From Space

New Zealand through the eyes of astronauts

Gaze up into the sky on a clear night and you may glimpse small “stars” skating briskly across the heavens. Apart from their movement, they look just like any other stars, but watch them and they will often fade into invisibility long before approaching the horizon. In fact, they are man-made satellites, and at present some 700 roam the firmament.

Just occasionally, one of these lights passing in the night is a spacecraft manned by astronauts. It is curious to realise that other humans could be passing hundreds of kilometres above us, for the most part invisible, yet able to see the land we inhabit quite clearly. Indeed, astronauts have an unprecedented view of the Earth. As they circle the globe, their view encompasses entire countries and, from a vantage point far above all clouds and weather, the tops of thunderstorms and hurricanes.

Since the first manned space flights in the 1960s, astronauts have not just been admiring the Earth but photographing it, bringing a new perspective to geography and documenting events such as storms, floods, fires and volcanic eruptions. Their pictures have also recorded human impacts on the Earth such as city growth, agricultural expansion and forest clearance.

Astronaut photography fills a niche between aerial photography and imagery from Earth-observing satellites. The majority of satellite images are taken looking straight down at the Earth’s surface, and serve purely scientific or military purposes. Astronaut photography is different. Hand-held cameras are used, and many oblique views of the Earth’s surface are captured, often with the sun at a particular angle to highlight features not otherwise apparent.

Astronauts also record dynamic events, such as hurricanes, thunderstorms, squall lines, island cloud wakes and volcanic eruptions. Enjoying real-time communication with the ground, they can be given detailed information on where specific events are occurring. While many of the photographs they take have scientific worth, they also have aesthetic value. They are as much art as science. They portray the land, sea and sky in a way none of us is ever likely to see directly.

NASA is currently operating two programmes that allow astronauts to photograph the Earth. The first is the regular missions of the space shuttles. These reusable vehicles have been in operation since 1981, flying at altitudes ranging from 222 to 611 km above the Earth’s surface. Most recent missions have focused on the construction of the International Space Station (ISS), at an altitude of approximately 400 km.

The ISS programme has continued the tradition of astronaut photography. NASA has established a project called Crew Earth Observations to guide astronauts in hand-held photography from the ISS. An interdisciplinary group of scientists has selected some of the most dynamic sites on the Earth’s surface for particular attention. These include giant deltas in south and east Asia, coral reefs, major cities, industrial regions with heavy smog, areas prone to floods or droughts triggered by the El Niño cycle, alpine glaciers, tectonic structures, and features, such as impact craters, that may have counterparts on other planets.

One module of the station, the US Laboratory Destiny, has been fitted with a special Earth-observing window constructed from fused silica polished to telescope-standard optical quality. A reflective coating on the window absorbs ultraviolet radiation but transmits in the visible and near-infrared ranges. This allows photographs to be taken that show much greater detail than in the past. Film, digital and IMAX cameras have all been used to capture images through the window.

In those photos that show the blackness of space as well as the Earth, the one thing missing is stars. The films used are too slow, and the shutter speeds too fast, to pick up the small amount of light emitted by stars. Fast shutter speeds are required to eliminate blur, since the ISS orbits at 7.6 km/sec. Longer exposures are made only for photographing auroras, and in these cases stars are visible.

One of the great myths of the last century was that the Great Wall of China was the only man-made structure that could been seen from space. In fact, it is barely visible to astronauts even in low orbit. The wall is narrow and made from natural materials that blend into the landscape. However, many other human creations on the Earth’s surface can be seen without magnification, such as cities, croplands and forestry plantations. With telephoto lenses, much smaller features can also be distinguished, such as large buildings, highways and ships at sea.

