Operation Mercury: The Battle of Crete

Operation Mercury—the invasion of Crete by Nazi Germany—began on May 20, 1941, when gliders and paratroops swooped through the dust and smoke thrown up by Luftwaffe bombs and cannon. On the ground, a mixed British, Dominion and Greek army raised its guns to meet them. Mainstay of the Allied defence, where the conflict was most fierce and its outcome decided, was the 2nd New Zealand Division. Sixty years on, as crowds gathered in remembrance of the many who lost their lives in the savage clash, Mark Bathurst trod the battlefield and listened to those with tales to tell.

“It was all here. All just here in this corner.” Arms outstretched, white hair escaping from beneath his blue baseball cap, Mick Reardon gesticulated and pointed. “They had the precise range. A mortar shell came in and hit the boys lying here, and a helmet sailed out right by me.” He blew through pursed lips and carved an arc through the air with his right hand, index finger twirling.

“I was lying outside the cemetery, just over the wall there.” We strode through the entrance to have a look. “There.”

The ground had been concreted over and a bus shelter erected. There was even a wheelie bin—but he didn’t miss a beat. “I never thought I’d stand here again. A helmet… came sailing right past me…”

On the 60th anniversary of the Battle of Crete, in May 2001, I had joined Mick and other war veterans on the Aegean island for what was billed as the last official remembrance of the conflict. A week-long programme of commemorative activities had reached a climax with separate memorial services in honour of those countries that participated in the fighting: Greece, New Zealand, Australia, Great Britain and Germany.

A month previously I had been at Gallipoli, some 550 km across the Aegean Sea, to mark Anzac Day. The inexorable passing of the years means the fighting there is no longer remembered first-hand, and for insight into the experience of battle one must turn to the written record. In Crete, by comparison, the events of May–June 1941, and the years of Nazi occupation that followed, are the stuff of white-hot memory for the many still alive who experienced them. We aren’t talking history here, but people’s yesterdays.

[chapter-break]

Some historians have labelled the period from the Austrian declaration of war on Serbia in July 1914 to the unconditional surrender of Japan in August 1945 as the Thirty-one Years’ War. In this context, it is not so surprising that British and Dominion troops, 26 years after the landings at Gallipoli, should once again have been engaged in military operations in the Mediterranean. The victors of Versailles had merely scotched the imperialist German snake, not killed it. Now, beneath the swastika flag and more venomous than ever, the old foe was once again bent on European domination and expansion eastwards.

Exasperated at the botched invasion of Greece during the winter of 1940– 41 by Italian partner in crime Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler took matters into his own hands. To safeguard the Romanian oil fields at Ploesti and strengthen his southern flank prior to launching Operation Barbarossa—the invasion of Soviet Russia—he struck simultaneously at Yugoslavia and Greece from within Axis-aligned Romania and Bulgaria.

Under-strength and under-equipped, the Greek and British forces in his way—including the inexperienced 2 New Zealand Division—were simply no match for the superbly trained invasion force with its heavy armour and overwhelming air support. Over a period of three weeks, they fell back on ports near Athens and on the Peloponnesus, from where ships of the Royal and Merchant Navies carried some 50,000 men to the safety of Crete and Alexandria. Another 14,000 were left behind and taken prisoner as the home of democracy fell under the Nazi yoke.

