Hauturu – Resting Place of the Wind

Mountainous, densely forested and bounded by cliffs and boulders,Little Barrier Island (Hauturu) crouches in the outer reaches of the Hauraki Gulf, a relic of a wild New Zealand now largely vanished. Set aside as a nature reserve over a century ago, the island houses a matchless cargo of wildlife inhabiting an unusual diversity of forest types.

From the forest ahead there is a penetrating whistle followed by an avian rendition of a car ignition being turned over: tit–tee, to–tee, to–tee, to–tee, to–tee. Further off, a similar call echoes back. The dark shapes of four starling-like birds jump and flutter into sight, pushing onwards through the shrubbery below a flock of smaller birds working the sub-canopy.

This quartet of tieke, or saddlebacks, are vanguard to the main body of 20-odd popokatea, or whiteheads. Successive volleys of cheet, cheet . . . cheet enable the observer to easily track the popokatea, which are feverishly searching, feeding and chirping. By holding station with them, one remains within the nucleus of the mixed flock.

Above and to every side are riroriro (grey warbler), korimako (bellbird), tui, titipounamu (rifleman), miromiro (tomtit), kakariki (red-crowned parakeet), toutouwai (New Zealand robin) and even a pair of exquisite hihi, or stitchbird. Such a flocking can number over 200 birds and, although long since a thing of the past on the North Island, a short kereru flight distant, is still a common occurrence on Hauturu.

Some years ago, long before actually landing on Hauturu, I read a 19th-century account in W. R. B. Oliver’s classic New Zealand Birds. Oliver recorded the saddleback as having a peculiar association with whitehead; how two or more saddlebacks followed a flock of whiteheads and acted as guardians to it.

Eventually the saddleback became extinct on the mainland, but I never forgot Oliver’s description of tieke with popokatea—although I never expected to witness such a spectacle with my own eyes. But witness it I did—and did most days while living and working on the island with my partner, Irene Petrove, and 13-year-old daughter, Natasha. From 1996 to 2000, Irene was the Department of Conservation ranger on Hauturu/Little Barrier Island.

Hauturu rises impressively from the outer Hauraki Gulf about 75 km north-east of Auckland. It is a 2817 ha island, 722 m high and one of the most important wildlife and forest reserves in the world. Under the stewardship of the Department of Conservation it has 34 species of breeding native bird, many of which are endangered or rare, two species of native bat and at least 14 reptile species, including the tuatara and the very rare chevron skink.

The insect fauna is varied, with its most distinctive representative, the wetapunga—a giant armour-plated cricket with crayfish-like legs—now found nowhere else in New Zealand. The island has 10 indigenous species of earthworm, including two endemic forms, and there are at least 42 species and subspecies of land mollusc.

Much of the island’s higher elevations are still covered by primary kauri and hardwood forest, and with the exception of the kiore, or Pacific rat, it has no introduced mammalian predators or herbivores. A century of vigorous regeneration has seen its once denuded lower slopes now clothed in tall kanuka, pohutukawa, puriri, kohekohe,karaka and mahoe forest.

On a grassy, south-western flat nestled between the forest and the boulder-lined coast is the ranger’s homestead where Irene, Natasha and I lived for four happy years. For us, Hauturu meant many things: sipping a cool drink on the verandah while watching an autumn sun set behind Taranga Island; hunching in torchlight over a faulty diesel generator at two in the morning; the jaw-dropping spectacle of 40 spooked, screeching kaka taking to the air from a red-speckled pohutukawa; rude nocturnal awakenings by rowdy korora (little blue penguin), kiwi and pateke (brown teal); the somewhat frustrating experience of being public property to conveyor-belts of visitors all asking the same questions.

Being DoC’s representative on the island is a multifaceted role. Primarily, the ranger must ensure that all visitors hold a landing permit and are carefully briefed to ensure that none of the island’s extraordinary wilderness values are compromised. As well, she or he patrols the island by boat to check that no one lands illegally.

