedish naturalist, on board. Banks’ entourage also included the naturalist and instrument maker Herman Sporing, landscape artist Alexander Buchan and the gifted young illustrator Sydney Parkinson. From Revesby, Banks’ Lincolnshire estate, came two young African servants and his two best dogs—a spaniel and a greyhound. There was also a mountain of scientific paraphernalia.

As John Ellis, another fellow of the Royal Society, observed: “No People ever went to sea better fitted out for the purposes of Natural History. They have a fine library: they have all sorts of machines for catching and preserving insects; all kinds of nets, trawls, drags and hooks for coral fishing, they have even a curious contrivance of a telescope, by which put into water, you can see the water a great depth, when it is clear…”

There were a total of 96 men and boys on the ship, including gentlemen scientists, ship’s officers and a 12-man militia. Supplies included 1200 gallons of beer, 34,666 pounds of bread, 6000 pieces of pork, 4000 pieces of beef, 1500 pounds of sugar and a goat to provide fresh milk for the gentlemen and officers. Below decks the common sailors strung their hammocks the regulation 14 inches apart, and the accommodation provided for the officers and gentlemen scientists was accurately referred to as “hutches”. At 6’5” Banks towered over his shipmates and was in constant danger, leaving chunks of his scalp all over the woodwork.

He quickly established a working routine, botanising ashore wherever conditions and the captain would allow it. On returning to the ship, he and Solander would lay out the contents of their collecting baskets in the Great Cabin, which Cook, who enjoyed the company and lively conversation of the young men, generously made available to them.

The detailed descriptions were written up while the plants were still fresh. At the same time, Parkinson would sketch them, adding accurate colour references so that unfinished drawings could be completed at a later date if necessary. Each new plant was then put into a folded sheet of paper and left in the sun to dry. Whenever possible, this drying process was done ashore by spreading the papers out on a sail. In Banks’ own words,

“…one person is intirely employd in attending them who shifts them all once a day, exposes the Quires [folded papers] in which they are to the greatest heat of the sun and at night covers them most carefully up from any damps…”

Once dried, the plants were placed in fresh quires of paper and bound in bundles for storage. Realising he’d need a lot of paper for this process, he had brought a large supply of printers’ proofs. One of the surviving bundles still has plant specimens nestling among the pages of Joseph Addison’s Notes upon the Twelve Books of Paradise Lost.

[Chapter Break]

Just over a year later, the first part of the Endeavour’s mission had been accomplished, but with mixed success. The observations made from Point Venus on the island of Tahiti on June 3, 1769, did not provide the conclusive data that was hoped for—intense sunlight filtering through Venus’s atmosphere had fuzzed the edge of the planet’s silhouette and Cook’s record of the time taken for the transit to occur differed by 42 seconds from that recorded by the ship’s astronomer, Charles Green, a difference that was too significant for an accurate calculation of the distance from the Earth to the sun.

What’s more, three sailors had already drowned on the voyage and another had managed to drink himself to death. Banks’ team wasn’t immune to tragedy either. The two black footmen from Revesby froze to death during an ill-advised collecting trip in Tierra del Fuego, a fate shared by one of the dogs. In Tahiti, Alexander Buchan died following an epileptic seizure.

On the bright side, in Moorea Banks had persuaded Cook to allow a high-ranked Polynesian to join his entourage. Tupaia was an Aroi, a member of the Polynesian cultural elite with specialist knowledge of custom and religious matters, and a skilled navigator. He and Banks became good friends. Banks might have imagined showing off the Polynesian princeling to the high-life crowd back in London, but Tupaia was much more than an exotic human trophy. His real worth to the success of the expedition soon became evident.

By September 23, 1769, the ship’s supplies of fresh food were running low and many of the pigs and chickens taken aboard in Tahiti had died. Even the ship’s biscuit, the marine substitute for bread, was crawling with insects. With the stoicism attained in the notorious public school refectories of Harrow and Eton, Banks recorded, “I have often seen hundreds nay thousands shaken out of a single bisket. We in the Cabbin have an easy remedy for this by baking in an oven, not too hot, which makes them all walk off.”

