Hokonui Moonshine

In the last century illegal whisky production in Southland’s Hokonui Hills was a subject of police investigations. Today that shady past is a cause for celebration.

The legend of Hokonui leads back to one family: the McRaes. After almost a century as criminals, Southland’s most famous whisky producers have emerged as folk heroes. Their story is told in Gore’s Hokonui Moonshine Museum and celebrated each year with a food and whisky festival.

The home of the McRae clan is the Kintail district, in the western Highlands of Scotland. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Highland Clearances drove thousands of Scots from their properties to make room for large sheep farms. Recently widowed and seeking better fortunes, Mary McRae decided to join her three brothers in the South Island of New Zealand. With her fours sons and three daughters, she packed up the family belongings, including a copper and brass whisky still, and sailed to Dunedin in 1872. The family settled in the Hokonui Hills, near Gore.

Whisky-making had been a Scottish tradition for generations, the earliest known distillation being recorded in 1494. In 1644, the Scottish parliament introduced a duty tax on whisky, which drove the practice underground. The term moonshine originally referred to “occupational pursuits which necessitated night work, or work by the light of the moon”. In Scotland, the McRaes didn’t view distilling and selling whisky as illegal. They thought of it more as an inalienable right. The whisky tax was considered an imposition by the English and therefore to be ignored on principle.

In the 1870s, whisky in New Zealand was imported mostly from Scotland and Australia and was frequently so watered down it was said “A dram was often offered a chair as it didn’t have the strength to stand up.”

A licence was required for brewing or distilling alcohol in New Zealand, and any sales were subject to excise tax. To the McRaes, undercover whisky-distilling was second nature and they hid their still in the creeks and gullies of the Hokonui Hills. Mary McRae had trained as a domestic distiller in Scotland, but nearly everyone in the growing local clan made whisky. Mary’s eldest son, Murdoch, was perhaps the best known. He saw distilling as a natural extension of farming.

The McRaes made whisky in time-honoured fashion, putting it through more than one distillation. Yeast and sugar were purchased from local stores, and malt was prepared in the traditional way by grinding sprouting barley into paste, although later generations found it easier to obtain it from the local brewery. The wash barrels were kept well hidden with the still. The copper condensing coil, or worm, was the most precious part of the still and was brought on site only for spirit-making.

The McRaes started selling their whisky quietly, confining their clientele to professional people such as doctors and lawyers, who were unlikely to talk. The whisky-makers had a policy of not selling their spirits “into any house where it would do harm”.

The unlabelled whisky, delivered in bottles, cans and milk billies, became known simply as Hokonui. It was said to compare with Scotland’s best. Mary McRae lived to be 94 years old, and believed she owed her long life to her regular dram.

[Chapter Break]

As the 19th century drew to a close, the issue of alcohol came to a head. The country was divided on the matter. While Presbyterians, led by Dunedin’s Reverend Thomas Burns, preached the “evils of the demon drink”, others—often Catholics—were equally passionate about their right to enjoy a tipple. In the introduction to the book Temperance and Prohibition in New Zealand, the Reverend J. Cocker writes: “In the year 1890 a flame of great enthusiasm swept through the land from North Cape to Bluff. A breath of God moved the people. Prohibition became the burning question of the day. The blood of the reformers was hot.”

The prohibitionists launched a vigorous campaign, employing slogans such as “The house of God is built upon a rock, not a vat” and “The Barrel or the Boy—you must decide.”

Gore’s papers were also spilt. The Mataura Ensign was sympathetic to local drinking establishments and carried advertisements for the district’s hotels, while the Southern Standard maintained a pro-temperance stance. The debate raged around the country. Public temperance meetings were regularly held and as regularly disrupted by publicans and their supporters. In 1894, the Clutha licensing district was the first to make the sale of alcohol illegal. The Mataura district, which included Gore, followed suit in 1902, when 60 per cent of residents voted in favour of prohibition.

Lamenting this turn of events, one Model T Ford was famously painted with a skull and crossbones. The words “Gore’s Departed Spirits—Gone But Not Forgotten” hinted at the underground moonshine trade.

In the Mataura district, 15 licensed hotels had to close their doors. But that’s not to say there wasn’t any drinking. Buying and selling alcohol was illegal, but drinking it was not. Just 18 km from Gore, the Mandeville Hotel, in the unrestricted Wakatipu district, did a roaring trade—as did the local taxi services.

So-called keg parties became popular. Lads would pool their money and send one person to a nearby licensed district to buy as much booze as the money would cover. They would then proceed to drink the whole lot in one sitting.

Making beer wasn’t illegal in Gore either, as long as the brewer was licensed and paid customs tax. While the rest of the town ran dry, production at the local brewery continued uninterrupted. The beer was taken to a depot outside the district, 18 km from town.

Hokonui became the common name for illicit whisky right across Southland. Prohibition strengthened the market; war and depression increased demand further. The number of stills grew.