People continually come ashore without permitsyachties walking their pets, Waiheke hippies with a nautical bent poaching large kauri trunks from the foreshore, and even dope-growers tending their plots. In 1997, Irene happened across one of these dope-growing operations, discovering over 3000 marijuana plants.

Boat patrols also involve talking to people, educating and assisting the public. Maintaining a good relationship with the fishermen of nearby Leigh is important, too, as not only do they have a strong long-term bond with the island and its bays and reefs, but they are also supplementary “eyes and ears” for the ranger.

As well as her departmental protection duties, during her time on the island Irene managed a successful tuatara captive-rearing programme, set up the seasonal noxious weed team (the main target of which is climbing asparagus), liaised with tangata whenua and co-ordinated several conservation volunteer work schemes.

A good ranger has to be able to work in the field alongside a wide spectrum of people, from brilliant, socially-inept scientists to youths who have difficulty telling the difference between a tui and a tuatara! As well, there is the administrative work to be done in the homestead office. Unlike a century ago, a remote offshore island in these days of email, fax, cellphone and laptop is not beyond the reach of a tsunami of bureaucratic paperwork.

For Natasha, Hauturu meant Correspondence School courses during the day, and in her spare time lots of reading, riding her bicycle, building huts and climbing trees. Our “pets” were wild kaka, tui and pateke, and a kereru which regularly visited the homestead to be hand-fed bread and bananas. This bird, called Pidge, has been visiting successive rangers and their families since 1983.

As a family, we fished, swam, snorkelled for crayfish, walked in the bush and enjoyed picnics on the coast. Indoors, we thrashed card games, Monopoly and draughts and listened to music in front of the fire. Sometimes we had visitors from the bunkhouse over for dinner. Around 350 people visit the island every year, with many of them staying for a full two-week stint. More and more, we saw the tangata whenua returning to their roots.

[chapter break]

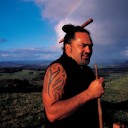

Hauturu is traditionally an island of the tribe Ngati Wai , although it is the manawhenua of the hapu Ngati Manuhiri. Tribal ancestors from Hawaiki may have discovered the island well over 1000 years ago. Long before the arrival of the legendary ocean-going waka of Tainui, Arawa, Takitimu and others, Toi the navigator hove to off what is now known as the West Landing, near Te Titoki Point.

Toi was searching for his grandson Whatonga, and to see if he was on the island he threw his dog, Moi-Aue-Roa, overboard and instructed it to carry one of his slaves on to the beach. The sea was rough that day, with large waves breaking along the foreshore, and, paddling just beyond the breakers, Moi-Aue-Roa refused to land the slave.

Enraged, the slave killed Moi-Aue-Roa with his weapon and swam ashore, dragging the dog’s carcass onto the foreshore, where it turned to stone. To this day, Moi-AueRoa, or the Dogstone, can still be seen lying on the boulder beach close to the West Landing. It is, of course, tapu, an uruwhenua, or special location, where fishing catches or fishing equipment have been consecrated over the ages.

The Dogstone’s flattened upper side is pat–u-shaped, about 1.8 m long and over 80 cm wide. On its back can be seen a distinct 15 cm-long gouge—the mark made by the slave’s weapon.

I have seen similar gouges oozing blood from the shins and legs of human visitors trying to negotiate the dacite boulder beach on that same stretch of coastline. Seaborne arrivals and departures on Hauturu are often difficult and occasionally dangerous. The dacite volcanic island has no sheltered harbours or sand beaches, but instead provides extensive banks of smooth pink, blue, brown and grey boulders—I call them “Tangaroa’s marbles”—backed by high breccia, dacite and rhyodacite cliffs. Moving up and down the beach over these unstable boulders can be a balancing act akin to tightrope walking, especially when they are wet and slippery.