Taken at an altitude of 300 km with a 100 mm lens, photographs have a spatial resolution of approximately 80 m. With a 250 mm lens at the same altitude, resolution improves to 30 m, and longer lenses enhance it further still. Most photographs have a resolution of between 20 m and 60 m. At a resolution of 60 m, urban areas can be discerned but not the details of buildings. More recently, images with spatial resolutions of less than 6 m have been obtained from the ISS. In these, bridges and country roads are visible, but a resolution of about 1.5 m is needed for the details of these features to be clear.

[sidebar-1]

The North Island is dominated by the colour green—light in areas of farmland, darker where there are forests. Prominent are Mounts Taranaki, Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe and Tongariro, all usually capped with snow. In the early morning astronauts see a great conical shadow to the west of Mt Taranaki, stretching to the coast and beyond. At this time of day the valleys are often full of mist, looking like the threads of a fungus spreading out across the landscape.

Human activities are also obvious. Within Auckland, the texture of the land varies from the close-hatched pattern of suburbs to the coarser white of central city office buildings and the green spaces of parks. Roads, especially motorways, are prominent, as are two marinas in the harbour. In the plantation forest areas of the central plateau, telephoto images show patterns of forest management, with the forestry compartments in various shades of green and brown reflecting the age and structure of the stands.

