Deep history

Beneath the waters of Lake Waikaremōana is a lost world, a 2000-year-old tableau of the lake’s surprising origin.

Waikaremōana, the many-armed lake at the edge of Te Urewera, in the eastern North Island, offers a tantalising glimpse of how things were before humans arrived in Aotearoa. Its waters contain mysteries and memories, some ancient, some recent, many of them now coming to light. Millions of years ago, mountainous Te Urewera, like most of the landmass geologists now call Zealandia, lay under the sea. The forest-clad hills we see today are marine deposits of silt and sand, lifted and tilted by the tectonic forces that have shaped Aotearoa.

During that long tectonic journey, there was no Waikaremōana. No lake at all, just steep ravines with swift-flowing rivers scouring through the rock strata. Then, 2200 years ago—around the time that Hannibal was crossing the Alps, the Romans were building the first sundial and the Chinese were inventing tofu—something dramatic happened. Two landslides carrying millions of tonnes of fractured sandstone and siltstone swept down from the mountains, converging to produce a wedge some eight kilometres long and four kilometres wide that blocked what is now the Waikaretaheke River. Slowly and steadily the valleys backfilled with water, producing a lake that is 256 metres at its deepest point—the deepest lake in the North Island.

Remarkably, many of the trees that were living at the time Waikaremōana was formed remain preserved by the lake’s waters as a forest frozen in time. Their leafless crowns still stretch towards the sky, beckoning not birds but fish to flit through their naked branches.

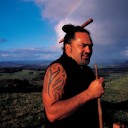

This, at any rate, is the geologists’ story. There is another story of the lake’s origin, far more evocative and disturbing. It is the one told by the lake’s indigenous people: Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Ruapani and Ngāti Kahungunu.

In their account, a father, Maahu, asks his daughter, Haumapuhia, to fetch water from a pool. The girl declines. In a silent rage, Maahu picks up a gourd and goes to the spring himself. The aggrieved father sits there brooding for a long time, and eventually Haumapuhia goes to find him. His wrath rekindled by the sight of her, Maahu seizes her and thrusts her head into the pool to drown her.

In her extremity, she calls upon the spirit beings of the ancestral world, who transform her into a taniwha. With flailing strokes of her arms and legs she gouges deep furrows in the earth as she attempts to escape—first to the west, then north, then east. But mountain ranges block her path in each direction. Finally, she senses the presence of the ocean, and turns south-east, making a final bid for freedom through what is now Onepoto Bay and down the Waikaretaheke River.

Alas, her journey is short-lived. She is turned to stone, her sacred form preserved forever in the rocks of the river. At least, it would have been preserved forever had not a slip come down and buried her, just before the water of the Waikaretaheke was diverted for a government hydroelectric scheme in the 1920s. The taniwha’s resting place is now as hidden as the drowned forest.I carry both stories in my mind as I lift my kayak into the water at Mokau Inlet, one of the northern arms of the lake, and paddle westward. I have come not just to explore the physical lake and its sunken treasure, but also to take a dive into the lake’s more recent, human history.

I’m grateful that I’m experiencing the lake in high summer. Photographers Irene and Crispin Middleton made some of their sorties here in the depths of winter, when they figured planktonic algae would be least abundant and the underwater visibility greatest. On some mornings, they had to scrape ice from their boat, and the water temperature was a bracing seven degrees. They pumped dumbbells to warm up their muscles before making a descent. During one dive, a seam in Irene’s drysuit split, flooding her with frigid water up to her chest.

But the enchantment of floating silently through the underwater treescape—this “serene catastrophe”, as Crispin put it—far exceeded the discomfort.

“It was so quiet and still,” Irene said. “Diving in the sea, there is always the background noise of creatures moving and eating. You don’t get that in a lake.”

What you do get are the crowns of ancient trees looming out of the turquoise depths, reaching towards you like hands. An exceptional sight in a singular landscape with a unique personality: Te Urewera.