Despite the harsh coastline and the hard, unforgiving intertidal zone, which complicates access, some of Toi’s descendants later came to settle on Hauturu. Today there remains substantial evidence of the early Maori occupation: excavated clearways for canoes, long rows of stones and the remnants of collapsed walls round former gardens, which provided gourds, yams, taro and kumara. On several sheer promontories, pits, scarps and terraces now sprouting venerable native trees mark the locations of both kainga and palisaded pa.

More subtle clues lie beneath the leaf litter: compacted shell layers, the remains of paua, nerita and limpets, which spill out from eroded faces. Such midden sites can be found close to the coast and also at much higher elevations further inland. As well as these ancient dump sites of kai moana, one sometimes comes across a shard of coal-black obsidian, a material used by early Maori for cutting tools and thought to originate from Tuhua, or Mayor Island.

From about 350 years ago, wars were waged between Nga Puhi and tribes around the Waitemata, Kaipara and Hauraki regions. During this pre-European phase a number of battles were fought on Hauturu, the most significant being at a location called Te Pua. Here an attacking force of Nga Oho, led by the chief Makinui and his brother Mataahu, defeated and killed many of the island’s inhabitants.

Nga Puhi rangatira Pomare is recorded as having lived on the island, and the formidable Hongi Hika, over the course of eight war expeditions between 1822 and 1830, stopped off at Hauturu a number of times.

To my mind, Hauturu is a classic South Seas isle: it has a symmetrical volcanic silhouette, a Polynesian heritage, jungle-like palms and foliage, colourful birds, including parakeets and parrots, and the all-pervading South Pacific Ocean lapping against its beaches.

The sea, especially the undersea environment, is a taonga of Hauturu often overlooked by visitors. Hauturu’s underwater world is a mere cast with a rod from those gaily coloured tieke and popokatea chirping from puriri and gargantuan pohutukawa on the shoreline.

Donning mask, fins and snorkel, then easing into the sea for the first time, a diver can be overwhelmed by the marine life and underwater vistas, especially when visibility exceeds 15 m. Leaving behind the topside boulders, sheltering moko, shore and copper skinks, one swims over submerged boulders literally crawling with crabs, sea stars, chitons, shrimps, limpets, paua, whelks and large trumpet shells.

Onwards, in deeper water, the bank of boulders continues to fall away. An octopus can sometimes be seen slithering through a gap between boulders, which are now completely smothered by brown seaweeds such as Car pophylhnns and the lighter-coloured Ecklonia. This dense tangle of marine plants can be as hard for a diver to get through as Hauturu’s terrestrial jungle of divaricated manuka, supplejack, mangemange and bush lawyer is for the tramper.

Darting about over these seaweeds are spotties, the occasional wide-bodied parore and leatherjackets, while finger-sized triplefins guard their territories from the top of the cannonball-smooth rocks.

Among the rocks are kina, which love eating Ecklonia. They are competent climbers, motoring like miniature army tanks onto a holdfast, then inching up a metre-long stalk to the head of the plant, where they eat the strap-like fronds.

In this habitat it pays to keep a lookout for crayfish feelers. The red crayfish is the most commonly encountered, although occasionally one will find the much larger green or packhorse Cray.

Further out over the sand, in the scuba-diving depths off Te Titoki, scallops can be found, although they are becoming rare as commercial dredgers continue to plough their beds into oblivion. Rays are more common. Long-and short-tailed stingrays can weigh over 100 kg, and if a skindiver knows what he is doing, these creatures are good for an extended ride by hanging on to the tail.

Eagle rays are the most numerous, with groups of five to ten animals working a patch of broken ground together. While feeding, eagle rays flop around into very shallow water, with both wingtips breaking the surface. Off the southern coast of Hauturu, eagle rays have even been known to beach themselves on dry boulders to escape orca charging after them into the shallows.

