Island of dreams

Raoul Island is a bewitched Pacific paradise which has lured to its shores a long line of would-be settlers over the past 1000 years.

Ducking as a sheet of ocean is punched into the air by the frigate Southland, I weave my way along the rolling deck to the stern, where the ship’s wake boils through an angry sea.

An hour ago the captain pushed Southland to 25 knots in response to a Mayday call from the stricken yacht Solano near our destination, Raoul Island, 200 kilometres to the north.

Now, even as I gaze at the surging mass of turbulence below, these same huge seas are hurling Solano ashore at Hutchison Bluff, the western extremity of the island.

Clutching a deck rail, a man struggles out of his trousers, forgetting that he has put $300 into the pocket for safekeeping. As another five-metre wall of water foams towards him, he pulls on a diving mask and leaps after his companion into the sea. An eternity of seconds later, gulping salt water and fear, he is tossed ashore on to jagged rocks. A hand grabs his collar and drags him, gasping, away from the sea.

The man collapses, exhausted, and pulls off his flooded face mask. His fingertips are surprised by the familiar smooth curve of his glasses, still wedged inside the mask. They are the only things he has saved from his yacht.

I land at Raoul the next morning with a group of scientists and Department of Conservation (DOC) staff for a six-week stay. My legs welcome solid earth after two cramped days of naval accommodation.

As the buzzing Wasp flits back to the frigate for its eighth load of supplies for the island, I exchange greetings with Raoul’s residents: an unshaven four-man DOC team.

In the shade of a pohutukawa tree some distance away, a man wearing glasses, his arm in a sling, stands beside a woman with a young child wrapped around her neck. I walk over and introduce myself, and Derrick Chesterton tells me about the wrecking of his 24-metre yacht, his dream home for 15 years.

“What’s done is done,” he sighs, grateful to still be alive, and that his two grandchildren were safely ashore at the time of the grounding.

I lug my heavy dive bag along a track that leads to “The Hostel,” a cluster of white weather-board buildings that was built as a radio station in 1940 to supply weather reports to flying-boats shuttling between New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. A bright red parking meter stands next to a yellow “Taxi Stand Keep Clear” sign—an incongruous sight among the pohutukawa and ngaio of this “one-tractor town.”

“This is all that I saved,” says Northland farmer Bruce Leaf, the other crew member of Solano, sitting on the hostel’s verandah. The contents of his wallet are spread over a coffee table to dry in the morning sun. Over tea and gingernuts, Bruce tells me in almost disbelieving tones of the last ten days aboard a leaking boat in a cyclone, and of the rescue by helicopter.

His gaze wanders out past banana trees at the edge of the lawn, past the cliff edge to the broad expanse of blue Pacific beyond. Far off-shore, the last vestige of Cyclone Lisa lifts a patch of white spray in sardonic farewell.

Northernmost and largest of New Zealand’s subtropical Kermadec group, Raoul Island lies 1000 kilometres north-east of New Zealand, midway between Auckland and Tonga. A rocky coastline with sea cliffs up to 250 metres high surrounds most of the island, but within this unwelcoming exterior lie the lush pohutukawa and nikau palm forests of a nature reserve that covers the island’s 3000 hectares.

Wisps of steam still rise from a gaping volcanic caldera in the centre of the island where three lakes lie in the craters of past eruptions. Fumaroles spitting scalding water, cave walls covered with sulphur sculptures, frequent earthquakes—these are constant reminders that the island is an active volcano.

Raoul is part of a volcanic ridge which stretches south through the Rumbles—a group of submarine mountains off the Bay of Plenty coast—to Rotorua and Tongariro National Park, and north to Tonga’s active volcanoes.

The island’s vegetation reflects its transitional position between New Zealand’s temperate forests, with their tall podocarps and beeches, and the riotous tangle of palms, shrubs and large-leafed trees which clothe tropical islands.

Here, the largest trees are spreading pohutukawa—not the New Zealand “Christmas tree” Metrosideros excelsa but an indigenous species, M. kermadecensis, which flowers throughout the year.

Mahoe, hutu, mapou, ngaio and karaka are also common, but it is the palms which give Raoul’s forests a distinctly tropical look. Nikau are everywhere, their glossy dark leaves forming cathedral-like arches in the bush. In some parts of the island they form almost pure stands. There are no coconut palms, though; Raoul is too far south of the Equator for this tropical trademark to survive.

