In debt to nature

This year, it took the human race 212 days to exhaust what the planet generates in 365.

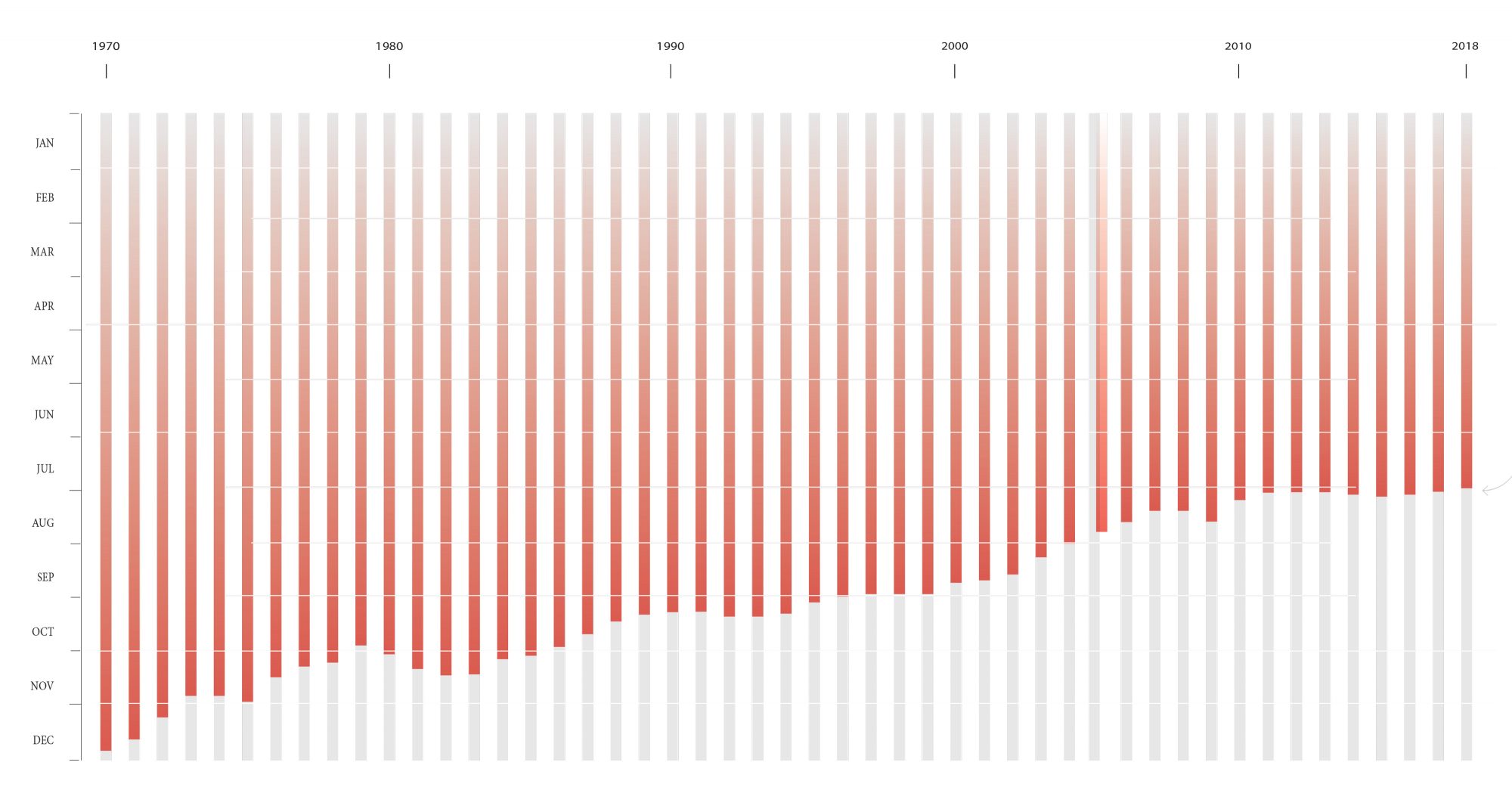

Every year, the Global Footprint Network keeps track of the natural resources we use, and plots that consumption against nature’s ability to replenish them. And every year, it marks the precise day we exhaust them with Earth Overshoot Day, when humanity tips over from the black into the red. This year, we emptied the planet’s capital account by August 1—a new record in consumption. We’re in overdraft now until New Year’s Day.

In the early 1980s, Earth Overshoot Day fell in mid-December, but we’re devouring natural resources faster than ever. This year, we took just 212 days to exhaust the planet’s annual capacity to produce food, water, fibre, land and timber.