Following the boulder–sand interface, swimming parallel to the coast, a diver is likely to find many more species of fish species. Swarms of juvenile blue maomao school close to the surface, snapping at the wake of swirling bubbles. Occasionally a koheru or some other unidentified silver fish zips by like shrapnel.

More sedentary are red mold, goatfish, marblefish and solitary hiwihiwi, tucked into cracks. Butterfish sweep through the Ecklonia forest, and insect-like clouds of tiny fish hovering just off the bottom prove to be schools of oblique-swimming triplefins.

John Dory and juvenile snapper feed over the sand. I have been diving Hautum’s waters for 20 years and can’t remember having seen so many snapper as I did during the last two years I lived on the island. On one snorkel dive a ten-pounder came in close and hung around as if waiting for a hand-out, as they often do at the Goat Island marine reserve close to Cape Rodney, about 24 km distant. I wonder if Hauturu is reaping the benefit of having a marine reserve off the adjacent mainland.

Other fish to be seen, especially in the clearer oceanic water off Hauturu’s north-eastern faces and stacks, are clown toado, schools of spotted demoiselles, butterfly perch, maomao, trevally, kahawai and large kingfish. Shark dorsal and tail fins are often spotted, especially in smooth seas. These are species such as mako, school shark, bronze whaler and even the occasional basking shark—all shy, and unlikely to allow one to get close.

Bottlenose dolphins often work the shallows, and have been observed chasing kahawai and forcing them to strand themselves high and dry—a scaled-down version of the orca/eagle ray hunt. One of the dolphins’ favoured hunting stations is the tidal race off Te Titoki, and here one sometimes finds the mummified carcasses of kahawai baking on boulders above the high-water mark.

[chapter break]

Although its marine life is impressive, Hauturu is best known for its splendid forests and rich native birdlife. It carries the most intact, unmodified tract of warm temperate forest left in Aotearoa, even though the island is not the pristine botanical ecosystem many of us would like to imagine.

Hauturu has sustained a fair amount of collateral damage during its association with humans. The impact commenced centuries ago, with Maori burn-offs incinerating at least half of the island’s primordial forest cover. Virtually all the gentler lower slopes are now covered in regenerating kanuka–kauri ricker forest 95-130 years old.

From the late 1860s to the 1890s, considerable portions of the kanuka on the south-western flanks and the country inland of Ngatamahine Point were logged by Maori to supply firewood for Auckland.

Further assaults on Hauturu’s old-growth forest centred around the kauri-logging and gum-collecting industries. From March 1892, a logging co-operative between a Pakeha contractor and Ngati Wai commenced what was then hoped to be a five-year period of systematic felling to clear Hauturu of all its estimated nine million superfeet of merchantable kauri. However, after eight months of energetic cross-cut sawing had taken place, the government of the day issued an injunction stopping the project.

By this time the island’s first appointed ranger, Henry Wright, had noted: “. . . the felling and hauling of the kauri had already made great havoc with the bush [in Awaroa Stream] . . . every kauri tree of sufficient size having been removed. . . . Eight white men were up Waipawa [Stream] felling kauri and drawing it out with bullock teams . . . .”

Large quantities of kauri gum were also collected on Hauturu. Gum was often found lodged in the forks of trees, and had to be retrieved by climbing. It was also found on and under the ground, where it could be located by probing with long steel spears. Once located, it was dug out by hand. On some ridgetops there are precisely dug rectangular pits which may have had some connection with this industry or that of the tree-felling operations. There was speculation at the time that greed for the highly lucrative kauri resin may have been behind a later wave of fires that cleared the lower slopes prior to 1895.

Fire, logging, gum-digging . . . as if that weren’t enough, the island’s flora and fauna were further assailed by introduced browsing mammals. One Maori living on Te Maraeroa Flats during this period stated that there were about 30 head of cattle and no fewer than 1000 sheep ranging over the island. After a trip to Hauturu in 1893, the chief clerk of the Government Lands Department, Hugh Boscawen, didn’t mince words regarding the ubiquitous ungulates:

“From what I have seen of the place, next to timberfelling for destroying bush cattle are the worst, there is hardly a place they will not go, and they break and tear at supplejacks and other undergrowth for feed, in some places I could not have believed that it was cattle had made the tracks, unless I had seen their marks . . .”