[Chapter Break]

Everything changed for this landscape with the passing of the Te Urewera Act of 2014, which established Te Urewera as a legal person. Can there be any legislation in the world that opens with words as moving and majestic as these?

“Te Urewera is ancient and enduring,” the act declares, “a fortress of nature, alive with history; its scenery is abundant with mystery, adventure, and remote beauty.”

Standing at the lake edge in moonlight, or on towering Panekire Bluff, hundreds of metres above the water, or within the luxuriant embrace of the mossy rainforest, one feels the full measure of those words, and those that follow: “Te Urewera is a place of spiritual value, with its own mana and mauri. Te Urewera has an identity in and of itself, inspiring people to commit to its care.”

For more than a century, the people most intimately connected to Waikaremōana were unable to exercise their duty of care. Like much of Aotearoa, the story of Waikaremōana is one of dispossession and cultural makeover. From the first whiff of the lake’s tourism potential in the late 1800s, the Crown stripped the lake from the people and the people from the lake. It set in train one of the longest legal proceedings in the country’s history, over who owned “the lake of rippling waters”, as Waikaremōana is usually translated. (“Lake of thrashing waters” would be more consistent with both the taniwha’s struggle and the lake’s political history.)

Across the 20th century, the interest of successive governments in Waikaremōana consisted of tourism, trout and turbines. The needs of the lake’s traditional owners? Not at all. Māori were a minority interest to be managed, mollified and, if necessary, bought off.

In an especially damning section of its eight-volume Te Urewera report, the Waitangi Tribunal wrote: “What is astonishing, in our view, is that in all the evidence and papers available to the Tribunal, the various Government departments and Ministers never once seemed to consider what would benefit Māori or what was in their best interests. Indeed, they had actively sought to defeat the rights claimed by Māori.”

The particular focus of the government’s self-interest was the title to the lake bed. In 1918, the Native Land Court found that the lake bed was owned by some 270 Tūhoe, Ruapani and Kahungunu individuals. This decision was not to the government’s liking. It was already operating a tourism enterprise on the lake, and planning a power scheme. It would be highly inconvenient not to own the lake bed. So it appealed.

And appealed, and prevaricated, and procrastinated—for 52 years. It was not until 1954 that the Crown accepted Māori ownership, but it then took a further 17 years before Māori were given a lease for the lake and some recompense for its use.

“For all those years,” the tribunal wrote, “Māori had been the declared owners of the lake and the Crown had acted, in the words of claimant counsel, as if ‘possession was nine-tenths of the law and it could proceed in treating the lake as its own’.”

Not surprisingly, half a century of government refusal to honour the owners’ mana and pay for the use of their property had severe economic repercussions, following as it did an era of land confiscation. The deprivation was stark. By 1930, the Waikaremōana people retained just over four per cent of the land they had held 50 years earlier, and those that remained in the district lived in poverty. This is the context, the tribunal pointed out, in which the government’s relentless ‘development’ of the lake needs to be judged.

As well as battling high-level government intransigence over the lake title for half a century, local Māori also had to endure lower-level pettiness in bureaucrats and government employees. One of the issues that brought out a mean streak was trout. Rainbow and brown trout began to be introduced to the lake in 1896. A year earlier, during discussions with lake Māori about releasing ‘English fish’ into their waters, Premier Richard Seddon had said that trout would provide an “additional source of food” for them. He also implied that they would conduct the releases and look after the fishery.

None of that happened. Māori were excluded from taking any role in the fishery, and were regarded as poachers if they took a share of the stock. They were told emphatically that trout were not their fish—despite living in their lake, eating its food and displacing its native species.

For the Waikaremōana people, trout and its licensing regime were the thin end of an expanding wedge. In 1898, the government established an imported-game reserve around Waikaremōana, and in 1903, it prohibited hunting. Traditional Māori hunting, trapping and fishing were coming under increasing government scrutiny and pressure, notes the Waitangi Tribunal. Māori were being squeezed by the Crown in terms of their ability to go about daily food-gathering activities, the heart of their subsistence economy.