Luxuriant and green as they are, Raoul’s forests are almost silent. The birds which would otherwise fill this island with raucous song have largely disappeared—decimated by the introduction of cats, goats and rats.

The damage has been done in the last century-and-a-half. Goats were probably released on the island by whalers in the early 1800s. Cats are thought to have come from the same source, and Norway rats almost certainly made their way ashore from the wreck of the schooner Columbia River in 1921.

These three mammals are a lethal combination on islands with large bird populations. Rats eat the eggs and chicks, cats prey on the adults, and goats thin out the vegetation, making ground-feeding species more visible to predators. Kiore, the small Pacific rat, probably introduced to Raoul 500 years ago by Polynesian voyagers, adds to the carnage, taking insects, plants and small birds.

Gone are the days when visitors to Raoul could report flocks of seabirds “blackening the skies.” Apart from a 40,000-strong colony of sooty terns which still manages to breed in Denham Bay despite heavy predation, tui, kingfishers, starlings, thrushes and blackbirds are virtually the only birds that remain on the island.

In 1908, biologist Reginald Oliver recorded Kermadec petrels “nesting in hundreds of thousands” on Raoul. Today, the predator-free Meyer Islands, a pair of islets two kilometres off Raoul’s northern coast, are one of their last remaining refuges.

[Chapter-Break]

A yellow inflatable scrunches softly into a rock platform and I scramble on to the Meyers, making use of giant Kermadec limpets as footholds.

Here is life as it should be on Raoul—or in New Zealand, for that matter. A shallow rock pool brims with sprat-sized fish. A purple rock crab, clearly unused to human disturbance, scuttles around the pool looking for cover. Nearby, a pair of red-headed lime green Kermadec parakeets notice my presence, hop a few centimetres further away, then cheekily continue their foraging on a bed of ice plant.

As the drone of the outboard recedes, a city-like din of tens of thousands of bird calls takes its place. Petrels, shearwaters, grey ternlets and the occasional red-tailed tropic bird swoop and wheel, shrieking their arrivals and departures from the colonies.

The burrows of black-winged petrels and wedge-tailed shearwaters pepper the islands like holes in a Swiss cheese. In between, an egg, a fluffy chick or a parent Kermadec petrel sits on every available space.

I climb the hump-backed island carefully, mindful that a single careless step could crush an egg or collapse a burrow. Most of the petrels are asleep; they don’t even stir when I step over them. Those that aren’t, squawk at me with their strange call, a siren followed by a yodel: caaaaaw-woodle-woodlewoodle.

As I peer over rocky ledges I come face to face with grey ternlets, diminutive dove-grey birds with black “eye shadow” that makes their eyes look larger than life. They patter about on pink webbed feet, lift off briefly into the wind, then settle again.

[sidebar-1]

From the ridge, I look out across the blue expanse of the Pacific to the north. This is the end of New Zealand. The tiny lava stacks of Nugent and Napier Islands, 100 and 300 metres across, are New Zealand’s northernmost crumbs of land, only a kilometre north of where I stand.

A few days later, back on Raoul, I take an easier walk along an overgrown track behind the hostel. Flecks of golden afternoon light shaft down through the pohutukawa canopy, scattering forest patterns at my feet. Absorbed, I emerge into a small clearing where waist-high buffalo grass, almost iridescently green, separates a dozen or so orange trees from the encroaching forest. Despite their unpruned, unkempt appearance, the leafy tops of the larger trees are heavy with fruit.

These trees are around 50 years old. But not far from here, older trees, planted a century ago, still bear juicy oranges. I shake down some fruit, partially peel them and sink my teeth into the sweet centres. Wandering through this old orchard, sucking golden nectar, I think about the settlers who planted their crops, their dreams—and sometimes their very lives—in the soil of this volcanic paradise.

Raoul’s settlement goes back several hundred years before the first Tahitian orange pips were brought to the island. Back to a time when Polynesian seafarers were ranging widely over the Pacific. Maori oral history refers to the island of Rangitahua which was used as a navigational landmark on the journey from eastern Polynesia to Aotearoa. It was here that the badly leaking Aotea canoe is said to have been beached for repairs. Two other canoes, the Ririno and the Kurahaupo, were also damaged on the treacherous shores of Rangitahua during this period of migration in the 14th century. It is possible, but by no means certain, that Rangitahua and Raoul are one and the same.