Characteristically, the botanist notes that the escaping bugs “are of 5 kinds, 3 Tenebrios, 1 Ptinus and the Phalangium cancroides”. Nevertheless, like everyone else, he was eager for any sign of approaching landfall and an opportunity to take on fresh food and water.

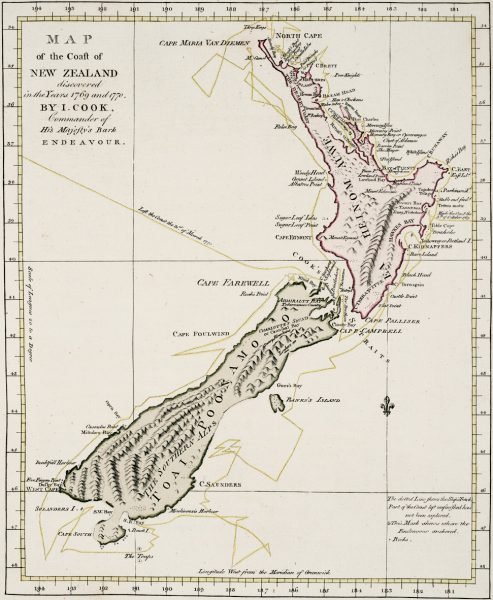

In accordance with the Admiralty’s orders, Endeavour was heading for Nova Zeelandia. Almost all that Banks would have known of the land came from Alexander Dalrymple’s Account of the Discoveries Made in the South Pacific Ocean, which detailed the experiences of the Dutch navigator Abel Tasman, the only other European explorer to have visited the archipelago more than a century earlier.

Without the benefit of a translator, the Dutch had catastrophically misjudged the tenor of their reception. One of the waka had charged the cockboat, deliberately ramming it. Sailors were pitched into the sea, others clubbed to death—Tasman lost four men, and several Maori were killed.

But there’s nothing in Banks’ journal to suggest anxiety, only a growing sense of excitement.

On October 2, 1769, Sydney Parkinson recorded that, “the sea is as smooth as the Thames, and the weather fair and clear. Mr Banks went out in a little boat, and diverted himself in shooting of Shear-waters, with one white Albatross, that measured, from the tip of one wing to the other, ten feet, seven inches; and also picked up a great many weeds of various kinds.”

Banks himself wrote: “Now do I wish that our friends in England could by the assistance of some magical spying glass take a peep at our situation: Dr Solander setts at the Cabbin table describing, myself at my Bureau Journalizing, between us hangs a large bunch of sea weed, upon the table lays the wood and barnacles; they would see that notwithstanding our different occupations our lips move very often, and without being conjurors might guess that we were talking about what we should see upon the land which there is now no doubt we shall see very soon.”

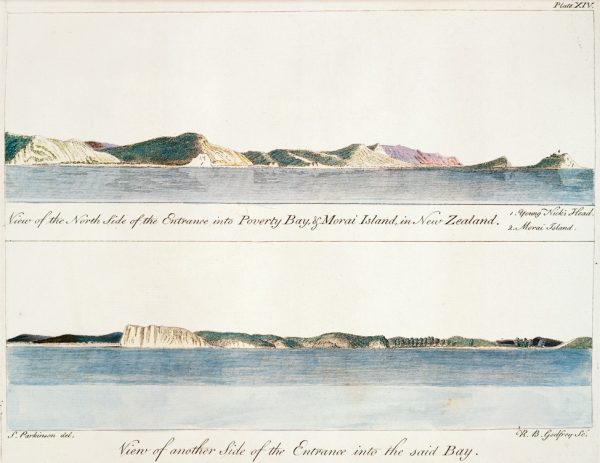

Both the amount of seaweed and number of seabirds indicated that land must be close. Nicholas Young, the 12-year-old lookout, was the first to sight it. On October 6, Endeavour sailed to the north of the Poverty Bay headland that would henceforth bear the lad’s name, and entered a wide open bay.

