Earth, the home of mankind

There were no clean hands when Jill and David Moorhouse’s neighbours joined them to restore a 19th century earth building on their farm in the Awatere Valley, near Blenheim, Today, many of those early “cob” dwellings are still standing, and earth building is enjoying a renaissance as a new generation discovers the magic of mud.

Down a gravel road come farming families’ cars. It is Easter and the weather is ideal for mending mud huts. The air still has enough heat to dry the clay mixture. But the scorch of summer has passed, so the mud will not dry too quickly and crack.

Another good point: all the children are home from school. In time they may take over their family farms and become responsible for old, squat-walled homesteads and outbuildings made of earth. So, if they enjoy the mud-pie work that lies ahead of them today, they are likely when they grow up to care for their own share of the little-known treasury of mud houses that lies up and down the eastern side of the mountain ranges of the South Island.

The cars on the gravel road are heading for Dumgree station in the Awatere Valley just south of Blenheim. The visiting families’ old earth buildings all need repair, and today’s job is the start of a cooperative round of work which should see five families coming together to restore cob buildings on their own properties.

“Cob” is the South Island word for earth used as a building material, though it is actually just one of many earth-building techniques. In the harsh, isolated, treeless heads of valleys, earth was not merely the only building material on hand for early settlers, it was also free.

Once, New Zealand had about 8000 mud buildings, but they were seldom meant to last.

Last they did, though. And because the walls of cob houses were 40 cm to 60 cm thick—you cannot pile up mud in skinny wafers—they stored the warmth of winter fires, and kept out the worst of summer’s heat.

But mud was not chic: too rough, too dumpy, too peasant-like. So when the wealth of great wool cheques rolled in, station owners set up brick kilns, opened quarries and hauled in timber for houses that would astonish the neighbours and inspire a frenzy of mansion-building.

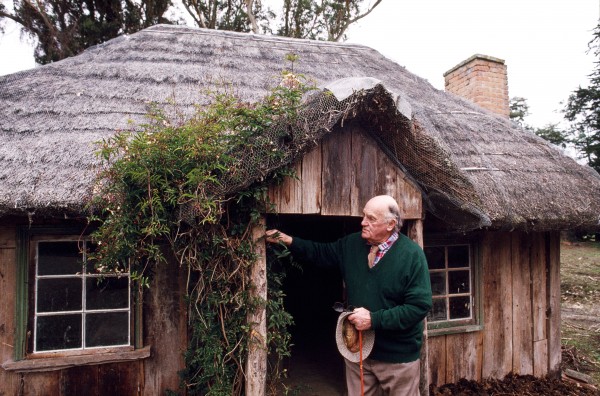

This is what happened at Dumgree. The owner, Dr Thomas Renwick, built a quick cob hut, probably in 1849, and the family followed it up with a grand brick homestead. In time, the chauffeur was put in the hut. Full-time gardeners tended a begonia house, lily ponds, a rock garden, flower borders and lawns on which garden-party guests raised their hats and twirled their parasols.

Today, nothing marks the homestead except the crumpled frame of the begonia house, the abandoned rock garden, the newly rediscovered lily-pond outline.

And the chauffeur’s mud hut.

Getting the hut ready for repair takes work. Especially important is the job of clearing away earth and leafmould from around the base, and then digging out a trench to expose the stone foundations. Until that is done, soil and leafmould act as a wick that carries soil moisture up past the foundations and into the cob wall.

This is a common peril. Rain or soil moisture can destroy earth buildings. A landslide some time before 1878 short-circuited the stone base of New Zealand’s oldest and best known earth building, Pompallier House at Russell in the Bay of Islands, and caused damage which only now the Historic Places Trust is expensively repairing.

Once the volunteer workers at Dumgree are ready, final restoration begins on the outer face of the walls. The surface is brushed and sprayed. Wheelbarrow-loads of mud laced with cement and plasticiser are pressed into cracks. More layers of mud are pushed on and smoothed. And after a few hours the workers are able to stand back and admire walls that again look as they must have done when new.

Further south from Dumgree, close to the coast but hidden from the sea, a different collection of cars arrives to inspect a range of farm buildings probably built before 1868. The buildings form two sides of a country garden, and the visit is another school-holiday pilgrimage, this time open to anyone interested in cob buildings.