That Polynesians did live on Raoul, however, is beyond doubt. Candlenut trees, edible ti (a type of cabbage tree) and kiore are evidence of their presence, as were several adzes found on the northern side of the island. According to Department of Conservation archaeologist Leigh Johnson, midden remains containing petrel, fish, seal and dog bones excavated at Low Flat “suggest an occupancy somewhere around the 13th or 14th century. A pumice layer which lies immediately above this band of material indicates that the settlement may have been terminated by volcanic eruptions.”

It was not until June 1788 that the first Europeans set eyes on Raoul Island. Sailors aboard the British ship Lady Penrhyn, which had been transporting female convicts to Australia, described a land “of considerable extent” to the north of two islands which they had named Curtis and Macauley two days earlier. Without stopping to investigate or name this island, the captain continued to Tahiti for urgent provisioning—”as the scurvy now began to make great havoc amongst the sailors,” wrote the ship’s surgeon.

Three years later, the French explorer Admiral D’Entrecasteaux rediscovered the island, naming it Raoul after one of his quartermasters. D’Entrecasteaux also gave the name L’Esperance to the southernmost rock of the group which he called Kermadec after the captain of L’Esperance, one of the ships under his command.

In 1796, Capt. Raven of the Britannia sailed past Raoul. The island was not marked on any of his British charts, so he named it after the day of his visit: Sunday. It was by this name that Raoul became commonly known until the early 20th century.

As the 18th century came to a close, the first whalers began cautiously venturing into the south-west Pacific. At the Kermadecs they struck oil—sperm whale oil—for the islands lay within the seasonal migration route for these creatures as they travelled between the central Tasman Sea and the seas around Tonga and Fiji. Southern right whales were also taken from an area to the east of the Kermadecs.

Over the next 30 years the “French Rock Ground” developed into the most prolific whaling ground in the South Pacific. Sunday Island, being a source of fresh water, firewood and meat (from the goats and pigs which the early whalers introduced), soon became a well known anchorage. By the 1830s, between 50 and 100 American whaling ships were working the area, in addition to those flying British, Australian and French flags.

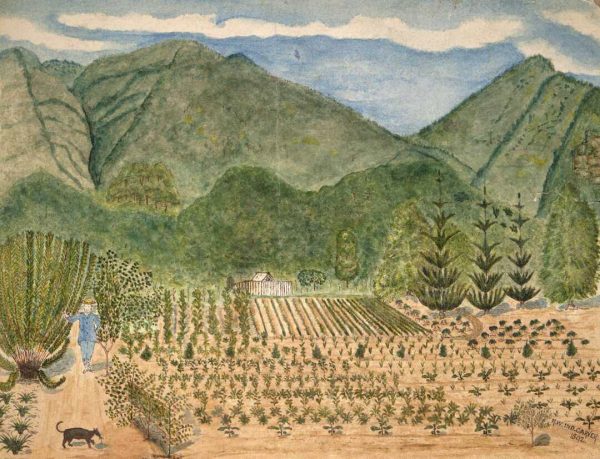

In 1836, Raoul’s first settlers, Englishman James Reed, his Maori wife Ekaumoenga and their family, arrived in Denham Bay, on the southwestern side of Raoul, to open shop and supply the fresh produce that scurvied whalers were always so desperately short of. But it took the Reeds a full year, subsisting on mutton birds, nikau hearts, fish and goat, before they could grow enough to feed even themselves properly.

As later settlers would also discover, Denham Bay’s poor, pumicey soil, regular droughts and autumnal plagues of ravenous kiore made gardening a challenge. However, when crops eventually became established, the whalers were able to buy a wide range of fruit and vegetables, as well as preserved mutton birds, poultry, fresh goat meat and firewood from the settlement.

Another Englishman, Daniel Baker, who settled on the northern side of the island with his Samoan wife a year after Reed, fared better, but the six other groups of entrepreneurs who came and went over the next 25 years chose to live in Denham Bay, since it offered a permanent supply of fresh water and a marginally better anchorage.