Boscawen was visiting Charles Robinson, the second government ranger, appointed to watch what was hoped would soon become one of the country’s leading refuges for native birdlife. Robinson’s conservation ethics were not a little incongruous with the position he held. He reported to Boscawen that he had seen none of the rare stitchbirds, but admitted he would try to shoot some for “scientific purposes.” A Maori named Tenetahi, who was living on the island with his wife, Rahui, later made a sworn statement that he had seen two hihi skins in Robinson’s tent. Robinson also bagged kereru and kaka for the pot and even confessed to once having shot a kotare, or kingfisher, without thinking. Hauturu’s caretakers have come a long way since then.

The day came when Hauturu was officially gazetted a wildlife reserve. Under the provisions of the Little Barrier Island Purchase Act 1894—a mere stroke of a quill pen—the island was abruptly deemed to be Crown land. There was a problem though: some of the resident tangata whenua did not want to part with their home.

From his Ngati Manuhiri viewpoint, retired policeman and Hauturu historian Roi McCabe provides some details of the island’s traditional ownership and the questionable practices resorted to by the colonial government to convert Maori land to Crown land:

In a letter to the Government land agents in 1862, Te Kiripatuparaoa (who lived at Te Maraeroa for up to sixty years) stipulated the names of owners favouring Ngati Manuhiri and Ngati Wai. When Te Kin died in 1872 he left manawhenua of the island to his daughter Rahui to Kin. This was the start of an ongoing 22-year dispute between Maori factions contesting the ownership of Hauturu. In 1878 Rahui lodged an application in the native land court to have the title of Hauturu legally established. After numerous court hearings also involving Ngati Whatua the court found in favour of Ngati Wai in 1886. By 1891 these owners entered into negotiations with the Government to sell the island, however the sale was conditional. The Government procrastinated and the agreement lapsed. In January 1892, via an advertisement in the New Zealand Herald, the Ngati Manuhiri hapu withdrew their consent to the sale of the island. Despite this the Government commenced to approach individual owners and paid them out, while Ngati Manuhiri still remained in lawful occupation of Hauturu. At this point the Purchase Act 1894 was enacted to divest Ngati Manuhiri, and by 1895 an ejection order was issued. On Sunday 19th January 1896 a force of armed Government troops landed at Te Maraeroa and took Ngati Manuhiri (including Tenetahi and Rahui) from their homes and shipped them back to Auckland Prison in chains.

With Roi’s words in my head I gaze from a choice vantage point over Te Maraeroa, with the sea behind and the mainland on the horizon. On the flats in the middle distance are the implement sheds, providing cover for boat, tractor, tools and diesel generators. The sheds sit against long mounds of heaped grey boulders nearly hidden by an advancing mat of rank grasses.

A fresh nor’easter has the largest pohutukawa shaking their limbs and leaves. Distant speckles of white and green mark the positions of kereru. Twenty to 30 birds feeding on clover lift off as a kahu (Australasian harrier) contour-flies over the miniature savannah stretching westwards from the ranger’s homestead. Lanky dots of blue and black are pukeko using their orange bills to grub grass roots.

Near the mouth of Waipawa Creek can be seen the scraggy head of an old hollow puriri tree. I was once told of two equally old tuatara that used to live at the base of this tree. The puriri and those long-lived reptiles may feasibly have witnessed the passage of Lieutenant James Cook’s barque HMS Endeavour in 1769. Cook gave the island its European name when he sailed past on his first historic exploration of Aotearoa. Tuatara and tree probably also saw Ngati Manuhiri booted off their island.