The walls have the same squat look of the 1849 but at Dumgree, the same uneven surface, the same extraordinary thickness that gives the buildings an entirely foreign look—so thick that often in a cob house the windowsills can be broad enough to be used as window seats.

The two outbuildings stand in the Kekerengu Valley north of Kaikoura. Both were part of the estate of the Hon. John Dresser Tetley, who was said to be able to ride 70 km in one direction and still be on his own property. Six house servants waited on the Tetley family. Privately imported parsons taught the employees’ children to spell and to pray. But the parsons made a botch of straightening out their master. As Tetley sank in debt he swindled banks and merchants out of £60,000, then fled in disgrace to Uruguay.

In the district, Tetley’s name is still remembered for some sort of naughtiness. But—as at Dumgreethe homestead is obliterated. The grandeur has melted away, and all that remain are a long, low cob building that served as a travellers’ accommodation house, and a cob cottage in which Tetley’s head shepherd once raised 11 children.

On the way back from Kekerengu, the cob pilgrims call on another earth building. This time there is no doubt when it was built. Over the front door a terracotta plaque bears the date: 1991.

So, just when a small but growing group of enthusiasts is travelling the country saving old cob buildings, new families are building new earth houses and learning about the uncreaking calm of their interiors, the strong enclosing feel that thick walls bestow and how steady the temperature can be when walls are around 40 cm thick instead of 13.

Not that there is a great landslide of new earth housing: countrywide, the average is about 30 houses a year.

The area with the greatest concentration of new earth houses must be the small rectangle of land west of Blenheim lying between the road to Nelson and the Wairau River.

Here, in the heart of the Marlborough winegrowing area, freshly built mud houses and wineries stand among their predecessors from last century. The owners all sound enchanted with them.

“We love our house. It’s so peaceful and solid,” says Keren Mitchell. As young people, she and her husband lived in massive-walled houses of cob and limestone in the Canterbury and Marlborough high country.

Later, the solidity of convict-era stone buildings in Tasmania added to their enjoyment of solid structures made from local materials. So they decided, in her words, on a house that would blend into its surroundings as if it had grown up out of the ground.

The Mitchells settled on sundried bricks, but chose to make them extra-large-75 kg each, instead of the usual 18 kg. Marlborough is earthquake country, and at first the Mitchells thought of steel reinforcing, but finally turned to a timber frame. The house is virtually a pole building with brick infill.

Rough-textured and honey-gold, the bricks of the Mitchells’ house so much appealed to Philip Rose, their neighbour over the road, that his company, Wairau River Wines, was won over to mud for its restaurant, shop and tasting room.

If anything, the choice has been too successful. Customers, says Philip Rose, think the building “absolutely marvellous.” They take photographs, gasp at the thickness of the walls, feel the texture of the bricks—and drive off forgetting what they had come to buy.

Rose tosses one of his “only-joking” laughs into the air, and adds the comment that customers from as far afield as Auckland and Queenstown have gone off saying that they too want to build in earth.

A few kilometres east, Allan Scott Wines also has a new earth restaurant, tasting room and shop. Scott was attracted to earth because of the feeling of permanence, and says he expects his building to be still standing in 200 years.

Inside and out, it has a smoother surface than that of the Mitchells’ house or the Wairau River Wines building, because it was built of earth tipped into formwork and rammed hard. So the walls are all of a piece rather than raised block by block.

Even so, wall surfaces still have a slightly uneven handcrafted appearance and, says Scott, the more you kick them the better they look. Better or not, his walls should be able to survive a few scuffs over the centuries. They are 45 cm thick and solid all the way.

He especially enjoys having a building the colour of the land, and feels that it has a personality which factory-made materials cannot match.

Near the western edge of the wine district, Jane Hunter, managing director of Hunters Wines, lives in a restored earth house which she thinks is 96 or 97 years old. “It has such a warm feeling,” she says. “So quiet. Everyone says what a wonderful feeling it has.”

Then she mentions the even temperature inside earth houses.

And this is the heart of the matter. A 40 cm wall of earth can keep out an awful lot of weather.