By the late 1850s, the great sperm whales had been slaughtered to near extinction. Fewer whalers called in to the island, and fewer of their gold sovereigns found their way into the settlers’ pockets. For those who considered leaving Raoul in search of other fortunes, a cruel decision was made on March 15, 1863, when a black-painted barque, Rosa Y Carmen, slunk into Denham Bay. The sweaty ghost of dysentery had crept over the 290 slaves on board the Peruvian slave trader—captives from the Tokelau Islands, Easter Island and the northern Cook Islands. Before long, boatload after boatload of the sick and dying were being rowed ashore and thrown on the beach—ostensibly to “recuperate.”

The captain of the island schooner Emily, which arrived from the Bay of Islands shortly afterwards, provided this account, as witnessed by the settlers: “The first launch load that was landed consisted of fifty-three men, only three could stand of the number, three were found dead on reaching the beach and the residue were hauled out of the boat in the roughest manner to be conceived and thrown on the beach, some beyond the surf and others in it. Several were drowned where they were thrown and eighty died after landing. Some not having the strength to crawl beyond the reach of the tide were drowned . . . The dead bodies were buried on the beach, in sand, and when the tide rose and surf set in all the bodies were disinterred and strewn all over the beach and allowed to remain as the tide left them.”

One hundred and fifty slaves died in Denham Bay, along with nine settlers who contracted the disease. The surviving settlers, “motherless and fatherless children, widows and widowers” were evacuated by the Emily.

Six weeks later, the crew of the Rosa rounded up the surviving slaves, raided the abandoned settlements for meat and vegetables and left for Peru. A final tragic irony awaited them: the Peruvian authorities would not allow any of the slaves to be landed or sold.

Seven years later, in June 1870, the island’s serenity was shattered by a severe earthquake. The American whaler Ellen Goodspeed, near Raoul at the time, was shaken “as though she had struck bottom.” Off Denham Bay the next morning, the captain, Preble, saw an eruption “heaving up columns of steam and smoke to the height of 2 or 3,000 feet” and covering the sky for 80 kilometres around with thick smoke. The immense updraft from the eruption sucked wind towards the island from all directions, and Preble was forced to circle the coastline for 38 hours before finally escaping the tight fist of the island wind.

What Preble didn’t know was that a small group of settlers, fearing for their lives, were huddled in the mountains, driven there by sulphurous gases billowing out of the Denham Bay cliffs. William Covert, an American, his family and an injured sailor had to wait three months until they could be evacuated by the next ships to visit, the whalers Crowninshield and Milton.

Covert later said that during that entire period he “never cooked an ounce of food but lived entirely upon the boiled fish thrown up on the beach at frequent intervals, done to a turn by the continuous submarine explosions.”

On his arrival at Raoul, the Crowninshield’s captain found the island still “burning fearful from four different parts.” Two steaming volcanic islands over 80 metres high had formed in Denham Bay, creating a near-perfect—but short-lived—anchorage behind them. Within two years, these pumice cones had been worn away by the sea, leaving no trace.

With Raoul’s volcanic rage exhausted, the island once again fell silent. Nature’s rhythms continued unabated: oranges slowly ripened, then dropped into the long grass of untended orchards. The dark lines of Pacific swells pulsed into the bay, pounded on to the gravel beach then seethed back into the turbid depths. The scene was set for the “King of the Kermadecs” to take up his throne.

[Chapter Break]

The story of Bell, wanderer and adventurer, begins in 1854, when he left his Yorkshire home at the age of 16 for the goldfields of New Zealand and Australia. Bell eventually found his way to Hawkes Bay, where he operated a flax mill and married Frederica, the daughter of a Lancashire farming family, around 1866.

Bell’s irrepressible wandering continued, now with a wife and an ever-increasing family in tow. First to the Bay of Plenty, then to Apia, Samoa, where he bought a hotel in 1877. It was here that Bell met Chris Johnson, a one-time settler on Raoul, who told him of an uninhabited paradise where vegetables sprang up like magic.

“Listen Tom, it’s yours for the taking,” Johnson enthused. “In a few years’ time, Thomas Bell could be the best known man in the South Pacific, owner of Sunday Island and KING OF THE KERMADECS!”

Neither Bell nor Johnson, as they talked and drank amid the colonial clamour of the Apia hotel that night, knew that these very words would haunt Thomas Bell until his dying day.

A few weeks later, in November 1878, with supplies and tools loaded and the hotel sold, Frederica Bell, resigned to divine providence and yet another of her husband’s harebrained schemes, stepped aboard the trading schooner Norval, Bible clutched firmly in one hand, her husband’s in the other. Six young Bells aged between one and eleven were lifted aboard by Captain McKenzie. Sails were hoisted into the warm trade winds for the lazy south-west run to Raoul and Auckland.