The melodious chirps of korimako jolt me into the foreground of consciousness. A rustle, then I see a piwakawaka (fantail) fluttering close to the ground, while above it a tieke works the trunk of a treefern. The tieke glides to a branch, then bounds through the poroporo shrubbery like a fast-forward version of its larger cousin, the kokako. Its blurred figure jerks here and there until suddenly it stops, red wattles swinging pendulously as it stares at an indistinct object. The bird assumes the “get-set” pose of a human sprinter, then its huia-like bill snaps down yet another insect.

Unfortunately, this consummate avian predator of invertebrates has proved easy prey for introduced mammals. By the turn of the 19th century, Hauturu’s original population of tieke had become extinct—wiped out by feral cats. For over 100 years, beginning some time after 1870, cats ran wild over the island, devastating the native fauna—insects, reptiles, bats, birds, eggs, even snails. Hihi, one of the rarest passerines in the world and at that time found only on Hauturu, became exceedingly hard for professional specimen collectors to shoot.

Other rare endemic birds released on the island “sanctuary” fared no better, being also quickly killed off. The most notable of these were kakapo (introduced in 1903), roa, or great-spotted kiwi (1915) and tieke (1925). Black and Cook’s petrels were also slaughtered in great numbers not only by cats but also by kiore and probably dogs and pigs too. On a number of visits to Hauturu in the 1880s, the notorious tomb-robber and collector of rare bird skins Andreas Reischek reported Maori dogs and feral pigs wandering free all over the island. These animals were gone by the time Maori were forced off in 1896, although the cats remained.

For decades, Hauturu’s rangers shot, trapped and poisoned wild cats. However, despite commendable efforts, Felis catus continued to range far and wide. In 1968, the Department of Lands and Survey commenced a systematic cat-eradication programme, with the field operation being run by the New Zealand Wildlife Service.

First, a viral disease, cat distemper, was used, and this biological control reduced cat numbers by about 80 per cent. Some trapping followed, then the operation faltered and momentum was lost. Scientific objections to the planned eradication had surfaced, because some academics considered there was little evidence of cats having a detrimental effect on the island’s fauna!

By then, the grey-faced petrel could no longer be found, and the hard-won field data accrued by Wildlife Service scientist Mike Imber showed cat predation on the black petrel population to be so high that no young whatsoever were fledging. On the basis of this evidence, cat-trapping and poisoning recommenced with vigour in 1978, and by March 1981 Hauturu was officially declared cat-free.

In the seasons that followed, a second wave of threatened birds was released: kakapo (1982), tieke (1984-87) and kokako (1981-94), and this time the respective species survived and bred. By the late 1980s, hihi numbers had also increased sixfold.

Kiore remain on the island, despite their considerable impact on Hauturu’s indigenous flora and fauna. This agile, semi-arboreal rodent is known to be a predator of kakapo, Cook’s petrel, toutouwai, tui, tieke, tuatara, bats, snails and insects. The island’s annual spring/summer irruption of hundreds of thousands of kiore consumes not only huge numbers of insects and animals but also prodigious quantities of fruit, flowers, seeds and leaves.

Several metres from my position, a movement catches my eye. There in the short grass, in broad daylight, are four—no, five—kiore foraging for the sparse autumnal feed. The animals move back and forth, working into the wind with their noses keyed for edible scraps, live prey, or even each other!

Two of the rodents suddenly start chasing each other around. They separate, face off, then charge again, jumping up onto hind legs with forelimbs stretched high to paw each other. They do this again and again. I don’t have a clue what they are up to. Their behaviour looks so quaint, even though it could well be a fight to the death.

Out of sight, thousands of their furry brethren have overrun Te Maraeroa Flats. Many are slow and weak-looking and will invariably be taken by native predators such as kahu, ruru and pukeko.

forest creatures at low densities.