During winter, many South Island households keep wood-burning heaters running non-stop for five months. In my own mud house, 21 km south of Blenheim, I can heat a vast open-plan living area with just a few electric heating cables set in a small area of concrete floor. I switch them on between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m., when electricity is half price.

Twelve hours after the floor heating has switched itself off, visitors look around to discover where the comforting warmth is coming from. Not until sunset do I need to light a wood-burning heater.

This is a welcome economy. But it offsets an earlier expensive economy. The house ran ruinously over budget because of design flourishes that slowed construction and demanded elaborate steel reinforcing.

Not that earth houses have to be dear, or even reinforced. Do-it-yourselfers, if they ignore the value of their own time, can create amazingly cheap houses. In Todds Valley, near Nelson, Bella and Richard Walker spent $15,000 in the mid-1980s building their 70 sq m house out of sundried bricks they made themselves. Their ideals dictated the very minimum of noise or machinery in the construction. So they managed with a grubber, a wheelbarrow and a mould for the bricks.

The result is a look of proud hand-wrought simplicity, with the variations in the bricks fitting in well with the roughsawn timber that the Walkers used.

Those who lack the time or inclination to do every laborious little task themselves can buy ready-dried bricks from commercial makers in Nelson, Northland, Opotiki, Auckland and Central Otago, or they can employ people to do the job.

People who use a chequebook as their chief building tool get two other choices, but end up with less of the wiggly handmade charm of the typical cob house.

For them, the simplest choice is to have a house built with compressed soil-cement blocks, either made to order or made by workers on the site. In either case, a steel mould which has a moveable end attached to a lever is filled with a mixture of soil, sand and cement. The lever is pressed down, squeezing the mixture tight. Then up goes the lever and out comes a smooth, accurate, rain-resistant block, already hard but needing time to be slowly dried out before a blocklayer can build with it.

Their other option is to find a builder who works with rammed earth. These are a rare breed. In the South Island, the only practitioner who comes close to being full-time is Graham Perry, of Spring Creek, near Blenheim.

Perry, a drainage contractor by background, first started thinking about earth building during a hunting trip to the Awatere Valley. He and his companions stayed in a hundred-year-old cob shearers’ cottage. “It was the middle of summer, but that but was so cool,” he says. “began thinking, ‘Why can’t we build like this today?”’

In tossing up between adobe and rammed earth, Perry chose the latter, primarily to save his back. “Adobe bricks can be very heavy,” he says. “I didn’t fancy lugging them around all day.”

Instead, Perry follows his own updating of the methods which Marist priests and brothers brought to New Zealand when they built a print-shop and tannery for Bishop Pompallier in 1842.

The Marists, plus their architect, Louis Perret, came from around Lyons, where the Romans built a city of rammed earth. Today in the Lyons-Grenoble areas, mud churches, chateaux, factories, apartment buildings and farmsteads are not only common, they remain socially acceptable. And the University of Grenoble is a centre for research and propaganda for earth buildings—sometimes to the amusement of African countries where earth is the universal building material, but which university lecturers think ought to benefit from French research.

“Where will they stop?” asked one African diplomat being conducted over a display of earth buildings between Lyons and Grenoble. “Now they want to show us how to build our huts.”

Graham Perry’s adaptation of the Lyons/Grenoble/Pompallier method takes account of earthquake fears and of engineers’ unfamiliarity with an earth wall’s ability to stand up.

Into a trench dug for perimeter foundations he drives second-hand railway lines. My own house had 53 of them sunk with a pile driver and then anchored in reinforced-cement foundation beams. Except where giant rocks defied the pile driver, each railway line is sunk in 1.5m of boulders and reinforced cement.

Shuttering 1.5m high was then clamped on to the foundation beams, and a mixture of subsoil, sand and cement was combined with a rotary hoe. A front-end loader dumped the slightly dampened mixture into the shuttering, and men armed with hydraulic rams compressed the material.

So quickly can soil-cement be compressed into walls that once the formwork is filled and the mixture rammed tight, the shuttering can immediately be taken away, lifted and clamped on to the bit of wall that has just been created within it.

Once all the walls have been completed, a continuous reinforced-concrete beam was poured on top of the walls to tie them all together, in the same way that a timber top-plate holds together a timber-framed house.

Clearly, this is not the cheapest way of building. Graham Perry ranks it alongside a timber house built to the highest standards.