Two days later, canoes were seen in the bay but they soon returned to a cluster of dwelling places ashore “low but neat” where “a good many people were collected who sat down on the beach seemingly observing us”. Banks clearly did not know what to make of the pa. “On a small peninsula at the NE head,” he describes, “a regular paling, pretty high, inclosing the top of a hill, for what purpose many conjectures were made: most are of the opinion or say at least that it must or shall be either [a] park of Deer or a field of oxen and sheep.”

In the late afternoon, Banks and Solander joined Cook’s shore party in the ship’s yawl, eager for a closer look at the new country. An armed guard of red-coated marines followed in the pinnace. A group of Maori melted away into the bush ahead as the yawl made a landing near an abandoned fishing camp.

Cook poked about among the fishermen’s leavings while Banks and Solander began to explore the lush coastal vegetation, filling their collecting bags with plants that were quite unfamiliar to them. Later, when they began the process of cataloguing their discoveries, they would find that many of the specimens were not just new species but completely new genera, quite unknown to European science. Soon titoki, rewarewa and tutu would acquire sophisticated Latin names—Alectron excelsus, Knightia excelsa and Coriara arborea—based on the Linnean system of classification.

However, the plant hunters were rudely awakened from their botanical reveries by the sound of gunfire. Hurrying to rejoin Cook, they were alarmed to find that the yawl was no longer where they had left it. They made their way on foot back to the beach, where a distressing scene awaited them.

A man lay dead on the shore, one of a small group of warriors that had launched an attack on the four young ship’s apprentices.

The marines were alerted by the commotion. As the lads began to row to safety, and just as the leading warrior was about to launch his spear, he was shot through the heart by the boatswain. His kinsmen dragged the body for some distance, before retreating into the bush. This was the first time the warriors had seen white men, and the result, a chilling echo of Tasman’s fleeting experience in New Zealand, set an ominous course of relations for the two cultures.

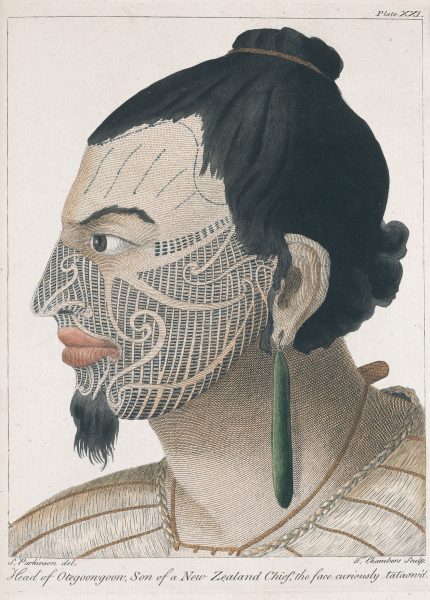

Banks recalled the dead man with forensic attention to detail: “a middle sized man tattowed in the face on one cheek only in spiral lines very regularly formed; he was covered in a fine cloth of a manufacture totally new to us, his hair was tied in a knot on the top of his head but with no feather stuck in it. His complexion brown but not very dark.”

However, this description gives no indication of the emotional impact that the bloody event had on Banks. His journal was no private diary but a historical record to be handed over to the fellows of the Royal Society for scrutiny at journey’s end, so he rarely wrote with emotional liberty. The events that unfolded over the subsequent 24 hours, however, would test his professional reticence to breaking point.

The following morning, Maori and Europeans confronted each other across the Turanganui River. This time, Banks’ friend Tupaia was at his side. The Moorean called across to the Maori gathered on the far bank and, to the Europeans’ surprise, it was apparent that his words had been understood. Tupaia promptly became the expedition’s chief spokesman.

One of the warriors began to wade across the river but stopped near a large boulder, Toka-a-Taiau, where he beckoned to Cook.