Kiore were traditional kai for Maori. They accompanied the early Polynesian explorers and settlers in their ocean-going canoes, and as no hybridisation has occurred with the two rat species subsequently introduced by Europeans, they are biological indicators of ancient Maori migrational routes. This historic significance is one of the reasons why some factions within Ngati Wai claim the kiore as a taonga.

In his book Little Barrier Island (1Iauturu) the late W. M. Hamilton recorded kiore as being widely distributed throughout the island, from the summit down to the high-water mark on the coast, although they appeared more numerous at lower elevations, particularly over the winter months.

Hamilton was a field scientist of the old school—an academically qualified naturalist, meticulous in recording his day-to-day observations, enthusiastic, unassuming, physically strong and not a little adventurous. He explored Hauturu extensively from 1932—even honeymooning on the island with his wife in 1945—and kept returning to the island up until the late 1980s.

Here is an excerpt from his 1932 field journal, describing an eight-day fly-camping mission into Hauturu’s hinterland with John and Hubert Morrison during January:

We seemed to be falling right into the depths of the earth and have come down about 1000 feet from Orau into a dark, dimly lit gully with the hills towering 1000′ on all sides—just at the south foot of Orau. Where our creek joined the main gorge we found a small flat of debris deposited by the creeks—the only flat in the gully we found later—and although everywhere was soaked we set to work and built a nikau shelter and got a fire going in the bed of the creek—everywhere soaked. Efforts were highly successful and we were able to dry our wet clothes and felt quite warmed up and cheerful in spite of the wet. Late in bed.

About 8:15 the petrel (Cook’s) commenced to come in from the sea in their thousands filling the air with their cries of ti-ti-ti, the swish of their wings sounding like the surge of a distant waterfall rising and falling irregularly as the birds drop from a higher altitude to the level of the gorge. Their nearest feeding ground is said to be 25 miles away but they regularly camp on Hauturu and Taranga above about 800′. Their flight inland continues for just over an hour when the noise subsides somewhat as they settle down for a short rest. Many are killed by collision with trees in landing or with other birds and are found dead in large numbers in the bush. Several landed just outside the range of our firelight and visited us again overnight. With the large numbers which nightly visit the island it is highly probable that they exert considerable influence on the character and growth of the underscrub on the higher parts of the island. Their visits have been one of the most wonderful things we have observed here.

Our camp tonight is particularly cosy. The bright fire lighting the whare and a little circle of undergrowth serves only to intensify the blackness of the stream bank where numbers of glowworms show like fairy candles through a tracery of filmy ferns. Through the canopy of tree-heads which meet across the stream a thin filter of moonbeams light up our camp smoke as it drifts slowly up out of the gorge—and so to sleep to the ceaseless chatter of ti-ti. Mr M. up early and built up fire—not raining but difficult to judge the weather or the direction of the wind from down here. Decided to stay in the gorge and explore today so left our camp and took lunch downstream. We had only proceeded a hundred yards or so downstream when our way was blocked by a 25 foot fall—this called our rope into service only to find a 35 foot fall just below—this was negotiated on the right bank close to the fall with a short rope for safety. The third fall was not much further down and was tackled by passing up to the right and along the bank then dropping some distance onto a ledge and working down to the right into the creek. The fourth falls were 60 feet high and dropped into a gorge with 250 foot perpendicular sides—by throwing a rope by aid of a stone over a tawhero tree we gained a wide ledge which let us travel down to the stream bed. The next falls were 50 feet high and fell into a 300 foot gorge requiring a detour on the right bank for some distance until we reached a side tributary and were able to scramble down with a short rope. The going then became much improved with a gradual fall leading into the Gorge. The walls became higher and in many places overhung with curious holes high up on the sides; in places narrowing in till only 6 foot wide at the bottom, at others widening out to take a sweeping bend but always bare of vegetation for 300 foot or so. We were expecting at any minute to find another fall to bar our progress but the going held and we shortly afterwards got a breath of sea air which spurred us on till we rounded the bend and saw the sea . . . Scrambled round boulders to cove and enjoyed a swim followed by lunch in the sun—surrounded by towering cliffs on three sides. Commenced our return at 3 p.m.