In New Zealand, soil-cement walls were pioneered by P. J. Alley, a brother of Rewi Alley. P. J. Alley, who taught engineering at Canterbury University College, hated the thought of rimu forests being turned into the unseen studs, joists and rafters of timber houses. And, in the days before timber preservation of today’s standard, he had no faith in radiata pine.

Being a Canterbury man, Alley had grown up surrounded by cob houses: the 1867 census recorded 2425 Canterbury earth houses. And he knew—as who doesn’t—that water washes soil away. His experiments showed that an unplastered wall of Cashmere Hills loess soil mixed with 10 per cent cement and pea gravel used as an extender would not be washed away even after prolonged squirting with a hose.

After he had published the results of the experiments he performed in the 1940s and 1950s, a few houses were built in soil-cement, though only after their owners had overcome difficulties in getting building permits and an even greater difficulty in raising loans. The State Advances Corporation simply turned applicants away, and local councils were less than enthusiastic.

Graham Perry reports that he had no trouble borrowing from the Housing Corporation for his own soil-cement house. But Anneke and Bram van Huizen, who built in Blenheim using soil-cement blocks far greater than the usual size, ran into trouble getting a building permit. A man at the council office told them: “People shouldn’t live in mud houses these days.”

Miles Allen, who earned a Master of Architecture degree for studies on earth buildings, scoffs at such remarks.

Earth buildings came crashing like a revelation into Allen’s consciousness. He had just completed five years at Auckland University’s school of architecture learning how steel, timber, bricks, glass and reinforced cement are used. Then, with a new bachelor’s degree in his pocket, he discovered that soil is the world’s most-used building material and realised that the education he had been given had perpetuated students’ ignorance about how at least a third of mankind houses itself.

Around the world, mud buildings come in almost unbelievable variety. They have, after all, been used for 9000 years, and in that time they have been adapted to suit climates, religions and the ways people live. They have also had time to prove their durability: 3000-year-old remains still exist in Iraq.

In the United States Southwest, Pueblo Indians built enormous structures up to five storeys high with as many as 2500 rooms which served as a block of flats to house an entire community under one roof. They were built in a similar way to that of South Island cob houses: by dumping handfuls of a wet clay and straw mix on top of one another.

Pueblo buildings 900 years old are still lived in, but their cob method died with the arrival of Spanish colonists, and the change came because Spain itself was once an Arab colony. Invading Moors introduced Spaniards to sundried bricks, which in Arabic are called at-tub or al-tub. The word became adobe in Spanish, and when Spain colonised the Americas adobe overwhelmed Pueblo methods.

Spanish mission churches are today venerated, and modern adobe houses are fashionable—and expensive. At Santa Fe, New Mexico—a state which boasts some 60,000 adobe dwellings—a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright cost more than a million US dollars to build. Nathaniel Owings, a partner in the New York architectural practice Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, champions of the glass-clad skyscraper, built his own dream house not of steel or concrete, but of the humble mud brick.

In North Africa, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, towery cities of mud buildings survive within protective ramparts of adobe. In areas where the fashion for domed mosques did not take on, the roofs of mosques are constructed like fanciful forests of jutting stalagmites.

The tallest earth building I have been able to trace is a 10-storeyed apartment house in South Yemen (though in all likelihood the Tower of Babel was earth-built), and once I had the thrill of treading carefully across trembling floor joists nine storeys up in an abandoned Himalayan palace built almost at the altitude of Mt Cook.

No wonder, then, that Miles Allen felt so disappointed that a long, expensive education had kept him ignorant about an adaptable and durable material that is still in widespread use among less “learned” people. To patch up this gap in his knowledge he tried to track down every earth building in New Zealand. His tally so far is 560 still-complete buildings, of which 240 are houses.

They range in size from a tiny but at Waimate called the Cuddy to a two-storeyed homestead just north of Timaru which has a splendid staircase for the family next to a set of lesser steps for the long-gone butler and his staff.

The Cuddy (see page 42) has a shrine-like status among cob cobblers, the group of South Island mud-lovers whose passion and hobby is the restoration of old earth buildings.

The cardinal of all cob cobblers is David Studholme. Eighty-one years old this year, he started his long career in cob building on the Studholme family station, Te Waimate, where the Cuddy stands.