Eight days later, the rattle of the Norval’s anchor chain echoed out of Denham Bay. As Frederica apprehensively surveyed the towering cliffs, Bell rowed ashore, returning as dusk fell over the island. Struggling to suppress a broad grin, he hoisted a bag of oranges on board, as if to confirm his high hopes for the family’s new life on Sunday Island, where he, Thomas Bell, would achieve his Utopian dream.

Some 80 years later, Bess, second eldest of the Bell children, would recount her memories of those years in the book Crusoes of Sunday Island. Clearly etched in her mind was the family’s first fateful day on the island. After the supplies were unloaded, Bell gave Captain McKenzie £200 to purchase further supplies in Auckland. An agreement was made that McKenzie would return to the island in three months to resupply the family—or uplift them if things went badly.

As the white sails of the Norval became specks on the horizon, Frederica kindled a fire to make scones in her camp oven, and Bell cut open a tin of flour. All it contained was a hard blue lump of mould. Cursing, he opened another tin, then another. All 12 tins were the same. The tins of cabin bread were found to be a mass of weevils and crumbs.

McKenzie had swindled them. The six months of supplies he had sold Bell were completely inedible.

With no food, Bess recalled that her father’s desperation and her mother’s Bible played a central role in their survival. The few oranges growing in the bay were soon eaten, so the family gathered whatever food they could. Mutton birds, nikau palm hearts, puha and the roots of fern and cabbage tree became staples. Fish were hooked and giant limpets collected on rare occasions when the fierce breakers in the bay subsided.

There were no goats in Denham Bay, so Bell, with his two older girls, made frequent hunting trips to the interior of the island. Each time, the trio, often weak from hunger, had to scramble on hands and knees for two hours to reach the top of the 200-metre-high Denham Bay cliffs, which, even today, with ropes, are a formidable climb. Each trip was a torment for the barefooted girls as they struggled to keep pace with their father and his iron-willed desperation to keep the family alive.

Between hunting expeditions, the girls toiled in the bay’s freshwater swamp, cutting raupo and reeds and carrying great bundles of them through snagging undergrowth to the camp, where Bell laboured beyond endurance to build a hut. Bess remembered these days as “a nightmare which went on and on, week after week, month after month, with no merciful waking . . . suffering hunger and thirst, enduring the perils of goat hunting expeditions, days of back-breaking toil and nights of woeful exhaustion.”

Rumbling stomachs cried out for the day when the Norval would return. Three months passed. Four months turned into six months. The storms of winter arrived, preceded by a plague of rats which stripped the Bells’ vegetable garden bare. Their meagre rations of food were almost gone, the rain-drenched cliffs were too dangerous to climb and the sea too rough for collecting limpets or fishing.

Huddling cold, wet and hungry in their thatched hut, Bell cursed McKenzie’s name, finally conceding that the family was marooned; abandoned on this island of despair.

He was right. The Norval never returned to Raoul Island. The captain sold the schooner when he arrived in Auckland, and sailed for San Francisco with Bell’s money, not telling anyone about the family he had left on Raoul Island.

Finally, after eight miserable months, the whaler Canton sailed past the island. Alerted by the sight of smoke from a signal fire, the ship sailed into the bay. The entire family was jubilant. They were rescued!

“Life on the island is just too hard,” Bell explained to the ship’s mate, Wilkins. The words seemed to catch in his throat as he asked, “Can you take us off?”

If Wilkins had obliged Bell’s request, the name Bell would be just one of a host of failed settlers on Raoul Island. But the whaler was headed only for the empty blue expanses of the whaling grounds to the north, and had no room for a family of eight. So the Bells remained.

Provisions from the Canton lifted Bell’s heavy heart, and gave him the strength to make a move he had long considered. The settlement was shifted from cliff-shaded, rat-infested Denham Bay to the sunny northern terraces of the island. In the next weeks, in countless loads, every possession was lugged, step by painful step, up the cliffs and over the hill to the other side. Bell even dug up the grass he had planted and transplanted it, tuft by tuft, to the terraces.

Soon, Denham Bay became merely an unpleasant memory as the gentle landscape and summer sun warmed the family’s spirits.

