Gun country

Last century, firearms flooded into New Zealand with returning servicemen, and during peacetime guns became synonymous with an honest, healthy way of life in the hills. Now, there are thought to be 1.5 million firearms in New Zealand—one for every three people—used as conservation or farming tools, or simply for sport. To some, firearms symbolise self-sufficiency and responsibility. To others, they’ll never be more than instruments of death. But is this issue as clear-cut as it seems?

It is the autumn of 1993, just a few weeks after the death of my mother. My dad and I peer out of the window of pilot Dave Saxton’s Hughes 500 as we fly low over the South Westland forest. Sheets of rain bead off the Plexiglass, while the tops of rimu and kahikatea sweep by beneath us. I am 12 years old, and Dad has brought me on this trip to undertake rural New Zealand’s most sacred rite of passage for young men: I am here to shoot my first deer.

The chopper lands on the bed of the Stafford River, just south of Jackson Bay. As it takes off again, the silence of the mountains closes in on us. The river gently combs its gravel banks, and the drizzle intensifies. We set up camp in Stafford Hut, nestled between the forest and a wild beach. In the evening, with the rain clearing, we walk up the river. I have Dad’s ex-army Lee–Enfield .303 tucked under my arm, one cartridge in the chamber.

As we wade around a bend in the river to a gravel flat, a damp spiker trots out onto the stones and sniffs the wet air.

Dad steadies my hand as I go for the bolt. I ease the mechanism forward, like I’ve been taught to do, feeling the cartridge slide into the breech and the spring gather its load of stored power. Carefully, I bring the rifle to my shoulder, nestling the brass butt plate into the hollow of my collarbone, and line up the young deer, centring the open “V” sight on its shoulder for a clean heart shot, making sure to squeeze, not pull, the trigger.

The detonation of the cartridge fills the valley, and I seem to feel, more than hear, the thud of the bullet striking home.

The deer staggers forward, then slumps onto the riverbed.

[Chapter Break]

I grew up on a sheep farm in the Rakaia Valley in mid-Canterbury. The gun cabinet in my father’s truck shed held a basic arsenal, typical of that owned by many generations of New Zealand farmers.

There was the side-by-side shotgun I inherited from my grandfather. When I peered down the barrels, I inhaled decades of cleaning oil and smoke, and the smooth interior concentrated the world to a metallic whorl.

Then there was the old single-shot .22, Dad’s faithful rabbit gun, later to be replaced by a more efficient semi-automatic Ruger 10/22 with a scope.

But king of the cabinet was Dad’s open-sighted, bolt-action Lee–Enfield .303, its dark walnut stock clasping a metal barrel as tough as a tank. Reliable and rugged, thousands of rifles just like this one returned to New Zealand with servicemen after the World Wars and became a staple of farm life. As hunting rifles, with their wooden stocks cut down to make them lighter, they culled countless deer, tahr and chamois. Dad’s own .303 is scratched and pocked from the years he spent bashing around the mountains, and a stag’s head is crudely engraved in its stock—the product of some rainy day holed up in a hut deep in the Southern Alps.

And yet, hunting stags in the hills is not what this rifle was designed for. Manufactured in the millions at the Royal Small Arms Factory on the outskirts of London in the early 20th century, the Lee–Enfield was created for one purpose: to kill human beings as efficiently as possible. These rifles left multitudes of soldiers dead in the mud in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, as well as along the Korean Peninsula and in Afghanistan. And herein lies the dilemma of gun ownership—that these tools, which hold an important place in our cultural identity, are also capable of the cruellest slaughter.

After I shot my first deer with Dad’s Lee–Enfield, I helped him gut it in preparation for the airlift out the next day. Beyond the satisfying thought of a freezer filled with venison, I don’t remember any particular sense of triumph.

What I do remember is cooking a meal in the hut that night with my father, then lying awake in my sagging bunk, listening to the roar of the surf, aware of the great weight of the Westland forest.

[Chapter Break]

When a man walked into two Christchurch mosques on March 15, 2019, and shot 51 people dead and injured 49 others, New Zealand struggled to come to terms with what had happened. The man had wielded five guns—two semi-automatic rifles, two shotguns, and a lever-action firearm—and within weeks of the attack the government had introduced reforms to the Arms Act, banning most semi-automatic firearms as well as many pump-action shotguns and large magazines. A nationwide buyback scheme was announced to collect the newly illegal guns.