The last time we were living within our means was the late 1960s, but the world’s population has doubled since then, and now, 86 per cent of countries use more resources than they produce.

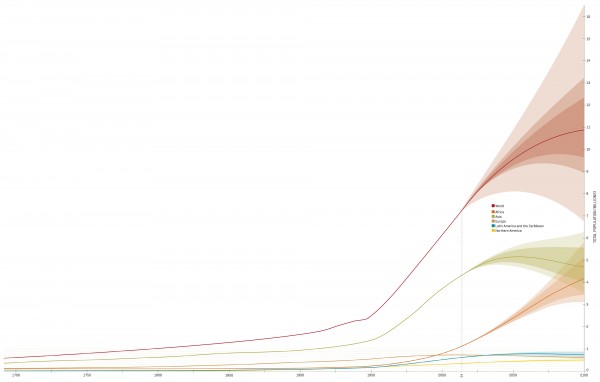

What’s driving this? Economists predict the global economy will grow by about three per cent every year this century, which involves a doubling of economic activity every 23 years. By the turn of the century, our voracity for global resources will have increased by roughly 1600 per cent.

What does this mean for the planet?

“Each successive doubling period consumes as much resource as all the previous doubling periods combined,” wrote Rod Smith of Imperial College London in a 2007 paper.

In other words, if growth forecasts are correct, come 2030 we will have used up, in 30 years, resources equivalent to everything else consumed in human history. By 2053, we will have doubled that rate of consumption again.

Most developed nations exhaust their budgets before June.

That’s the prescription for infinite economic growth. The problem is, we live on a finite planet. Take water, for example: the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization predicts that by 2025, 1.8 billion people will be suffering “absolute water scarcity”. By 2030, as many as 700 million people will be displaced in the search for adequate water, while two-thirds of the world’s population could be living with

water constraints.

But not here in Godzone, surely? For now, we still produce more resources than we consume—but that’s a happy fluke of our low population and agrarian economy.

In terms of impacts, New Zealanders are as guilty as anyone else. In 2009, researchers from Victoria University, Auckland Council and Otago Polytechnic began a three-year study into our appetite for resources. As a yardstick, they adopted the Global Hectare, a measure of the productive land and water available per person worldwide. When I was born, in 1960, I had 3.96 global hectares at my disposal. The world’s population has increased since then, so now I have 1.7 hectares.

But what I actually take is very different. By various estimates, New Zealanders use between five and eight global hectares each. If everyone on the planet lived like a New Zealander, they would need nearly three planets to sustain them (although we’re thrifty compared to the Qataris; if we all adopted their lifestyle, we would need nine planets).