The captain responded and the gap between these two envoys narrowed until nose to nose, they shared a breath. It was enough to encourage the warrior’s kinsmen to cross the river and join Cook’s shore party.

Everything seemed to be going well enough, though Banks observed that the Maori seemed much more interested in guns and swords than in the iron nails and bits of cloth that the explorers had brought as gifts. By now more than 20 warriors, armed with spears and patu, were crowded around. If they had a mind to it they could have split a dozen British skulls before the marines with their regulation flintlocks had lifted weapons to fire, but cautious curiosity prevailed.

Suddenly, someone made a grab for the short sword hanging from the astronomer’s belt. Banks was the first to respond. As a keen sporting shooter he was as accurate as any of the marines and quicker. His musket was loaded with small shot used for collecting birds and small animals, and in circumstances such as he now found himself in, the use of small shot was the kind of controlled response to aggression that would be seen as permissible under the Royal Society’s guidelines. But events rapidly overtook such niceties of judgment. Predictably, Banks’ weapon had little effect on the retreating warrior. The surgeon was next to fire. His weapon was loaded with ball, and the running man fell dead in his tracks. In the uproar that followed, more shots were fired and the Maori retreated. Before ordering a return to the ship, Cook marched the marines across to a bit of raised ground. The union flag was hoisted and he took formal possession of the new country for King George III of England.

Later that day, three young fishermen were abducted from their canoes. Once aboard, Cook had thought to win them over with a demonstration of hospitality and goodwill, but tragically four of their compatriots were killed in the kidnapping.

This bungled attempt at commando diplomacy seems to have been the last straw for Banks. For once he allowed himself to express strong personal feelings in his journal, and the entry for October 9, 1769, reveals real anguish at the violence:

“Thus ended the most disagreeable day my Life has yet seen,” he says, “black be the mark for it and heaven send that such may never return to embitter future reflection.”

As for the young hostages, Endeavour must have seemed as unfamiliar as a spaceship, its inhabitants aliens—except for Tupaia. The Moorean was able to comfort them and they were soon displaying a hearty appetite for salt pork and ship’s biscuit. The next morning, they were in good spirits when they accompanied the expedition shore party, calling out to their kinsmen gathered on the far bank of the Turanganui that they had been well treated and had met a great man who was almost one of their own. Tupaia’s mana had come to the aid of Cook’s commando diplomacy. Eventually, an elder waded across the river and presented Tupaia with a green bough.

Despite the uneasy truce that ensued, there was to be no more botanising for Banks. On October 11 he wrote, “This morn We took our leave of Poverty Bay with not above 40 species of plants in our boxes, which is not to be wondered at since we were so little ashore and always in the same spot.”

Cook needed to find a more welcoming anchorage for the supplies of fresh food and water his crew so badly needed. As Endeavour sailed on there were frequent encounters with Maori—often hostile. In a typical encounter, Maori would perform a blood-curdling haka, often followed up with spears and stones, which would come rattling off the sides of the oak intruder. Sometimes Tupaia’s diplomacy, supported by a demonstration of Endeavour’s superior firepower, would ameliorate the aggression enough for a little trading to occur. But misunderstandings frequently arose over the exchange of goods and the consequence was often more Maori deaths and injuries.

However, on October 21, 1769, Endeavour arrived at Anaura Bay, where Banks’ journal refers to extensive Polynesian gardens, “the ground tilled that I have seldom seen land better broken up”, where were planted “sweet potatoes, cocos, and a plant of the cucumber kind, as we judged from the seed leaves which just appeared above ground”. These plantations varied in size from one to 10 acres and, as he records, “each distinct patch was fenced in, generally with reeds placed close one by another, so that a mouse could scarcely creep through”. In total, there were between 150 and 200 acres under cultivation at Anuara Bay, “though we did not see above 100 people in all”.