When I travel around the lower South Island in late 2019 to gauge the mood of the firearm-owning community in the wake of the recent reforms, I find myself caught in a crossfire of opinion. The ban affects thousands of firearms commonly used for hunting, target shooting and pest control. Collectors, too, are affected. Semi-automatic rifles have been in New Zealand for well over a century and, to the fury of some antique arms enthusiasts, the buyback includes many valuable and historic pieces.

I talk to firearm owners who are shocked at the speed with which the government has implemented the reforms. They decry the changes as crudely done and ineffective at preventing mass shootings. I hear talk of civil disobedience, of firearms disappearing into the black market. I approach people who refuse to speak; others hammer me with hours of passionate polemic. At the heart of it all, I discover, is a widespread fear that the government aims to make the private ownership of firearms illegal.

“We don’t know where it’s going to stop,” says Francis Helps, who has been a gun enthusiast from a young age. Like me, he learned to hunt with a Lee–Enfield .303, and continued with the sport throughout his life, representing New Zealand at target shooting. He lives in Flea Bay on the edge of Banks Peninsula, where his family runs a tourism business based on kororā (little blue penguins). His wife, Shireen, also grew up shooting.

“We were a poor family,” she tells me. “My father put a rifle in my hands at about 15 and told me, ‘It’s your job to make sure the dogs have plenty of food.’ I had to shoot for us occasionally, too. We ate, rabbits, hares, even possums.

“I’ve been on many a hunt with Francis. It got to the stage where our only holidays were up in the wop wops, in a rat-infested hut somewhere. It’s just as well he married me.”

Francis has spent many years mentoring young people in firearm use, including many people with disabilities. Hunting with the proper training, he says, builds strength of character.

“It teaches self-reliance, discipline and ethics,” he says. “It doesn’t turn people into terrorists. It actually turns them into responsible people.”

He sees the new legislation as an attack on his way of life. Societal norms, he says, are shifting, and enthusiasts like him are finding themselves marginalised.

“When I was young,” he recalls, “we’d flag down the railcar armed with a .303, covered in deerskins and blood, then go pedalling through Christchurch at one o’clock in the morning with a firearm over your shoulder. You’d get locked up for that now.”

[Chapter Break]

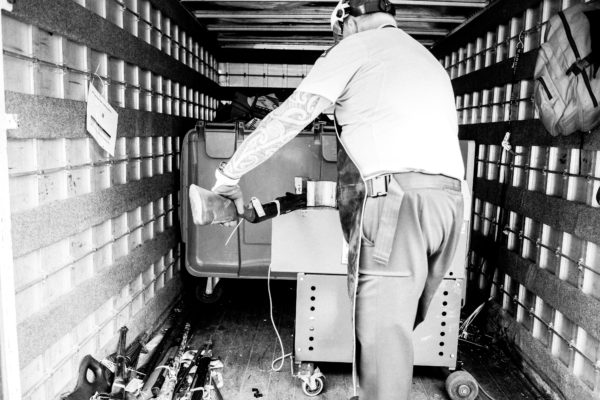

At a buyback event in a Christchurch community hall, the atmosphere is friendly, if somewhat tense. Numerous uniformed and plain-clothes police officers mill around.

There’s a handful of new military-style firearms in the bins, but much of what is coming in seems fairly old and tired. Many people, I’m told, are using the buyback as an opportunity to get rid of their old guns—taking the money straight down to the local gun shop to trade up for something modern.

I’m surprised at the number of firearms being handed in that are still legal. People are also using the amnesty as a means of getting rid of unwanted guns they may have inherited or just never use, despite the fact they aren’t reimbursed for these weapons. I’m saddened to see several historic Lee–Enfields in the disposal bins. One is a largely original Mk I from the 1890s. Later in the afternoon, this rifle will be bent in a vice and its chamber mechanism crushed, before it is shipped—along with hundreds of other guns—to another location to be destroyed.

Out in the carpark, I speak to people who have just been relieved of their firearms, and encounter a range of opinions. One man is happy to be rid of his disused .22s. Another is visibly furious, shutting his car door in my face and driving off. A stock agent who handed in a shotgun and a .22 tells me that, while the buyback is inconvenient, the farming community “has bigger things to worry about”.

I watch a couple of young-ish guys, both of whom wish to remain anonymous, hand in a large collection of military-style guns and accessories—all in immaculate condition and carefully stored in shockproof cases. They’re walking away with $30,000, having turned in over $4000 worth of magazines alone. This, they tell me, is their second trip to a buyback, and there are more to come.

They use their firearms for hunting, pest control and competition shooting, but also collect them as a hobby. Like many people opposed to the new laws, they say law-abiding citizens are being punished, and argue that the existing system of licensing just needed to be tweaked to close a few loopholes.

