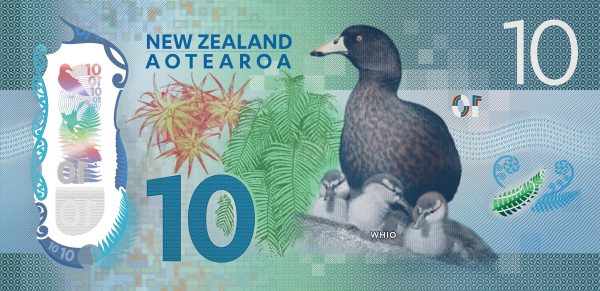

Hoiho

The story of the bird on our $5 note.

At spots on the Otago coast during spring and summer, nature puts on a reliable late-afternoon show. Yellow-eyed penguins, or hoiho, emerge from the sea and waddle up the beach, each heading to its private, lifelong nesting area.

Sporting a unique yellow headband and eyes, they belong to one of the world’s rarest penguin species, and the fourth largest—adults reach almost half way up your thigh. They are objects of desire for many tourists, but their guardians wish that people would view the penguins only with one of the area’s recognised guides. They decry the recent craze of getting selfies with this threatened species.

“The tikanga surrounding this taonga bird and the stories of old come from the observation that it’s a shy bird,” explains Yvette Couch-Lewis, the Ngāi Tahu representative for the hoiho recovery programme.

“It stands on the beach once it’s come ashore and people think the bird’s posing for them [to photograph it], but its heart rate is doubling. They are stopping it getting back to feed its chick and relieve its mate.”

A missed meal can be life or death for a chick in years of poor food supply, according to Bruce McKinlay, author of the Department of Conservation’s hoiho recovery plan. He agrees that hoiho need people to leave them alone, especially during the breeding season.

Food is hard-won for hoiho: a penguin returning from fishing may have swum 25 kilometres offshore, making perhaps 200 dives of up to 120 metres deep. It must then plod over rough terrain as far as 700 metres inland, before proclaiming its arrival at its nest by screeching. (Hoihoi, from which the Māori name comes, means ‘noisy’.)

A particularly arduous challenge occurs in autumn, when the birds fast for a month on land while they moult.

Often the fishing isn’t good, and nest numbers can fluctuate wildly between years. This summer, only 260 breeding pairs have been spotted on the mainland, from Banks Peninsula down to the Catlins. Four years ago there were almost 500. The population elsewhere in its range—Stewart Island and the islands off it, and the subantarctic Auckland and Campbell Islands—is less certain.

The scene on the $5 note is from Campbell Island, with the Campbell Island daisy at the bird’s feet.

The low numbers dismay the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust, which has been protecting hoiho for 30 years with the help of corporate sponsor, the Mainland brand. It has supported a community revolution in removing stock from coastal farmland, planting shrubs and controlling predators. It owns land where hoiho nest, and rehabilitates injured, diseased and starving penguins.

The land-based remedies have likely saved the species so far, but a self-supporting population remains elusive. Many suspect a problem lies at sea, where the penguins spend half their lives.

“We know so much about the terrestrial environment, but very little about the marine environment’s effects on them,” says Sue Murray, the trust’s general manager. The trust recently employed a science advisor to explore an oceanic tangle of dynamics: food competition, disease, predators and temperature changes.

Commercial fishing nets are a known trap. Hoiho dive to the sea floor to catch juvenile fish, and nets drowned at least six last year. The Ministry for Primary Industries is working with others to reduce this toll, recognising that for a species that is barely hanging on, every penguin counts.