It was also here that the Banks and his companions collected their first specimens of puriri, the tree sometimes called New Zealand teak. His journal also describes the gardeners’ latrines and dunghills, far superior to the deficient hygienic arrangements seen in Tahiti. The womenfolk, however, were found to be less amenable to the explorers’ advances and he describes them as being “as great coquettes as any Europeans could be and the young ones as skittish as unbroke fillies”.

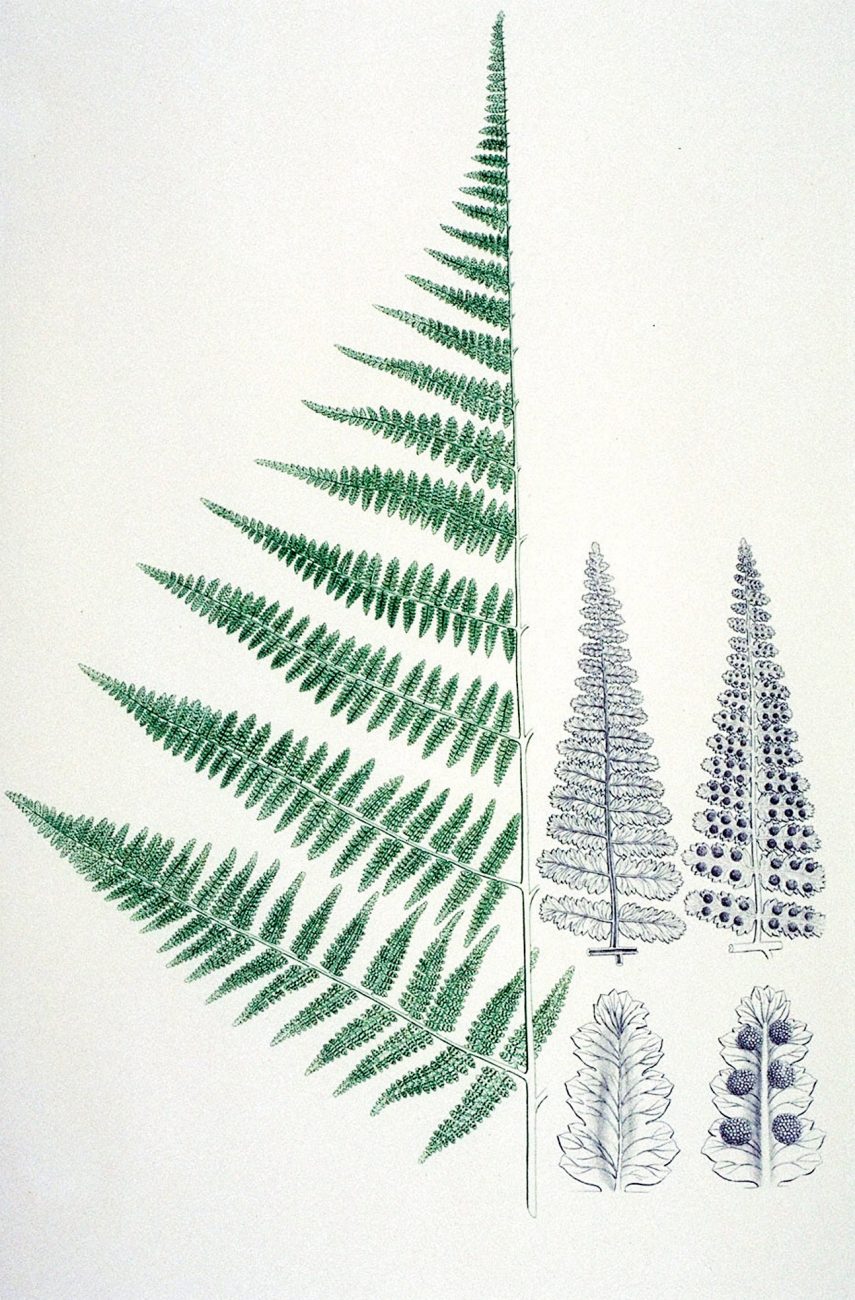

It was early in the growing season and fresh vegetables were still in short supply, but Banks noted that people filled the gap by eating the roots of bracken fern, or as he knew it, “Pteris crenulata, very like that which grows upon our commons in England”. The roots were first roasted and then beaten with a stick to remove the tough outer layers. Someone handed him a charred tidbit to try and he found that it had “a sweetish clamyness not disagreable to the taste”. The downside were the fibres which, “in quantity 3 or 4 times exceeded the soft part; these were swallowed by some but the greater number of people spit them out for which purpose they had a basket standing under them to receive the chewed morsels, in shape and colour not unlike Chaws of Tobacco”.

The following morning, a heavy swell obliged Cook to seek a more secluded anchorage a few miles to the south, now known as Tolaga Bay. Cook’s name for it may be a corruption of “turanga”, a landing place.

According to Sydney Parkinson’s diaries, he, Banks and Solander roamed among “hills covered with beautiful flowering shrubs, intermingled with a great number of tall and stately palms which fill the air with a most fragrant perfume”. With proper cultivation, he proclaimed, this landscape could be “rendered a second kind of Paradise”. Banks and Solander discovered many new specimens here including whau (Entelea arborescens), milk tree (Streblus banksii), ake ake (Dodonaea viscosa) and the white sun orchid (Thelymitra longifolia), and also made reference to an abundance of parrots, pigeons and quail. Banks was surprised at the lack of four-legged animals apart from Polynesian rats (kiore) and dogs (kuri). He described the latter as “very small and ugly”, like the ones he’d seen in Tahiti.

He was also entranced by a natural rock archway that framed a gorgeous view of the bay. “So much is pure nature superior to art,” he declared in the journal. Maori, being less susceptible to the romantic notions of a European sensibility, named the archway Te Kotore o te Whenua, “the anus of the land”.