“Tourism,” the tribunal noted, “precipitated a direct contest between the Crown and Māori for control.”

By the time of the Native Land Court decision over ownership of the lake bed in 1918, the government’s presumption of dominance had hardened. John Salmond, Solicitor-General at the time, declared it was “out of the question” that Māori should have freehold title to lakes or other freshwater bodies. “Such titles would enable the Natives to exclude the whole European population from all rights of fishing, navigation and other use now enjoyed by them,” he wrote.

One of those ‘other uses’ was about to loom large. Between 1929 and 1948, three hydro stations were commissioned along the course of the Waikaretaheke River, the lake’s outflow. They were something of an engineering feat, involving driving a tunnel through the wall of rock that had damned the lake two millennia ago, adding siphons to supplement the flow, and sealing the porous rock around the intake to prevent leakage.

Unlike at Lake Manapouri, where hydro engineers proposed massive raising of the lake level, at Waikaremōana the plan was to dramatically lower it—up to 15 metres, with possible fluctuations of 10 to 12 metres below that. Fortunately, the engineer-in-chief of the Public Works Department saw trouble ahead and warned in 1931 that such an action would give rise to “grave criticism… by a large section of the public”. In the event, the lake was lowered by only five metres, and is maintained within a three-metre fluctuation zone by the scheme’s current operator, Genesis Energy.

In an ironic twist, it was the lowering of the lake that galvanised the government to resolve the lake ownership issue with Tūhoe and the other traditional owners. Fear—or one might say paranoia—was the motivating factor. Lowering the lake had the effect of turning many hectares of lakebed into lakeshore. Who owned that now-exposed lakebed? Māori. With Salmond’s words no doubt drumming in their ears, government officials perceived that Māori could deny access to the lake waters for public or private purposes. They could prevent the building of visitor facilities and services beside the lake. Worse, they could build their own structures on their newly acquired shoreline asset, an activity that could affect the lake’s scenic appeal. Something had to be done.

The government wanted control, but it didn’t own the lake. The owners refused to sell. The deadlock was finally broken when the government agreed to conduct a commercial valuation of both the exposed and submerged parts of the lakebed, and on the basis of that valuation a lease with perpetual right of renewal was enacted in 1971. And that is the situation that pertains today.

[Chapter Break]

What makes Waikaremōana’s clash with colonial power all the more poignant is knowing that the lake once supported a large Māori community. Te Urewera’s 60-year tenure as a national park has tended to obliterate that reality from the public mind. Yet the lakeshore bristles with named features: bays, headlands, caves, former settlements, each of them attesting to centuries of human occupation, many with a story embedded in the name.

Maahu, the murderous father, is mentioned in several place names in the western Wairau Arm of the lake, which was his home. There is a stream he used as a mirror, a stream where he cut his hair, a rock where he had a storehouse, a bay with rocks that look like human figures, said to be his family, and a headland with many flax bushes, representing his hair.

Some of these places are wāhi tapu. I take care not to stop by the flax bushes on the headland. According to tradition, if a person touches Maahu’s hair they will never leave the inlet, paddling in vain towards open water but never reaching it.But I do stop at some of the kainga sites. They are easy to overlook. At first glance, forest seems to descend seamlessly to the shore. But behind the coastal fringe of trees I find large areas of flat ground which were once gardens and home sites. Homes for hundreds. I imagine their lives: fishing, crop growing, birding in the adjacent forests. I grieve their disappearance. The lake is a place of solitude now. I see no other paddlers during my visit. Aside from ski boats at the campgrounds, the only runabouts I see are water taxis ferrying trampers to and from the Great Walk, and the occasional angler.