Gore district arts and heritage curator Jim Geddes says there were two types of Hokonui: the old Hokonui—the high-quality product of the McRae clan—and the substandard spirit produced in rudimentary stills, often constructed from 44-gallon drums.

“For the old McRaes it was a cultural thing,” Jim says. “It was something that had been passed down by their ancestors. For others, it was purely a money-making thing. Some people deliberately flouted the law, but the old McRaes didn’t. It wasn’t so much that the McRaes were out of step with the law as the law was out of step with them.”

Hokonui became highly sought-after by the region’s drinkers, and the moonshiners became highly sought-after by the law. There are many stories of law evasion in the Hokonui Hills. One officer stationed himself outside the McRae home, hoping to overhear details of the secret distilling locations. But the family spoke Gaelic at home and the officer went away none the wiser. Another story concerns a visit to Mary McRae from an Invercargill constable. Mary is said to have hidden a barrel of whisky under her full skirts. On yet another occasion, police arrived to find the old lady in bed. What they didn’t find were the stoneware jars of whisky her sons had hurriedly put under the blankets with her a few seconds before.

Sometimes the law won. After one raid, the police approached a farm worker and requested his help removing the stills. In giving it, he led them to a second still site. When whisky was seized and poured out, customs officials were known to request those present to “Tip your hats to farewell departing spirits.”

Hugh Sherwood Cordery was the collector of customs in Invercargill between 1928 and 1935. A teetotaller, he made prosecuting illegal distillers, particularly those producing dangerous brews, his personal mission. He pioneered the use of an aircraft to find stills and took along his own box Brownie camera to record his findings. Yet he occasionally struggled to secure prosecutions with Southland juries reluctant to convict McRaes. He succeeded in driving a small number of errant distillers from the district, but most of those who were convicted paid their fines and returned to their farms.

The last prosecution for illegal distilling was in 1957, three years after the repeal of prohibition. Gerald “The Major” Enright of Timpanys near Invercargill was one of the few moonshiners who continued distilling after prohibition had ended. He had a huge illegal distribution network that stretched from Invercargill to Christchurch. In 1950 he had been caught and fined and his distilling equipment seized. The police didn’t destroy the still, however, but sold off the components at an auction house in Invercargill. Enright’s friends were the successful bidders. When he was caught again, he was charged not only with illegal distilling but also with using seized equipment. This time his punishment carried a jail sentence.

[Chapter Break]

Details of more than 30 prosecutions are on display at the Hokonui Moonshine Museum in Gore, thanks in part to Cordery’s grandson, Sher‑wood Young, a police historian in Wellington who donated images from his grandfather’s personal collection. The museum opened in 2001, bringing Gore’s illicit past out of the closet and preventing the story from disappearing into legend.

“There was no material in any local archives that related to Hokonui,” says Jim. “We had to start from scratch. The Distillation Act had only been officially relaxed a few years earlier so people were still a bit reluctant to talk about it. We had to tread very carefully.”

Heritage officer Sue Wilson spent four years collecting information for the museum. She started with official records of prosecutions at Archives New Zealand and then worked with police, customs and temperance groups. She tracked down descendants of Mary McRae and recorded the stories of old-timers who had been around during the moonshine era.

Together, Sue Wilson and Jim Geddes fleshed out the history of Hokonui, converting an oral collection of myths and tall tales into a full and factual record. They verified some of the popular stories, such as the one about a man in Gore who used to operate a still in the back of a wash house. When the still exploded, his wife was badly burnt and taken to hospital, where it was explained to the doctor that she’d sustained the burns while making jam. The doctor knew better and gave the couple 12 hours to get rid of their still before he called the authorities.

The Hokonui story was saved just in time. Many of those who shared their memories with the museum have since died. But the tale continues to unfold. Bottles of Hokonui turn up every now and then in farm sheds and attics, and people continue to come forward with stories.

“We just got something in the mail the other day,” Jim says. “A man who was a top-dressing pilot in the 1950s sent a reminiscence of coming across some Hokonui in the back of Mandeville.”

Another boutique distiller, Malcolm Wilmott, was lucky enough to buy a bottle of Hokonui in 1953, when prohibition was still in force. He went on to make his own whisky, first illegally and now legally. “I’ve been quietly distilling for 45 years,” he says. “It was illegal so it had to be fun.”

What started out as a handy fund-raiser for his flying club soon developed into a career. As well as making whisky, Malcolm designed stills. When the Custom Distillation Act was repealed in 1989, Malcolm teamed up with chemist Peter Wheeler to form Spirits Unlimited, which produced home distillation equipment. The two went on to start up The Southern Distilling Company, a legal and licensed spirit manufacturer that now makes Old Hokonui whisky to the original McRae recipe, taken from a document handwritten by a relative of the McRaes and now displayed in the Hokonui Moonshine Museum.

