Empire of the sea

The distant and remote Minerva Reefs—the closest coral atolls to New Zealand—have been the subject of political intrigue, a failed libertarian state and a naval showdown. Scientists believe they may also be the origin of some tropical species reaching New Zealand’s northern waters.

Roman gods have a flair for the dramatic, and few more so than Minerva, who emerged—clutching her mother’s weapons—from the head of her father Jupiter after it had been cleft by Vulcan’s hammer. In a similar way did Minerva Reefs miraculously emerge from the Pacific, two submerged coral atolls 500 kilometres from Tonga and three times that distance from New Zealand.

But therein the connection ends. The reefs are not named for the goddess of music, wisdom, commerce and magic, but for an Australian whaling ship that foundered upon the atoll in 1829. At that moment, the human and natural histories of the reefs divided at the waterline.

The atoll of North Minerva rises to an elevation of just 90 centimetres; the southern atoll—actually two atolls, joined at the hip—is a fraction of that, and regularly awash. Despite the very modest prominence of the reefs, they have nonetheless been at the centre of a major political battle for nearly four decades.

In 1971, Las Vegas real estate developer Michael Oliver began dumping barges of Australian sand onto North Minerva, making an island out of an atoll, then a state out of thin air. The Republic of Minerva declared independence on January 19, 1972, with a view to generating its gross domestic product by registering cargo ships under a flag of convenience. A stone tower was constructed, a flag hoisted, and coins minted (with a face value of $35).

By June, the occupiers forced the hand of Tonga’s King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV. He annexed Minerva—claiming the reefs as traditional fishing grounds—scribed a 12-mile territorial limit around them, then visited in ships with 100 troops to dismantle the republic’s structures, and a four-piece brass band to play the obligatory national anthem. Oliver’s brief reign was over, though he would later attempt to establish libertarian states in the Bahamas and Vanuatu. Both failed.

Tonga, too, would have its share of trials, facing challenges for the territory that still rage today. When the kingdom claimed the seabed 200 nautical miles from its coast under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Minerva Reefs suddenly became politically relevant, overlapping with Fiji’s claim under the same treaty. Within the disputed region lies thousands of square kilometres of ocean and mineral deposits on the seabed potentially worth hundreds of millions in mining licences. This led to a naval stand-off, with the Tongans erecting a navigational beacon, and the Fijians tearing it down. Last year, Tonga suggested a land swap—Minerva Reefs for the Lau Group, which represents about half of Fiji’s territorial sea and would almost treble that of Tonga. The suggestion wasn’t taken seriously, and did little to settle international relations.

This, the turbulent history of the upper one-metre of Minerva.