One night, I pitch my tent on an island in Whakenepuru Bay, also known as Stump Bay because it has two stumps that were left uncut when, in the 1960s, when the lake was at its lowest level, all the protruding stumps around the lake were sawn off or blown up to prevent them becoming navigation hazards once it was raised again.

I doze to the deep bass honking of black swans, of which the lake has legions, and in the morning watch them glide through the mist, some with cygnets in tow. When they take off en masse, the sound of their wingtips beating the water is like a round of applause.

The water is warm and beckoning, so I snorkel to one of the exposed stumps and follow it down to the lakebed, marvelling at the diversity of aquatic plants: thick carpets of bright-green charophytes; the tall, slender stems of pondweed, each with a handful of coppery leaves at the tip, striving upwards towards the light and the air, where they will flower and set seed; milfoils, with whorls of feathery leaves—so many that the generic name for these plants is Myriophyllum, ‘ten thousand leaves’.

Aquatic snails with pale, semi-translucent shells graze over the various species, and a trout fins through the pondweed stems much as a parore swims through kelp in the sea.

Later, at one of the angler cottages in Waikaremōana Motor Camp (each named for a trout lure—this one is ‘Grey Ghost’), Mary de Winton, a freshwater ecologist at NIWA Hamilton, takes me through a list of more than 30 species of amphibious and fully aquatic plants she and her colleagues have found during surveys they have conducted every five years since 2003.

One heartening finding from the surveys is that the diversity of species has remained relatively stable over that period. Indeed, Waikaremōana is considered an exceptionally healthy lake ecosystem. But the lake’s biosecurity can never be taken for granted—as shown by several incursions of the invasive aquatic weed lagarosiphon, a native of South Africa.

Lagarosiphon was sold widely as an oxygen weed for home aquaria, and is thought to have escaped to the wild by people tipping aquarium water into drains and ponds. Now it is spread primarily by contaminated boat, trailer and fishing gear—the means by which it likely entered Waikaremōana. When it was discovered in Rosie Bay in 1999, it triggered an emergency response. Teams of divers crisscrossed the area where the weed had established itself, carefully removing each plant by hand.

If so much as a fragment remains, the plant can regrow, forming dense beds that smother and displace native species. Its stems grow up to five metres tall, and because it occupies shallow waters from two to six metres deep, it can become a serious nuisance for swimmers, anglers and boaters—not to mention clogging hydro intakes.

Between 2014 and 2017, DOC and NIWA conducted annual surveys of the entire 105 kilometres of shoreline, searching for lagarosiphon. Divers used water scooters or were towed behind boats holding a ski rope to cover the ground. The worst-infested area required the use of suction dredges as well as hand harvesting. More than 5000 individual lagarosiphon colonies were removed.

Lagarosiphon is bad enough, but de Winton worries that an even nastier invasive species, hornwort, could potentially be introduced to the lake by a careless angler or boat owner.

“I would cry if that happened,” she says.

Hornwort, considered New Zealand’s most noxious underwater weed, has already infested more than 30 North Island lakes. It grows deeper and taller than lagarosiphon—as high as a three-storey building—and can form large drifting rafts, smothering and outcompeting all native species.

Although biosecurity is a key motivation for recent survey work, happier discoveries are also made. During the most recent deepwater survey, in 2013, the NIWA team found bryophtyes—the phylum of mosses, liverworts and their allies—living on the underside of some of the drowned forest trunks at depths of 18 metres or more.

De Winton finds the parallel with the terrestrial forest fascinating.

“What we see underwater is a mirror of the forest around the lake,” she says. “The trunks provide substrates that would otherwise be unavailable.”

There are few boulders or reefs in the lake depths, just silty sediment, which is not conducive to settlement for encrusting organisms such as sponges or bryozoans.

Fish also take advantage of the sunken forest. Bullies clear the sediment from patches of trunk and lay their eggs there, guarding them until they hatch. The myriad holes and crevices in the decaying trunks are also fine habitat for kōura, the freshwater crayfish, which lifts its pincers like a crab when a diver comes close.