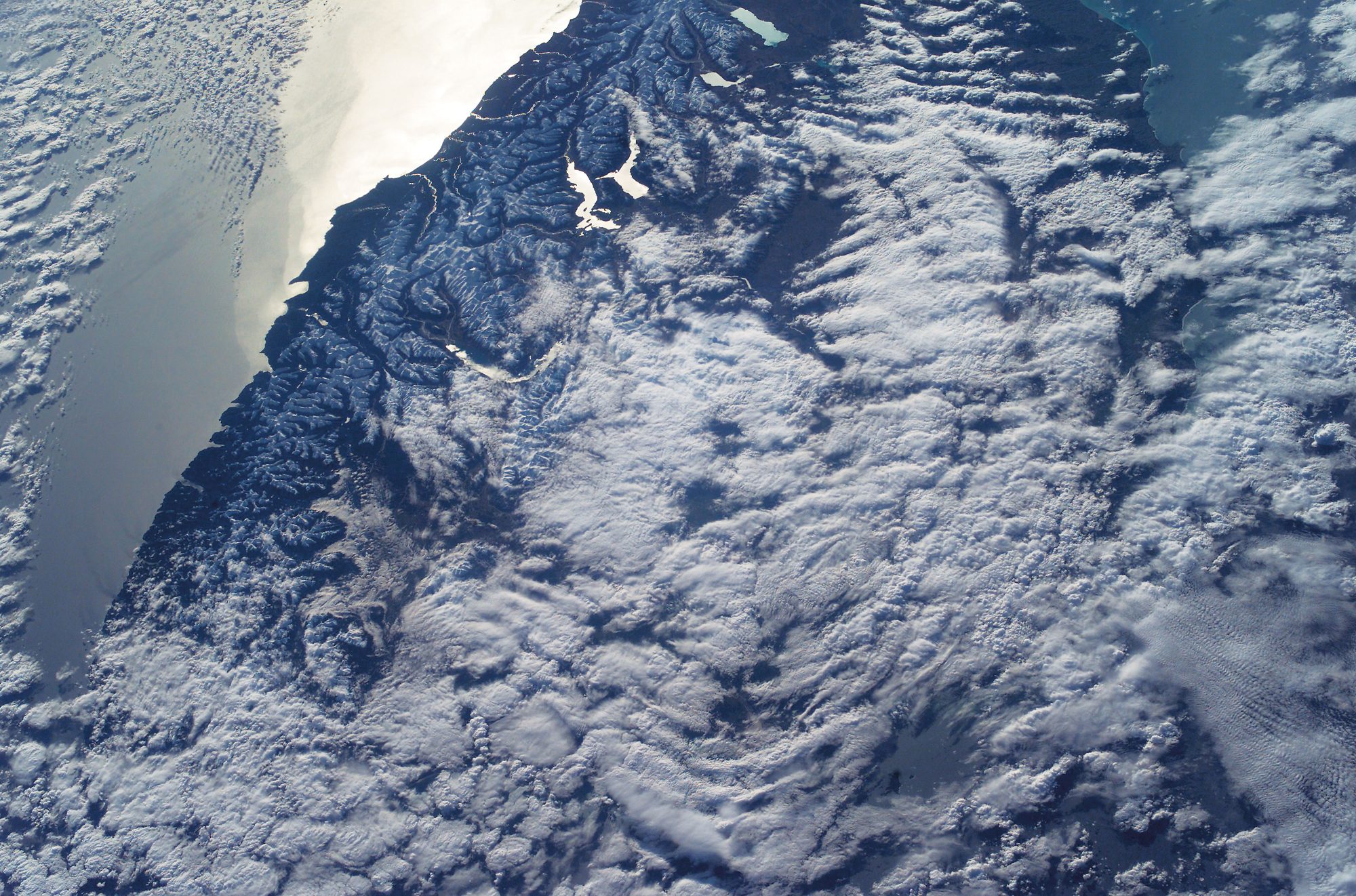

In the South Island, the colour of the land varies from shades of green in coastal and forested areas to brown and golden hues in drier and alpine parts and white along the axial tops. Just as tourists are drawn to the scenic beauty of the South Island, so is the eye of the astronaut. Nearly two thirds of the images in the New Zealand collection are of the South Island.

The most striking features of the island when viewed from space are the Southern Alps and the Alpine Fault, the latter extending in a clear line up the west side of the former. Periodically, snow cover is restricted to the ridges and summits east of the fault, making it particularly obvious. Further north, the fault curves east and splits, one limb running down the Wairau Valley, another in the direction of Kaikoura.

To the east of Aoraki/Mount Cook is New Zealand’s longest glacier, Tasman Glacier, flowing southwards for 29 km before melting into the braided Tasman River, which empties into Lake Pukaki. The lake’s brilliant turquoise colour is the result of “rock flour” ground by the glacier from the mountains and suspended in the melt water. Other lakes near by are darker in colour, although not uniformly so. To the east, alluvial fans formed by rivers eroding the Southern Alps have coalesced, creating the Canterbury Plains. Protruding into the sea, Banks Peninsula is the only recognisable volcanic feature in the South Island.

Otago appears as irregularly dissected blocks of hill country separated by basins, and not very green. Southland’s dairying and fat-lamb country shows up as a large green plain, contrasting with the ruggedness of Stewart Island to the south and Fiordland to the west.

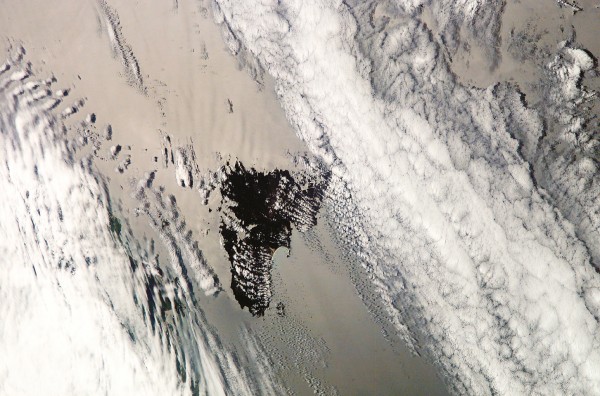

The space station also tracks over the subantarctic islands south of New Zealand. Auckland Island, 44 km long by 24 km wide, is host to the country’s southernmost and newest marine reserve. Mountains on the island rise to over 610 m, and the island lies as a windswept barrier in the path of the Screaming Fifties.

Next time you are basking on the beach, looking up into a cloudless sky, remind yourself that there could be a group of astronauts 400 km up in the International Space Station peering back at you, capturing another great image of New Zealand. Can they see you? Not with today’s technology. But in another few years, they’ll probably be able to update your mole map.