“We would have supported law reform,” one of them says. “I wouldn’t have cared how much it cost me to keep them.

“Anyone who should actually be allowed to keep [their guns] is turning up today. And all the ones you actually want to get rid of—where are they? They’re not here. So we’ve actually not achieved the goal.”

[Chapter Break]

As well as shocking many in the firearm-owning community, the recent gun-law reforms sparked a wave of protest from lobby groups such as the Council of Licenced Firearm Owners (COLFO). Meanwhile, gun-control advocates argued that the reforms didn’t go far enough. Many of us looked backwards, searching for an innocence it seemed we had suddenly lost.

But New Zealand has long had a troubled relationship with firearms. The first guns arrived here in 1642, brought by Abel Tasman and his crew, and when Cook landed in 1769, he too brought guns. Both encounters resulted in Europeans fatally shooting Māori they encountered. Then, in the early 1800s, firearms left over from the Napoleonic Wars flooded into the country, sparking the Musket Wars, a brutal reorganisation of intertribal power that resulted in an estimated 20,000 deaths.

New Zealand’s first firearm legislation was the Arms Importation Ordinance of 1845. It aimed to restrict the supply of “warlike stores” for the purpose of “subduing the present insurrection” of Māori. Māori warred extensively with the Crown in the 1850s and 1860s, and the government again attempted to regulate gun ownership with the 1860 Arms Act, which introduced a rudimentary, and ultimately ineffective, firearms register.

These days, prospective gun owners must obtain a firearms licence: they take a training course, undergo a background check, and prove they have a safe place to store their firearms.

Even so, there’s no limit to the number of firearms a person can hold, and it’s possible to buy dozens—or even hundreds—of guns without any official record of these purchases being made.

In the 20th century, gun use revolved around hunting. Following World War II and the influx of rifles brought home with servicemen, government hunters took to the hills—many armed with ex-military Lee–Enfields—in an effort to reduce the exploding deer population. In the 1960s, hunters started shooting from helicopters, often using semi-automatic rifles.

By the mid-1980s, cheap military-style semi-automatics (MSSAs) were widely available. When, in 1990, Aramoana resident David Gray used an MSSA and a .22 to take the lives of 12 neighbours and one police officer, the government moved to ban MSSAs. After resistance from firearm user groups, the ban was shelved. The minister of police at the time, Jack Elder, wanted to keep gun owners “on board” rather than “waving a big stick”. So, a special E-category licence was created for MSSA owners, which involved more stringent vetting. People had to provide a legitimate reason for owning an MSSA. (Self-defence was not considered a legitimate reason.)

It was to be the first of several failed attempts to ban MSSAs.

In 1997, a government-commissioned report by former judge Sir Thomas Thorp advocated radical gun-law reform. Thorp made 60 recommendations, including a ban and buyback of all MSSAs, and the creation of a firearms register. The Thorp report remains the most thorough examination of firearm law in New Zealand history. Despite numerous attempts at implementing it, only part of one recommendation was ever adopted. Resistance from pro-gun groups, sympathetic politicians, and the projected expense of some recommendations were behind the failures.

In 2017, a select committee conducted a year-long study of firearm laws, and made 20 recommendations, but then-Minister of Police Paula Bennett rejected most of them. The New Zealand Police Association slammed Bennett for bowing to lobby pressure. In particular, police decried a gun-law loophole whereby the AR-15, a cheap MSSA, was permitted in New Zealand under a standard firearms licence, provided it had a moulded plastic connecting the handle grip to the stock and a magazine capacity of less than seven rounds.

An AR-15, fitted with illegal high-capacity magazines, was reportedly among the weapons used by the Christchurch shooter.

[Chapter Break]

Almost 250,000 people in New Zealand hold a firearms licence, and it is estimated we have one of the highest per-capita rates of firearm ownership in the world. Tens of thousands of firearms are imported every year, but even so the rate of firearm-related crime here is low by global standards. In the past 15 years, there have been 105 gun-related homicides, claiming 167 lives. Most firearm-related crimes involve unlicensed users, though the Christchurch shooter reportedly held a firearm licence.

Advocates for tighter gun control say that stricter legislation is crucial for making our society safer. Removing semi-automatic rifles from society, they argue, reduces the risk of them being stolen and finding their way into criminal hands. What concerns many is the way we’re talking about firearms.

“We don’t want guns to be a symbol of everything that’s going wrong,” Hera Cook, a public health researcher at the University of Otago in Wellington, tells me over the phone. “We don’t want clutching onto your guns to be associated with asserting your rights as a rural person to live in a decent community and have a decent life.”