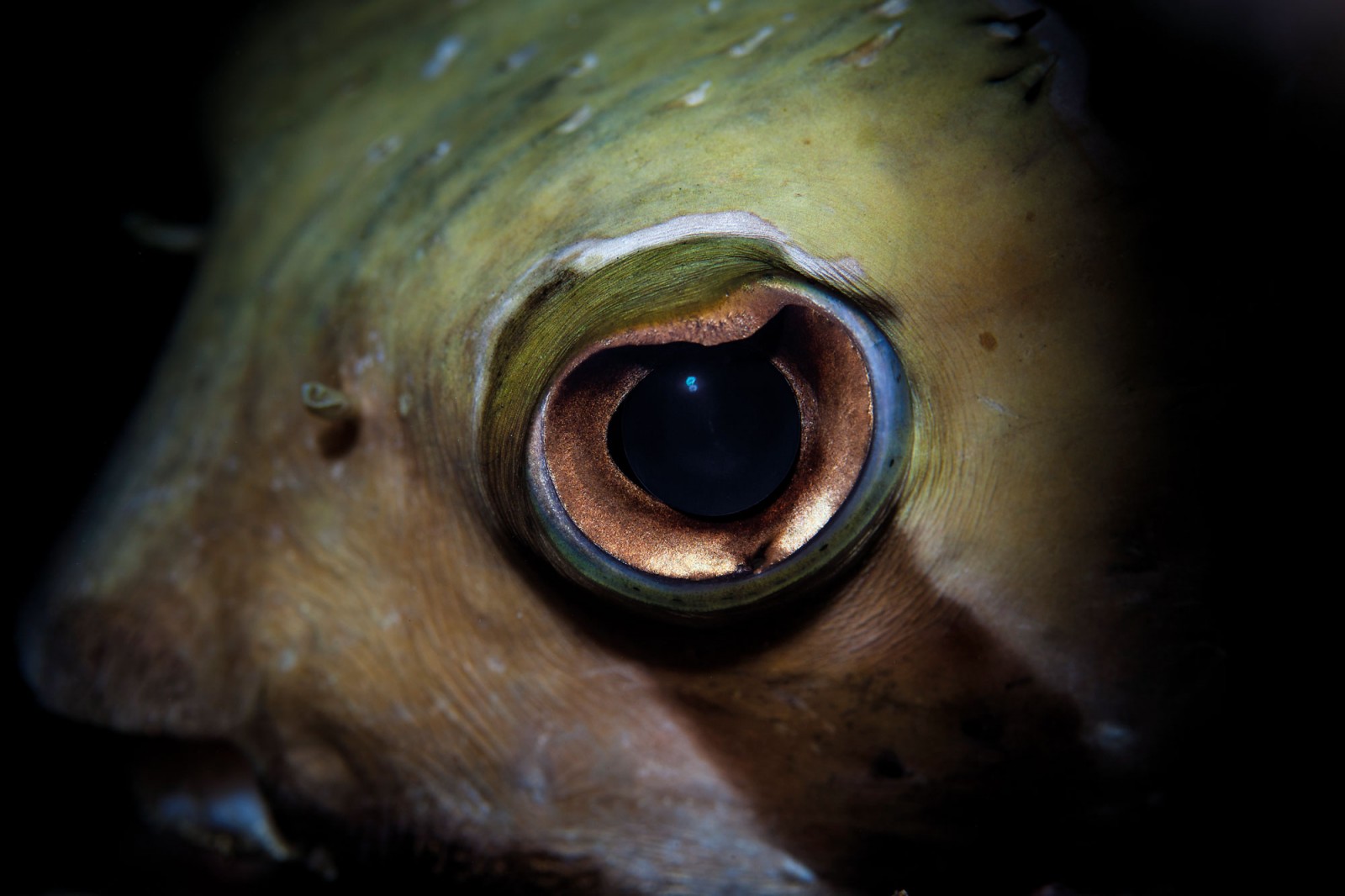

Below the heaving waves of the Pacific, however, history has played out rather more quietly. Atolls form about the rim of a seamount or volcano that has subsided beneath the surface. One coral polyp upon another, a circular reef grows, ever upward towards the light, life upon death. As the atoll grows, it’s enlarged also by larvae drifting on ocean currents. Algae, anemones and soft corals accompany the reef-building structures. Fish are attracted, as are the host of predators—from large reef fish to sharks.

Lying on the 24th latitude south of the equator, just shy of the Tropic of Capricorn, Minerva Reefs are the closest coral reefs to both New Zealand’s Exclusive Economic Zone and the northern-most outpost of our territory, the Kermadec Islands. Because there are no firm barriers to dispersal in the sea—like mountains or rivers that limit the dispersal of species on land—one might presume that the bulk of tropical larvae drifting into New Zealand waters comes from this closest tropical source, but this is not necessarily true. The Inter Tropical Convergence Zone—also known as the doldrums—is an invisible wall of sorts, the lack of wind and currents dramatically limiting the passage of larvae southward. In addition, the predominant current to the south is the Tasman Front, a slow-moving extension of the East Australia Current that flows from New Caledonia, down the eastern coast of Australia and across the Pacific to reach New Zealand’s northern waters.

“All our tropical species are from the west; that’s the null hypothesis,” says Tom Trnski, head of natural sciences at Auckland Museum. “But the distances are quite large, and recent studies have shown that it could be more complicated than that.”

There appears to be “a periodic ‘relaxation’ of the Tasman Front,” says Trnski, “where it stops pumping and creates an opportunity for the larvae of tropical species to arrive in New Zealand waters from the north, from places like Minerva.”

DNA analysis on crown of thorns seastars and tropical collector urchins by Libby Liggins of Massey University determined that seastars and urchins at the Kermadecs were no more related to their Australian cousins than individuals to the north and east.

The finding suggested a less “cut and dry” pattern, says Liggins. “There’s a tendency to focus on average patterns and predominant currents, but the ocean and the reproduction of marine organisms can be extremely variable in space and time.”

Tropical cyclones can drive the dispersal of marine organisms, and larvae appear to have a surprising level of control in their own right—swimming against or across currents, aggregating with their own species, even adjusting their depth in the water column.

Whatever the case, larvae are playing a game of long odds. Liggins estimates that the majority of larvae perish prior to settlement on tropical coral reefs, in some cases more than 99 per cent. And their chances just get worse on arrival in New Zealand.

“Here they have to settle on rock rather than coral, there are different food sources, different predators, new competitiors, not to mention the colder water. The odds are certainly stacked against any larvae lucky enough to make it to our shoreline,” says Liggins.

To better understand the migration pathway for tropical species, Trnski led an Auckland Museum expedition into the South Pacific this year with New Zealand Geographic photographer Richard Robinson. It was supported by the Australian Museum and the Tongan Ministry of Environment, eager to increase their scientific understanding of this remote outpost of the kingdom.

In just four days at Minerva Reefs, the scientists recorded four dozen species not previously known at the atoll, increasing the known species distribution by nearly 20 per cent. It was an indication of both the biodiversity of the reefs and the lack of scientific attention they had received to date. Scientists also noted fewer sharks, fewer large migratory fish, and fewer big reef fish such as grouper and coral trout than at the Kermadecs. It was evidence, says Trnski, of reasonably intensive fishing, from both recreational fishers en route between Tonga and New Zealand and possibly also Tongan and Fijian fishers frequenting the reefs.

Climate change is strengthening the East Australia Current and Tasman Front, and increasing the frequency of tropical cyclones, bringing warmer waters and more larvae to our coastlines, likely driving an increase in the tropical species visiting and abiding in New Zealand’s northern waters. Like the seastars and urchins, the route they take to reach our shores will be written in their DNA.

Biopsies of fish taken from Minerva Reefs will be analysed and compared with samples of the same species from both east Australia and the Kermadecs to gauge the extent of interaction between the marine regions and understand the shifting nature of the currents that connect these distant shores.