Inside the alien brain

For the first time ever, scientists have recorded the brainwaves of freely moving octopuses—tracking three big blue octopuses (Octopus cyanea) through 12 hours of sleeping, eating, and swimming around a tank. Some of the trio’s brain activity patterns resembled those of mammals. But researchers also identified a long-lasting, slow oscillation that didn’t seem to match any particular behaviour and which they’d never seen before. They think it may represent memory or learning processes.

The octopus mind is an intriguing subject for neuroscientists, since the invertebrates display behaviour linked to intelligence—such as tool use, playing, and distinct personalities. Yet, the mollusc and mammal lineages split on the tree of life 1.2 billion years ago, meaning octopus smarts have evolved independently from our own. In addition to its central brain, two-thirds of an octopus’ neurons are located in its arms.

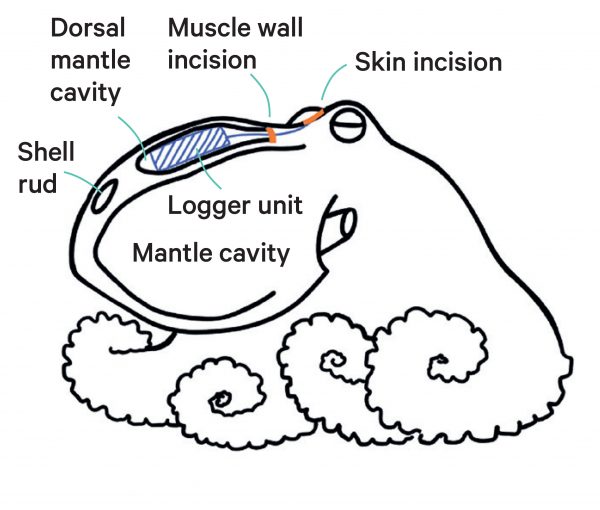

It’s these powerful arms that posed a challenge for scientists: “If we tried to attach wires to them, they would immediately rip it off,” says Tamar Gutnick, lead author of the study. Octopuses also lack hard surfaces, such as a skull, to attach electrodes to. So the research team anaesthetised each octopus and surgically inserted a data logger under its skin—out of reach of probing tentacles. Electrodes were slipped into an incision between the eyes, into the brain region thought to be important for visual learning and memory, and once they recovered, the octopuses were filmed going about their octopus business. In future, researchers plan to combine brainwave detection with learning and memory tasks, to further tease out what’s going on in their alien brains.