Cook has spent three years studying firearm culture in New Zealand, and is a member of pro-regulation lobby group Gun Control NZ. She believes that many conservative rural New Zealanders have been pushed further and further to the political right by governments that have underfunded their communities, while burdening them with excessive regulation and red tape. In the United States, powerful opposition to gun control is led by the National Rifle Association (NRA), and Cook is concerned that a similar style of politics around firearms has now taken root here.

“The [New Zealand] gun lobby,” she says, “has picked up NRA-style gun rights discourses, and those are incredibly negative and destructive.”

Cook tells me that, when tramping, she has noticed a change in people’s attitudes to those carrying guns in the hills.

“Up until the 2010s,” she says, “trampers felt that hunters might have a somewhat different culture, but you shared a hut and that was fine. I think we are now at a point where people are getting frightened of people carrying guns.”

This has been a recent change, she says, driven largely by mass shootings in the United States and the media coverage of these events.

“We are getting exposed to gun violence in a way that traditionally wasn’t the case,” she says. “And it’s terrifying. I think being frightened of individuals carrying guns is now sadly not that irrational. I think we have to strive to do something that’s actually not very rational, which is to keep being friendly and keep trusting each other.”

Cook dismisses the idea that there is a political agenda to remove firearms from private hands entirely.

“In the course of doing the research,” she says, “I have not encountered a single person who has said we should have a gun-free New Zealand.

“I feel quite comfortable supporting ordinary firearms users going into the bush and hunting. I have firearms users in my whānau. I think it’s part of our culture. What I don’t think is part of our culture is an NRA-style firearms lobby.”

[Chapter Break]

It’s been raining for weeks in Central Otago, and in Wānaka and Queenstown, shopfronts are sandbagged against the rising lake water that now laps the streets. This weekend, a steady stream of firearms is trickling out of the hills and pooling at collection points, where police wait to receive them.

At the Wānaka buyback, an elderly man arrives with a beautifully embossed antique double-barrelled shotgun that is still legal under the new laws. I ask him why he’s bringing it in, and he tells me his children aren’t interested in shooting and he doesn’t know what else to do with it. To my relief, officers advise him to take it to a local gun shop instead.

Soon after, a man turns up to hand in an enormous black military-style Heckler & Koch rifle. I’m told by the police officers who meet him that it’s his latest of several visits. He doesn’t want to bring in his whole arsenal at once, as he doesn’t want to advertise how many guns he owns. Such wariness is common at buybacks—I hear that people often drive hours to another town to hand in their guns, so their own community can’t bear witness to the extent of their personal collection.

At the Queenstown collection, I meet Sam Kernot, a young police employee overseeing the destruction of guns. He has a keen personal interest in firearms and military history, so I ask him how he feels about his current duties.

“I hate it.” He laughs. “The amount of really high-quality manufacturing that goes into a high-end firearm—it seems such a waste to put it through the crusher. We had an M1 carbine come in that had been in World War II, Korea, two Israeli wars and Vietnam. That’s five conflicts, one firearm. So the guy that owned that was really sad to be giving that over, and we completely understand.”

Nonetheless, he has been surprised at the number of military-style weapons the buyback has flushed out, such as AR-15-style rifles.

“The amount of ARs, and the style of ARs coming in definitely surprises me. The amount of customisation going on. The amount of high-capacity magazines floating around. The amount of guys coming in with super kitted-out attachments everywhere—really good optics. Why do civilians need these?

“When I see a farmer come in with a sporting rifle, it doesn’t surprise me at all, but when I see Joe Bloggs, who lives in town and who is a property developer, come in with five ARs, that seems odd.”

Kernot reaches into a nearby bin and pulls out a Browning .308 rifle with a wooden stock.

“This,” he says, “is a hunting rifle.”

He replaces it and pulls from the same bin a military-style Heckler & Koch rifle with a pistol grip and a heavy barrel shroud.

“This,” he says, “is the main battle rifle of the German military. This is a $10,000 gun. Why does a civilian have this? How does that benefit New Zealand? I’m not saying it’s wrong, but those are good questions, aren’t they?”

[Chapter Break]

Central Otago is a region at war. Every night, the enemy comes out of the hills to nibble tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of grapes. They move across the landscape in great, ravenous armies, devouring grass intended for stock, devastating crops and rooting up good farmland with their tusks and teeth.

Now, the old battle with deer, rabbits, goats and pigs has opened along a new front. Wallabies—already a pest in south Canterbury—are making their way up the Clutha Valley. And wallabies are going to cause as much trouble as the ongoing rabbit plague, predicts Doug Maxwell, a helicopter pilot and pest controller.