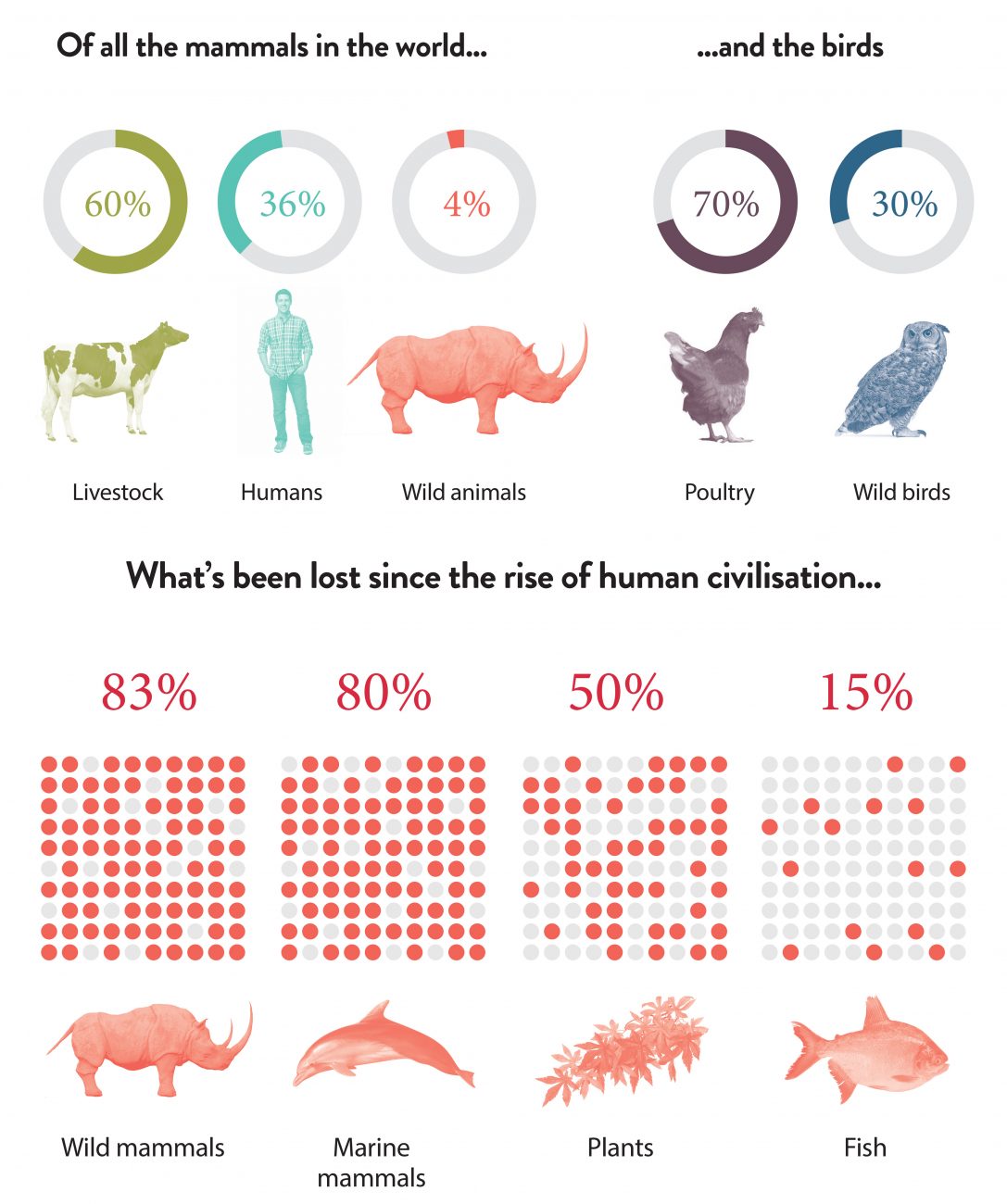

Some of that is down to the way we farm. Our intensive, industrial, irrigated model of food production runs counter to nature’s way of making land last. The ‘green revolution’ of the 1950s and 1960s, which improved agricultural technology, boosted global food production threefold, says the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, but the cost has been extraordinary. Globally, some 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil blows or washes into the sea every year, according to a recent United Nations-sponsored study, and a third of the planet’s land is now severely degraded. The global herds and flocks needed to feed humans are displacing other, wild creatures. The study found that farmed poultry makes up 70 per cent of all birds on Earth. Of mammals, 60 per cent are livestock (mostly cattle and pigs), 36 per cent are humans, and just four per cent are wild animals.

Much of that increased production is wasted. The FAO says that around a third of annual global food production, some 1.3 billion tonnes, is thrown out or left to spoil. Each year, consumers in rich countries waste nearly the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa—close to 230 million tonnes.

It’s ironic that we demand fiscal accountability from the companies we invest in, even as the planet itself is being run as a Ponzi scheme.

“We’re borrowing the Earth’s future resources to operate our economies in the present,” said Mathis Wackernagel, president of the Global Footprint Network, on Overshoot Day this year.

“Like any Ponzi scheme, this works for some time. But as nations, companies, or households dig themselves deeper and deeper into debt, they eventually fall apart.”

What’s to be done? Well, one clue lies in the fact that Overshoot Day has only ever been postponed by some global economic hit—the 2007-08 financial crisis saw it pushed back by five days. Recessions in the 80s and 90s did the same. Put simply, we need to stop buying so much stuff, using it up, then throwing it away.

We could start by changing our diets. A joint British and Swiss study published in 2018 found that meat and dairy provide only 18 per cent of calories consumed worldwide, and 37 per cent of protein, but occupy the vast bulk of farmland—83 per cent. Meat and dairy also produce 60 per cent of global agricultural greenhouse-gas emissions. By eating vegetarian for half a week, we could win ourselves another five days of balanced books every year.

The warning lights have been ignored for decades, but how long can Earth’s engine keep revving at the red line? Last year, more than 15,000 scientists from 184 countries put their name to a “warning to humanity”, published in the journal BioScience, which pointed out that environmental problems are now becoming critical. Spiralling population growth, tropical forests that are now a source of carbon rather than a sink, biodiversity loss, ocean dead zones, dysfunctional polar geosystems—all, says the Union of Concerned Scientists, are approaching tipping points, beyond which be dragons. No one really knows what will happen when fundamental physical and ecological processes fail.

The solutions are evident: restoring equality to all people—especially women in developing countries—turning off the oil tap, paying the real costs of consumption, plant-based diets, restoring biodiversity, enshrining renewables in law. Time to put away the credit card, say scientists, before the bank collapses.