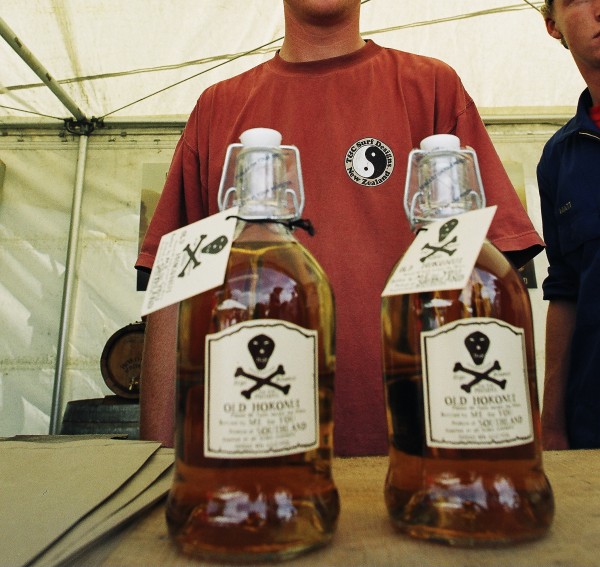

Old Hokonui is a pale whisky with a smoky finish. The Southern Distilling Company also makes a liqueur, which is a blend of Old Hokonui, manuka honey and wild Southland mint. Both the whisky and the liqueur are sold in stoppered bottles with a skull-and-crossbones label. The pirate emblem was originally used on moonshine made by Gerald Enright. The slogan beneath it reads: “Passed all tests except the police”. This is a reference to Murdoch McRae’s whisky, which was given rave reviews by a testing panel at the 1925 Dunedin Exhibition.

Old Hokonui is sold at the moonshine museum and is the focal point of the annual Hokonui Moonshiners’ Festival, held in February in the town’s historic precinct. New Zealand’s only whisky and food festival, the event is a day-long celebration of the region’s colourful past.

To the accompaniment of the Warratahs and the Half-Naked Bush Poets, 1200 festival-goers sample possum and rabbit pies, venison salami, scallops, seafood chowder and, of course, whisky. Samples of Old Hokonui are poured by still-master James Stenton, who started making whisky before he was old enough to drink it. The 22-year-old has been working for Southern Spirits since he was 17.

Next to the tasting booth is a working model of a traditional still. Peter Wheeler explains the whisky-making process. First, barley is germinated, in the course of which starch grains are converted to sugar. The sprouting grain is then ground into malt paste, which is rinsed with increasingly hot batches of water to dissolve out all the sugar. Yeast is added to the liquid to convert the sugars into alcohol.

Distillation is the process of separating alcohol from water. The fermented mixture is heated and, because alcohol boils at 80° C and water at 100° C, the alcohol evaporates first. The alcohol vapour rises into the neck of the still and then into the coiled length of pipe called the worm, where it cools and condenses into a clear liquid—more or less pure alcohol. Water is used to dilute the alcohol to 64 per cent proof, and this mixture is then fermented in wooden barrels, these days for at least three years. The amber colour of the finished product is imparted by the wood. Wheeler offers a sample of the raw alcohol, which drips from the replica still. We knock it back and then exhale dramatically. The name firewater is well deserved.

The legend of Hokonui runs deep, and nearly everyone in Gore has a story to tell. Geoff Roughan owns Southern Salami. He processes wild game from the Hokonui Hills for local hunters and is selling farm-raised-venison sausages at the festival. He remembers when he first heard about Hokonui moonshine: “When my family shifted to Gore 30 years ago, the elderly neighbour behind us told stories about when he was a boy and had the job of delivering jars of moonshine to certain clients—part of his so-called apprenticeship.”

Peter and Beverley McDonald, of Gore’s Table Talk Café, get into the spirit of the Hokonui era by dressing in turn-of-the-century costume. Their possum pies and whisky-andmaple lamb-burgers are a festival hit and the couple are enjoying the day.

“We actually have a moonshine tradition of our own,” Peter says. “I had a great uncle who used to have a still in the mountains near Dunedin. We’ve got some newspaper cuttings of his exploits. He was fined 300 pounds, which he paid in cash. So we’ve got a little bit of history in that regard—not that we’re absolutely proud of it.”

Peter also remembers hearing tales about stills operating in the Hokonui Hills. “Growing up, you heard about these things but never saw them.”

Carol, Peter and Robin Tippett are attending the festival for the second time. They live in Dunedin but have a crib in the Hokonui Hills, on the upper Mataura River, where they have been holidaying for 30 years. Carol says they regularly walk the tracks along Whisky Creek and imagine the days when the hills and gullies were home to illicit whisky production.

Though there are surely McRae descendants among the festival-goers, Jim Geddes says few of them will have any detailed knowledge of their family’s sly-grogging past.