Endeavour sailed on into the Hauraki Gulf where, on the morning of November 19, 1769, two canoes came out from the shore. Tupaia was greeted by name—the Polynesian’s mana evidently having preceded him. The following morning, Banks joined Cook in the pinnace as the Maori led the way up the Waihou River until a magnificent kahikatea forest closed around them. The botanist was overwhelmed, “the banks of the river were cloathed with the finest timber my Eyes ever beheld. Every tree as streight as a pine and of immense size…”

On felling one of the smaller trees, he noted the timber to be extremely dense and heavy, and would “make the finest Plank in the world”. This was, he declared, “the properest place we have yet seen for establishing a Colony… The Noble timber, of which there is such abundance, would furnish plenty of materials either for the building of defences, houses, or Vessels.”

He described the Waihou as being “as broad as the Thames at Greenwich”, and Cook was so taken with the comparison that he renamed it accordingly. In January the following year, the ship ran down the west coast where Cook, wary of prevailing westerlies, allowed it to approach the shore only as close as efficient cartography required.

As the boat made a landing at Ship Cove (Meretoto) in Queen Charlotte Sound, a group of Maori disappeared into the forest. Driven by curiosity, they soon returned to find the visitors examining the remains of their camp kitchen. Banks had noticed that one of the provision baskets held some bits of meat and a couple of longish bones “pretty clean pickd…and on the grisly ends which were gnawed were evident marks of teeth”. Although Banks was aware of the existence of cannibalism amongst the Maori, he was “pleasd at having so strong a proof of a custom which human nature holds in too great abhorrence to give easy credit to”. With Tupaia interpreting, he learned that the bones were those of an enemy, one of seven killed in a recent skirmish.

It was also while anchored in the Sounds that he was moved to write those words that have become emblematic of New Zealand’s lost dawn chorus. His description of being “awakd by the singing of the birds ashore…their voices were certainly the most melodius wild musick I have ever heard, almost imitatting small bells but with the most tuneable silver sound imageinable”.

