A Factual Geography (of cricket)

Somewhere, during my lifelong speculations on the History of the Future, the Science of Absurdities and the Geometry of Invisibility, I stumbled across a perfectly Factual Geography of Cricket. Even those who say they cannot get their heads around the simple notion that a cricket team is in until it is out, whereupon a second team goes in until it is out, and that this can happen four times in a contest that may last five days without achieving a result, would at least concede that climate, location, botany, landforms, migrations of people and a host of other geographical factors have an enormous influence on where and when this mysterious game is likely to be played.

Yet most Geographies of Cricket get their origins wrong. Cricket cannot have been a sport that by mere good luck evolved out of rough games with balls and sticks. I believe that, like football, it developed lovingly out of a deep human need to save open spaces near our habitations, whether we live in villages or in the most overcrowded of cities. A cricket ground is a lung that helps our homes breathe. The pleasures of cricket are huge, complex and varied, but none of them matches the feature we are most likely to take for granted: the largely unconscious physical and spiritual joy we take in the ground on which its dramas are played out. Cricket grounds have always been furtively and frequently sprinkled with the ashes of those who adore them.

Cricket is played on school and sports arenas, and sometimes even on dedicated paddocks, all around the country. Those grounds lucky enough to have a pavilion also gain a year-round sports focus and social centre. The stunningly beautiful Devonport Domain, which is the home of the North Shore Cricket Club, where I’m honoured to be a vice-president, has a pavilion that provides a score-box and changing rooms, a convivial meeting place for neighbours at weekends, a shelter when rain stops play and a hall for everything from parties to business courses to funerals.

Which leads me at last to the serious point behind the title of this essay. Three years ago the North Shore City Council commissioned a Review of Soil and Surface Conditions, Devonport Domain. It is a 51-page document, prepared by Richard Gibbs, working for a division of Recreational Services Ltd, and it comes complete with both drawn and modified-photograph maps, sample and illustrative photographs, tables and an electromagnetic scan. Anyone who still thinks there is no such thing as a Geography of Cricket is dreaming—just as anyone who believes that we can still look after our green playing areas by occasionally getting out a lawnmower and a roller needs to take a more practical interest in how their rates are spent.

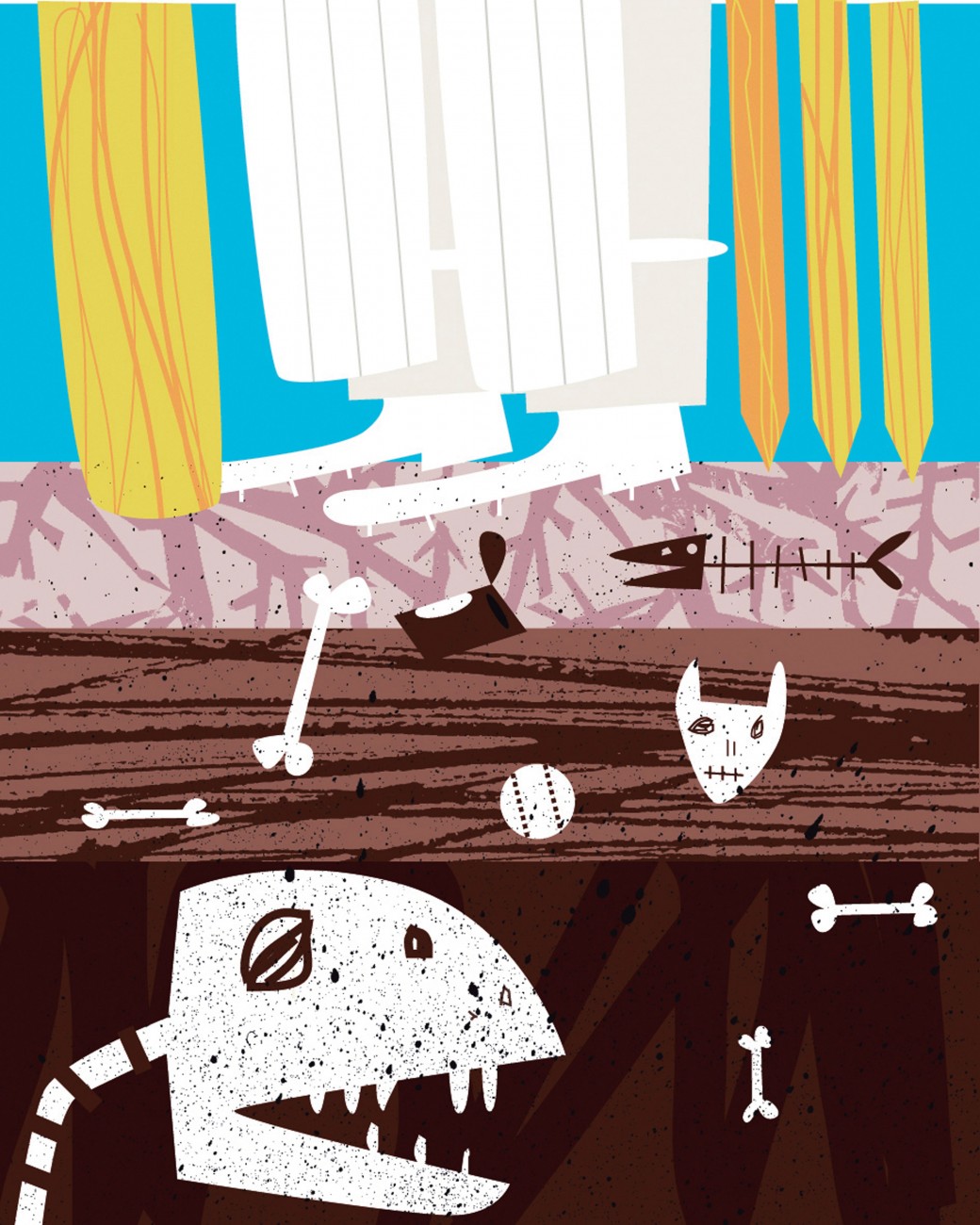

The document is nothing short of gob-smacking. Here is a history of land use laid bare—and all through the study of soils. It turns out that our domain was mapped in 1850 as a lagoon surrounded by swamp. It was filled in about the same time as nearby Mt Cambria was levelled for its wealth of scoria, and probably some of its rock and topsoil was dumped into the lagoon. Sand probably also got wheeled up from the neighbouring beaches. Those who lament the disappearance of several of Auckland’s volcanic cones for similar purposes have got a valid grievance. But I can’t help thinking as I watch Saturday cricket on this most magical of grounds that at least the community gained a great reward to balance out the loss.

And, incidentally, the technology is fascinating. Quite apart from the Review’s deep analysis of soil boreholes and laboratory tests, and the abstract pleasure of studying garish soil maps, there’s the boy-wonder of the machine, towed by a quad-bike, which “sees” below the surface. The Centre for Precision Agriculture at Massey University has come up with a sensor that measures soil electromagnetic conductivity to a depth of over a metre. It tells us what soils are underneath the spikes in your cricket boots, and the bike also carries a device linked to global-positioning equipment to give a precisely contoured picture of what wrongly appears to be an almost level playing field (a phrase I’ve never trusted).

Some of its conclusions can be quarrelled with, but there it all is—a living Geography of Cricket, and the scientific truth about what’s beneath bat and ball. There are a lot of questions to be asked before we throw more money at our wickets. And who would ever wish to be stumped for an answer?