[Chapter Break]

The lake is low. On the shores, broad swathes of amphibious turf—grasses as close-packed and level as a lawn—are high and dry. Sand berms created by lapping waves have carved off sections of the lake margin, turning them into sun-warmed lagoons.

I assume the low level is due to a dry summer, but am told by Tūhoe’s biodiversity team that Genesis, for its own reasons, has drawn down the lake to the lowest permissible level under its resource consent.

Low lake levels cause ecological problems, and are upsetting for the biodiversity staff. The exposed lakeshore enables new plant growth to occur, which attracts rabbits, and predators in their turn.

“It makes it harder for birds to fend off pests, puts pressure on nature and puts pressure on us, the people trying to bring some kind of balance to Te Urewera’s living system,” team leader Herehere Titoko says.

In Tūhoe eyes, restoring the lake’s ecological balance is part of restoring its mana. The way they see it, they are not managing a resource but maintaining a relationship. They serve Te Urewera as its custodian and its voice.

Tūhoe want manuhiri, the lake’s visitors, to be part of that relationship. It starts when they come to what they think is the visitor centre—an impressive new Tūhoe tribal building near the lakeshore at Aniwaniwa—but find instead they are in a whare wānanga, a place to meet and talk to the tangata whenua, to orient themselves to Te Urewera, the living person, and to Papatūānuku, the mother of all.

This can cause some awkwardness and uncertainty, says Tina Wagner, team leader at the centre.

“People say, ‘This isn’t like a DOC visitor centre,’ and of course they’re right!” Having to take their shoes off at the door is a good indication of that. So, too, is a log burner, comfortable couches and long tables with board games walkers can play while waiting for their shuttle or water taxi.

Wagner is often the person walkers speak to about their plans for either the Great Walk around the lake or the many shorter walks on offer. She doesn’t worry if visitors feel awkward at the start.

“Awkwardness can be good if it helps to reset your thinking,” she says.

Outside the building I see Lance Winitana about to do a pick-up for some trampers. I last saw him in 2013, when he told me that as far as Te Urewera is concerned, “the government has the mana, but Tūhoe has the mauri. But one day the mana will come back and run alongside the mauri as one.”

“Has that day come?” I ask him.

“It’s coming,” he says. “We’ve taken the first step—Te Urewera owns itself. Now we’ve got to learn from it. If we can learn how it has survived all this time, we can help it continue to survive.”

Central to all of this is Te Urewera’s personhood, and the lake’s participation in that. The lake’s name almost foretells this outcome.

Waikaremōana’s full name is Waikaremōana whanaunga kore, Waikaremōana beholden to no one. A lake beholden to no one within Te Urewera, owned by no one.

[Chapter Break]

There is one last place I want to visit, a place of origins. I paddle to the end of the western arm, where a stream tumbles down several waterfalls and into a sheltered inlet. Trout swim languidly away as my kayak glides over golden sand. A swan is incubating an egg on a twiggy nest as big as a car tyre. A raft of paradise ducks and ducklings dabble and peep nearby.

I beach the kayak and follow the stream into the forest, pausing to admire its cascades, then return to the broad sandy reach where stream meets lake and let the significance of the place fill my consciousness.

This is Te Punaataupara, Taupara’s pool, the place where Maahu bade his daughter fetch water, then sought to drown her. I picture a girl, regretting her disobedience, coming here to find her sullen father, only to rekindle his wrath. The terror of his violence, but yet the beauty that came from it: a lake of rippling water.

A burst of bubbles from the sand catches my eye. Then another, and another, and all around Taupara’s pool bubbles are rising and popping, and the mirror surface becomes a pattern of ripples. It feels like history’s gift, this springing up of something invisible from beneath the streambed. This mythic place, the start of it all.