The Cuddy is a wattle-and-daub building. Wattle, from which the Australian trees take their name, originally meant a strip of woven branches, usually acacia. If wattles are made with gaps for windows and doors and are then attached to uprights planted in the ground at each corner, the result will be a framework that will act as reinforcing for walls made by slapping or daubing wet clay on either side of the wattles until all gaps are filled, and then building up the surface by daubing more clay until the walls are as thick as required.

The Cuddy was David Studholme’s first restoration job. He had no guidance, no written instructions, nothing but commonsense and an ability to keep learning from experience. By now he has led teams of restorers on more than 20 jobs, and admits that outsiders think cob cobblers strange because they will travel 500 km or more without pay to get themselves dirty fixing old buildings they do not own.

Amoeba-like, his original team has multiplied by splitting into regional groups that share his knowledge and spread his message. The group that supervised the patching of the Dumgree chauffeur’s cottage was led by two Blenheim teachers, John Davies and John Orchard.

John Orchard calls himself a Studholme disciple, and at the end of the day’s work at Dumgree he was glad to see that the five farming families had in one day learned enough to become an independent group. Not that everything about earth building can be understood in one day. David Studholme himself says he is still learning, and insists that people who think they are experts are only fooling themselves.

One of the reasons has to be that earth buildings can be put together in such a variety of ways.

Cob is the simplest method. A layer of mud is heaped on the foundations, and when it has dried enough to carry more weight another layer is added. As in other earth buildings, it is essential that the upper layer of humus and topsoil be kept out of the mix used for building, though tussock, snowgrass, horsehair and chopped up lengths of barbed wire can be added as a binder. Before the walls dry too hard, a spade or a big two-handled cob knife is used to slice away surplus mud and form a flattish surface.

Wattle and daub we know already. Lath and plaster is a variant in which light lengths of timber are laid horizontally but not woven. Cob and ricker is similar, using light boughs instead of dressed timber: ricker comes from the word for a kauri sapling.

Sundried brick is a favourite method where rainless weeks can be guaranteed while the bricks are exposed for drying, though plastic sheets or a temporary open-sided shed can save bricks from being destroyed by sudden rain. In Central Otago, sundried bricks were used in most surviving buildings. Pressed bricks are a modern alternative. The handcrafted look is sacrificed, but the method has special advantages for do-it-yourselfers. Blocks can be made in snatches of spare time before the months of serious building begin.

Turf or sod construction was another Central Otago favourite. Specimens still survive there, even though they were not meant to last. Goldminers, moving from rush to rush, dug out roughly squared off lumps of topsoil and grass and laid the lumps in a row. Often one layer of sods was cut and placed so that the edges of individual pieces sloped left to right, with the next layer angled right to left to produce a herringbone effect.

Half-timbering was the way Tudor cottages in Britain were built. First a framework was erected out of big unsawn boughs roughly adzed. The straightest pieces formed the uprights. The less straight were attached, criss-cross, between the uprights and secured to other baulks of timber by mortice joints or dowels. This left big empty triangular spaces which were filled with mud. A surprising number still stand in New Zealand, but often the work is hidden by weatherboards added later.

And what of the future? Earth builders and designers report rising interest in both brick and rammed earth styles.

Graeme North, a Warkworth architect who helped launch the Earth Building Association of New Zealand (EBANZ) four years ago, believes that a concern for environmental integrity and energy efficiency will steer many more people back to the earth. He lists local, nontoxic building materials, thermal performance, low maintenance, durability and aesthetic considerations as major advantages of building with earth.

He also thinks that earth building has a strong philosophical appeal. “There’s a deep attraction in the idea of digging up your back yard and building a house out of the soil,” he says. With an engineering design code for earth building well on its way to completion—”engineers are vital to getting earth structures built,” says North—nothing should stand in the way of people wanting to build their dreams in earth.

For the moment, though, economic considerations may well have the last word. For all his enthusiasm, even Miles Allen has limited expectations. He does not expect earth to be used in more than a few per cent of New Zealand houses. Not because of any inherent weakness in soil as a building material, but because of overwhelming pressure to use timber, concrete, sheeting, steel—all of them materials that can be marketed profitably.

Who could make money by advertising dirt?