[Chapter-Break]

Tales of a family living on Sunday Island quickly spread among the last of he whalers. Several began to make regular provisioning stops at the Low Flat settlement, where Bell sold them bananas, pineapples, peanuts, tree tomatoes, passionfruit and a wide range of vegetables.

Obsessed by his vision, Bell and his children toiled in the gardens, despite droughts, earthquakes and fierce storms. Time and time again he restored greenness to his land. He cleared forest and planted pasture, bringing his first sheep to the island in 1883.

At about this time, Bell loaded Raoul Island’s first export shipment, pohutukawa “knees” for boatbuilding, on to an island trader bound for New Zealand. He would later export crystallised bananas, wood ear fungus and Raoul’s famous oranges.

A visitor to the island during the late 1880s recorded at least 54 species of exotic plants under cultivation by the Bells, including pawpaw, guava, custard apple, pomegranate, pineapple, mango, strawberries, sugar cane, six varieties of taro and 14 varieties of banana, as well as “ordinary vegetables in great profusion.”

He also had tea and coffee growing, and Havana tobacco—a gift from Sir George Grey, the former governor of New Zealand, with whom Bell corresponded.

With the island seemingly under his command, Bell could rightly claim the title of “King of the Kermadecs.” But in 1887, as the family (which had increased to 11) was finally beginning to enjoy the fruit of years of hard labour, a party of officials arrived on the New Zealand government ship Stella and hoisted a British flag near the Bells’ homestead. In a short ceremony, Bell’s island was annexed to New Zealand and became the property of the Crown.

Bell was beside himself with rage. The land his family had lived on for nine years had been whisked from under his feet. He voiced his concerns in no uncertain terms, but was told he would have to apply to the Minister of Lands to have his farm granted back to him.

When the Stella returned to New Zealand. a report entitled The Kermadec Islands: their Capabilities and Extent was published. Eighteen months later, subdivisions on Raoul were put up for lease, and attracted considerable interest. The “Kermadec Islands Fruit and Produce Association,” a syndicate of 26 intending settlers, bought shares in two of these leases, which covered Denham Bay and the southern end of the island. Their intention was to grow early season tomatoes and potatoes for the Auckland market.

Raoul had the appearance of an enchanted paradise when the settlers arrived in Denham Bay in mid-October 1889. Amy Robson, one of the settlers, wrote: “A mist had sprung up and covered the islands, lifting every now and then to disclose high hills covered in bush of a crimson hue . . . pohutukawa covered with blossom. The effect was charming as the mist floated up and down.”

But the enchantment was short-lived. Once ashore, the settlers found that almost all of the land that they had intended to farm was in rugged hill country. The land was “so hard and steep to get at, that none of the settlers even bothered to look,” wrote 17-year-old Alf Bacon.

Angered by the misleading way Raoul had been portrayed to them by the government and by the syndicate’s organisers, most of the settlers vowed to leave the island as soon as possible. But it was to be five long months before the next ship arrived.

Unable to grow much of their own food, many of the settlers had to rely on the kindness of the Bells, who provided sheep, flour and other necessities. Other settlers, resenting the Bells’ prosperity, stole sheep and tore down Bell’s Denham Bay woolshed for building materials. Angered by this, and by the settlers’ intrusion on to what he regarded as his land, Bell nailed a sign to a tree in the island’s central caldera area: “No person is to gather mutton birds, hunt goats or cultivate any lands not rented to them or they will be prosecuted.” Exactly how was not spelt out.

After a violent earthquake and two cyclones had destroyed what remained of the settlers’ rat-eaten crops in Denham Bay, the government steamer Hinemoa arrived to evacuate most of the settlers, and took two of the Bell children, Hettie and Mary, with them. When the last families departed two years later, Bess Bell and her young brother Thomas also left the island, hoping to find a better life in New Zealand.

Over the next few years, with his family dispersing, Bell made frequent trips to New Zealand to argue the legality of the annexation of Raoul, and to contend that the island belonged to him by right of occupancy. The government eventually acknowledged Bell’s point, but simply passed a new law to validate the previously illegal annexation.

In 1898, Bell was granted a 110-hectare freehold title to the northern terraces of Raoul. Being only one-thirtieth the area of the island, this was seen by Bell as a token gesture, and it only served to increase his bitterness. Three years later, he sold the land and moved back to Denham Bay.