[chapter break]

A few hours later, John Morrison found a pate tree with some wood rose, Dactylanthus taylorii, growing from its root system. Dactylanthus is a very rare endemic root parasite. In 1998, a DoC survey team guided by Irene followed up Hamilton’s record and ended up discovering a further 70 plants on the ridge immediately east of Orau Gorge. To date, Hauturu is the only offshore island where Dactylanthus has been found.

Following the euphoria of the 1998 find, many of the plants had wire mesh cages erected over them as protection against kiore killing them by eating their buds and beautiful, unearthly flowers. Unfortunately, cages also prevent the native pollinators such as pekapeka, the short-tailed bat, and as yet other unknown reptile or bird propagators from reaching the flowers. As a consequence, every April/May season the so-called “flowers of Hades” must be laboriously hand-pollinated.

Hauturu is many things to many people. For scientists it is most often a place of study and academic toil. Others are drawn to its lore and its Maori and Pakeha history. For conservation volunteers and seconded tradesmen the island may just be a work site. Good catches of fish, scallops and crays draw another type of visitor to its shores. For tangata whenua it is sacred ground, the resting place of a long line of tupuna. Most visitors, however, come to experience Tane’s world—to hear and see the forest birds. For Irene, Natasha and me the essence of Hauturu is that wild interface between sea and forest, encapsulated in experiences like these:

• watching brown kiwi feeding at night under pohutukawa on the foreshore, then several hours later having a pod of orca working the shallows along the same coastline.

• washing down gear after a dive, with a dozen curious kaka perched on our shoulders, on strewn wetsuits and also on the catch bag full of kai moana, their hooked beaks tentatively touching the feelers and spiked claws of kicking red crustaceans.

• one-metre swells crashing onto the boulder beach while waist-deep Maori and Pakeha work together to transfer goods, equipment and people between tlle island and anchored service vessels.

• at water’s edge, holding a captured female kakapo in one hand and a recently found intact paper nautilus in the other.

[chapter break]

Recently a whanau of Ngati Manuhiri made a pilgrimage to Hauturu. They were the mokopuna of Tenetahi and Rahui—the great-grandsons, granddaughters and great, great-grandsons living at Pakiri on the adjacent mainland. They had come to walk the ground. Two of them explored the forest interior while the others walked over to see Moi-Aue-Roa, the Dogstone.

We found the tide lapping at the edges of the grey stone, and the two young boys traced their fingers along the gouge mark left by the slave’s weapon. The younger boy looked under it for crabs and sea stars, but the other continued to stroke its pitted surface. Behind the boys, the adults sat on the boulders. One of them, Sam Williams, recorded the scene for posterity with his videocam, talking into its microphone: “Riki had his 10th birthday today and he will never forget it.”

Once Sam had finished filming, I mentioned to him my recurring urge to one day place an offering on the Dogstone. For whatever reason, I had never got round to doing it, despite going on scores of kai moana expeditions. What would be appropriate, I asked? A snapper? Crayfish? Sam turned from the boys and bent down to scoop up half a dozen nerita shellfish in his free hand: “Sid, even these would do, or a kina. Place them on the stone. In that way Tangaroa is placated and the offering still lives for when the tide comes in.”

I took the advice on board. There was some more talk, then silent contemplation before we headed back. Later, after the whanau had departed, I started the walk back to the Dogstone, barely noticing some disturbed tieke sounding a retreat as I ambled towards the shore.

I couldn’t forget the words of one of the young boys who had visited: “To Te Kiri, I, one of your mokopuna, followed the wind knowing where it will rest. Tane’s children surrounded me and the songs of birds’ karanga echoed as we came ashore. The eyes of the patu-paiarehe still inhabit the high places. I whisper to the wind the joys, the sorrows of my heart, knowing that they will reach this place.”