After being re-caulked and repaired, Endeavour sailed out of Queen Charlotte Sound on February 6 and, over the next three months, completed a clockwise circumnavigation of the South Island. Cook’s reluctance to make any further landfalls frustrated Banks. But an even greater disappointment assailed him. He had been clinging to the hope that New Zealand would turn out to be an outpost of a vast, undiscovered southern continent—a notion that the expedition’s sponsors had also cherished. There were many aboard who were sceptical, including Tupaia, who had never heard of any great southern landmass. When Endeavour rounded Stewart Island’s South West Cape, Banks’ fervent hopes of discovering some kind of land bridge linking Terra Incognita Australis to New Zealand were finally dashed. The “no Contineters”, as he called them, celebrated by roasting a dog, and with admirable culinary economy the offal was made into a haggis.

[Chapter Break]

Banks’ visit to New Zealand is recorded in his Account of New Zealand, which includes detailed observations of Maori apparel, cooking methods, weaponry, fortifications and much else which represents a valuable record of a way of life that history obliterated. He admired Maori skills in boatbuilding, carving, gardening and fishing. He was frank about those aspects of the culture he found harder to accept—such as cannibalism.

But the greatest legacy of Joseph Banks’ visit to these islands are the many New Zealand plants that he collected and described with the assistance of Daniel Solander—almost 400 of them and all but a handful species that were new to science. His Florilegium, a portfolio of 743 of more than 3000 plants he and Solander collected during the Endeavour’s three-year voyage of discovery, took five artists and 18 engravers to complete and wasn’t even printed within his lifetime.

One of the most striking illustrations is Sydney Parkinson’s representation of harakeke, the New Zealand flax—a souvenir of the six months that the Endeavour spent in New Zealand waters. Banks wrote, “Of the leaves of these plants with very little preparation all their common wearing apparel are made and all strings, lines and cordage for every purpose, and that of a strength so much superior to hemp as scarce to bear a comparison with it. The Finest cloaths are made with the extracted fibres, snow white and shining almost as silk and likewise surprisingly strong.”

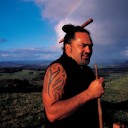

Freshly returned from his voyage to the ends of the Earth, Banks had his portrait painted by society artist Benjamin West. In it he wears a flaxen cloak whose qualities he seems to be recommending.

The cloak and the other items he has chosen for his backdrop suggest a lasting regard for New Zealand, for its unique plant life and the culture of its first people.

But looking out over the Hauraki Plains it’s now hard to imagine that great kahikatea forest that so overwhelmed him. The swamps that he enthusiastically recommended “might easily be drained” have been, and like variegated ants, great herds of cattle swarm across the green baize of the vast snooker table we swapped it for.

From Gisborne’s Cook Plaza, Young Nick’s Head is about the only thing in this landscape that the botanist would recognise today. The hills are threadbare and the mouth of the Turanganui River, where he first landed, has been re-engineered as a concrete chute. Toka-a-Taiau, the sacred river boulder where Captain Cook became the first white man to exchange breath with a New Zealand Maori, has vanished—blasted by the Marine Department to clear the channel into the harbour in 1877.

We are sceptical now of the Enlightenment notion of Progress that Banks so cherished. But there is some evidence that even he had developed some misgivings, regretting, for example, his part in the destruction of his native Fens—that vast wetland, equal in size to Hauraki, that had once been so full of birdlife that it was known as “the aviary of England”. In an elegiac poem, The Mire Nymph, written towards the end of his life, he seemed to mourn the passing of that wild watery world where he fished and hunted as a boy, nurturing a growing passion for botany along its unkempt byways.

Large parts of the Fens are now being reclaimed for wildlife, and European cranes are breeding for the first time in two centuries, reflecting a similar history of destruction and restoration that occurred at the hands of European pastoralists half a world away. If Banks were to revisit Meretoto, where the forests so enthusiastically felled for grazing are regenerating, he would marvel once more at the “melodius wild musick” of bellbirds and tui to which he awoke one morning 240 years ago.