New huts were built and new gardens dug, but Sunday Island had not yet finished with the Bells.

In April 1910, a fierce cyclone and waterspout flattened the settlement, burying the gardens under five feet of rocks, logs and mud, and washing a boat shed and storage huts out to sea. It was too much for the beleaguered Bells, and at a family conference the unanimous decision was “Off first trip!”

Thus, the story of “The King of the Kermadecs” concluded just as it had begun: a family huddled beneath the dark Denham Bay cliffs, with little food or shelter, praying for the arrival of a ship.

That ship, the government steamer Tutanekai, arrived 12 months later. Roy Bell’s diary entry for April 6, 1911, concludes: “Sunday Island has treated us very badly and I am not sorry to be leaving. GOODBYE SUNDAY!”

[Chapter-Break]

Uninhabited Islands cast powerful spells. Another whom the enchantent fell was Alf Bacon, who, having set foot on Raoul as a teenager in 1889, returned 37 years later with two fellow settlers to fulfil his island dream. The death of one of the trio from a tetanus wound in 1927 brought that attempt to an end, but Bacon later returned with two other lotus eaters, Bruce Robertson and Reg Randall, to find the peace of mind that other settlers had striven so hard for.

He writes in his diary: “Once more I was landed on my Island of Dreams . . . Away from all troubles, apart from the world, living as nature intended us to live—on the food stuffs we grew, the fish, the turtle and wild goat we caught.”

The three lived a simple lifestyle and succeeded well at it, although Randall returned to New Zealand after a year. But, as with the Bells before him, their modest survival on Raoul was interpreted in New Zealand as a life of prosperity and ease. In 1936, under the headline “An Abundance of Food,” The New Zealand Herald reported: “Few troubles concern these modern Robinsons Crusoe. The days are recorded . . . largely for the purpose of separating the Christmas holidays from the vacation which comprises the remainder of the year.”

So it was that another group of settlers, “The Sunday Island Association,” was lured to the island in August 1936. Like their predecessors, they planted crops, intending to ship produce back to New Zealand. Nine months later, the syndicate’s supply vessel, returning from her fourth trip to Raoul, was wrecked on the Coromandel Peninsula. Stranded without supplies, the group, which numbered five, was found two months later in a semi-starved condition by the government ship Maui Pomare, bringing a survey party to plan the “Aeradio” station, as it was officially known.

The syndicate members were evacuated to New Zealand, and arrived amid a storm of controversy. The Minister of External Affairs issued a statement which concluded: “I am hopeful that . . . no other members of our community will be carried away by alluring pen-pictures painted by prospectuses or agents to spend their savings on what has been proved to be a fool’s paradise.”

And no more were. Later that year, Bacon was served notice that his property was required for the radio station. Bacon, 68 years old, accepted the government’s offer of compensation, and on Christmas Day, 1937, arrived back in New Zealand on the Maui Pomare.

Although Bacon had only lived on Raoul for a total of four years, the island had occupied his thoughts for over 50, and would continue to do so until the day he died.

[Chapter-Break]

As well as bringing to an end 101 years of European settlement on Raoul, and sowing the seeds of an ongoing New Zealand government presence on the island, the 1937 survey party planted a grove of orange trees on the terraces near the Bells’ original orchard.

As the sun sinks below the horizon, I find myself in this orchard. The warm benevolence of late afternoon has faded to a grey dusk which gathers on the silent forest. In the trees, hollowed out orange skins hang like miniature jack-o-lanterns. Soon, in the dark, large rats will climb these trees to gorge themselves on the remaining fruit, leaving only the skins behind.

Fighting my way through the waist-high tangle of Thomas Bell’s accursed buffalo grass, I reach the edge of the clearing and enter the dark, brooding forest. Where earlier soft afternoon light had fallen, tree roots and sharp rocks taunt my bare feet as I stumble along a path that emerges near noisy generator sheds—the electrical heart of Raoul’s modern settlement.

[sidebar-2]

The warm lights of the hostel are a welcome sight through the trees, dispelling nocturnal imaginings. I amble through the door. A rusty fly screen slaps closed as I empty my bag of oranges on to the kitchen bench.

Checking the roast browning in the oven, and the contents of the pots simmering on top, I glance through the door to where the unshaven mob recline, eyes glued to a television radiating the tenth re-run of Mr Bean. A fluorescent tube pings overhead, and I can’t help but compare this scene with the hardships endured by the Reeds, the Bells and all Raoul’s other early inhabitants.