Maxwell, who has been flying choppers since 1974—the height of the deer-shooting era—takes me out to his hangar. Here his main tool, a two-seater helicopter, sits ready for action. In the locked gun cabinet are two AR-15s. These are not the highly specced, immaculately cared-for enthusiasts’ guns I’ve occasionally seen at the buybacks, but work rifles, battered and worn from thousands of hours of shooting.

Maxwell shows me a video of his work, filmed by a rifle-mounted camera. On a lake near Alexandra, Canada geese tumble from the sky in quick succession before the thumping AR. Maxwell has been allowed to retain his ARs because he’s a professional pest controller, but many of his friends and colleagues have not gained this permission.

“Farmers are by far the biggest pest controllers in New Zealand,” says Maxwell. “By limiting their weapons, they’re going to step back.”

He argues that military-style guns, such as ARs, are necessary for people in rural New Zealand because of their technology, which includes thermal-scope systems that allow a shooter to work in total darkness. These high-end rifles can quickly pick off hundreds of animals at long range.

“I would have said a few years ago you shouldn’t allow ARs,” he tells me, “but we’ve got a case for them as far as pest control goes.”

[Chapter Break]

In my adult years, despite the odd foray into the hills with Dad’s .303, I haven’t really embraced the hunting lifestyle. So, visiting Chris McCarthy, a professional hunting guide based near Lake Hāwea, is a reminder of where I’m from. McCarthy grew up on a nearby farm, and from a young age he knew firearms and hunting would be his profession.

“You’d be reading hunting books and sitting there, stuck at school, thinking, ‘I can’t wait to get out and do what those guys did,’” he says. “I would say early last century most people had a way or a link—an uncle, grandad or whatever—to get out on the land and hunt, and firearms were basically familiar to everyone.

“As we’ve become a more urban society, those links have faded and now we’ve got people who use them as part of everyday life, and people who know nothing about them.”

That’s where the friction comes from, he says: ignorance about firearms, about how people use them, and about how they open the door to a way of life.

“I think [firearms are] an integral part of New Zealand society. I just couldn’t see New Zealand without them. They enable us to harvest our own meat. They give us a reason to get out into those mountains. Not everyone’s idea of being in the mountains is walking from one hut to the next every day, looking at birds.”

[Chapter Break]

Firearms are a big part of life in southern New Zealand—there are almost 70,000 licence holders in Canterbury, Otago and Southland, compared with about 6000 in Auckland. Around 90 per cent of licence holders are male, although anecdotally this is changing.

In Queenstown, a training course for firearms licence applicants, run by the Mountain Safety Council, is full. There are about 16 people here, of all ages. Around a third of the people in the room are women—something instructor Shaun Moloney says is now typical in the courses he runs.

A young equestrian from Te Anau has come along with her brother. She says she doesn’t use firearms regularly, but needs to be able to in case she ever has to euthanise a horse.

There’s also a man looking to control rabbits on his lifestyle block, and a young mother hoping to put food on the family table.

Hunting, Moloney tells me, is not only a way to ease the financial burden of the weekly food bill, it’s a way for people to connect with their environment on a more profound level.

“A hunter’s relationship with the land is a lot more intense,” he explains. “It has another dimension. You’ve actually got the strength and the skills to go out to take an animal, and then the stamina to bring it back and put it on the table. That meal has much higher value than something you just picked up in the bargain tray at Pak’n Save.

“People want that, whether it’s a rabbit or a red stag.”

[Chapter Break]

When I return to Dunedin, my ears are still ringing from the chorus of disquiet over the new gun laws.

The national buyback scheme has finished, and anyone holding an MSSA without an endorsement is now breaking the law. Police report around 56,000 firearms have been handed in, at a cost of $100 million.

I pop into the new Gun City store that has recently opened on Cumberland Street. Behind the counter is the kind of hunting rifle that I, like Chris McCarthy, perused in Rod & Rifle magazines as a kid. The materials are modern, the scopes fancier, but the guns are the same.

The attendant passes me a Tikka .308 to try out. As I bring it to my shoulder and peer down the scope, I’m amazed at how light it is, how natural it feels in my hands. It’s a world away from that old Lee–Enfield I used to drag through the hills.

The promise of adventure transports me from this warehouse in industrial Dunedin to the mountains, and my imagination fills in the rest.

I bring the rifle down from my shoulder and, as I pass it over the counter, a feeling takes me by surprise: I’m reluctant to hand it back.