Certainly, the island has been subdued by technology in the last few decades. But alone in the forest a dark heart still beats. Who is to say when the volcanic bowels of the island will again belch thunder and erase this smug technological enclave from the untamed wilderness which is the real Raoul Island?

[chapter-break]

Raoul is the kind of place where you take your watch off when you arrive, and quickly get used to living within nature’s placid rhythms. But nature has been far from quiet this year.

Barry Sampson, senior officer of this year’s DOC team, was out walking when a big earthquake shook the island in early March. “It was the most amazing sensation, walking across an open paddock with the ground moving and all the trees swaying. I was airborne for an instant.

“During the morning, the quakes became more frequent and very strong-5.7 to 6 on the Richter scale. We weren’t all that concerned at first. It was a beautiful day and the island looked incredibly tranquil. The only thing was that the ground was shaking.”

Scientists at the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in Wellington noticed similarities in the seismograph readings to those made before Raoul’s last eruption in 1964, and feared that another eruption was imminent. That evening, the four staff were evacuated to a dive charter launch which was in the area at the time.

In the event, there was no eruption, and in the following months the shocks became less frequent, allowing Barry and the other staff—a mechanic, an electronics technician and a meteorological officer—to get back to their work.

Raoul, the only weather station in the empty seas to the north of New Zealand, is an important link in the global weather network, supplying information for local, global and aviation forecasts. Barry Sampson spends every third morning collating the meteorological data—including information from a daily weather balloon flight—then relays the data by radio to the MetService in Paraparaumu.

“After I’ve done the weather, I often head off into the hills for the afternoon and search a grid quadrat to see what’s growing.” Barry’s vegetation survey is part of an ongoing programme to document rare and endangered plants, and to assess the impact of introduced weeds on the island’s flora.

One duty that has taken on increased significance since this year’s earthquakes is the weekly walk over the hot earth of the central caldera to the Blue and Green crater lakes. Here, the lake level and temperature—early warning indicators of an eruption—are measured. During the March earthquakes, Green Lake, the site of the 1964 eruption, rose by almost a metre and steadily increased in temperature, fuelling fears that the earthquakes would lead to an eruption.

Sadly, a long-term resident and loved companion to island staff for the last 14 years died earlier this year.

I remember Smelly in 1991: a highly-strung Jack Russell terrier who drove everyone mad with his incessant yapping. This year, island staff knew only a dog-tired Smelly, worn out by years of excited living.

“He slept through most of the earthquakes,” Barry Sampson told me over the telephone. “But we still used him as an earthquake indicator. If he moved at all, then we knew for sure that it was a sizeable ‘quake.”

After the end of the summer cyclone season, yachts sailing between New Zealand and the Pacific Islands often call in to Raoul, bringing mail or perhaps a bottle of whisky from friends in New Zealand, or just to experience for themselves the legendary Raoul Island hospitality.

This winter has seen up to three yachts at a time anchored off the Fishing Rock boat landing on the northern side of the island.

Visitors can have their passport stamped with Raoul’s unofficial stamp before embarking on the “grand tour,” which starts with a short bush walk, then passes through workshops, the generator shed, meteorological station, past chicken coops to the orchard to pick a few of Raoul’s renowned oranges, and concludes with tea and pikelets with jam and cream on the hostel balcony.

Most of the time, though, the daily routine is about keeping tracks clear, servicing machinery, maintaining buildings and controlling noxious weeds. At the end of a hard day swinging a machete—there are a dozen or more weed species which, given the chance, would choke Raoul’s forests—there’s always a cold bottle of the local brew in the fridge. Barry says it’s just like the real thing, but adds, “one thing I’m really hanging out for, though, is a nice bottle of Cloudy Bay Sauvignon Blanc.”

To while away the evenings, staff can make use of the hostel’s library and extensive video collection, but recently Barry has been learning to play the recorder.

“One of the other guys has a recorder as well, and Steve’s got a drum kit on the island. At Christmas time, I don’t remember the particular carol, but we slaughtered it,” he laughs.

Visions of a drum and recorder ensemble grinding through ten verses of “Silent Night” ease my nostalgia for the island a little as I sign off and hang up the phone 1000 kilometres away.