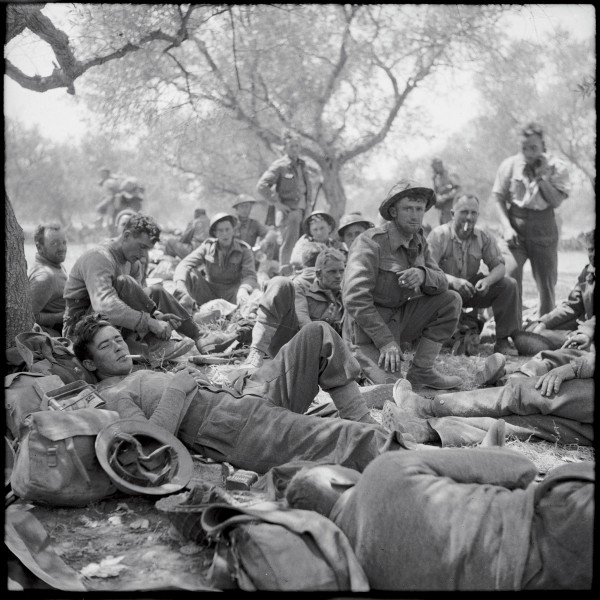

Many of the New Zealanders evacuated to Crete sailed into Souda Bay, a large natural harbour on the north coast, on Anzac Day. Sunken ships victims of Italian torpedo bombers and German Stukas—littered the inlet. Exhausted, the men set up camp among the olive groves behind the derelict waterfront village of Souda and the neighbouring Venetian city of Hania.

Some soon continued on their way to Alexandria, while the rest believed they were to follow in short order. But on April 30, General Sir Archibald Wavell, Middle East Commanderin-Chief, informed New Zealand divisional commander Major-General Bernard Freyberg that a German attack on Crete was expected in a matter of days. Freyberg was duly appointed General Officer Commanding Creforce. The defence of the island was to be his.

The strategic value of Crete had been apparent to both British and Axis military planners since the year before. As an air base the island could be used by the British to probe the Balkans and to threaten Ploesti in particular and by the Axis to strike at Egypt and the Suez Canal and to harass the Royal Navy, the dominant sea power in the region. As a naval base, it offered the largest natural harbour in the Eastern Mediterranean, although one as yet with only minimal port facilities.

During the early stages of Greece’s successful campaign against the Italian invasion, Britain had undertaken to garrison Crete for the Greeks. The Cretan 5th Division, persuaded their home was safe in British hands, had joined the fighting on the mainland. Unfortunately, Wavell had spared little more than a token infantry force to replace them. A Royal Marine formation equipped with some anti-aircraft batteries had since settled in at Souda Bay, while a skeleton air force and a paltry assortment of substandard field guns and light tanks had also found their way to the island. Fortress Crete, however, it was not.

Nor were resources any more forthcoming now the Greek campaign was over. Vast quantities of aircraft, heavy weaponry, transport vehicles, communication equipment and stores had been lost or abandoned in flight and could not be readily replaced, particularly as Wavell had other pressing troubles in North Africa and elsewhere.

German plans for an attack on Crete had been taking shape since early April. Given the strength of the Royal Navy, these revolved around an assault from the air rather than an amphibious landing. Hitler was at once excited by and sceptical of such innovation. General Kurt Student—a passionate believer in the strategic use of paratroops and gliders—overcame the Führer’s doubts, on the understanding that preparations for Barbarossa would not be compromised and that, as insurance against disaster, the air offensive would be reinforced and provisioned by sea. Thus Operation Mercury swung into action.

The British had sound intelligence of the German plan of attack as it developed, thanks to their code-breaking and decryption facility at Bletchley Park. Here, cryptanalysts were able to decipher German radio traffic and thus reveal the enemy’s intentions. This most secret source of military information was known as Ultra. So valuable was it that field commanders—Freyberg included—were kept in the dark as to its true nature. They were instructed merely to accept Ultra intelligence as absolutely reliable, while rumours of highly placed spies were circulated as a screen.

Freyberg’s dispositions in response to the German plan of attack, and his actions during the ensuing battle, have drawn criticism from some commentators, who believe he placed too great an emphasis on the threat from the sea. Others have argued that, while clearly fearful a combined air and sea attack would prove too much given the limited resources at his disposal, Freyberg was perfectly aware of the secondary importance only of watching the beaches and the primary importance of defending Student’s principal targets—the airfields at Maleme, Rethimno and Iraklio (see map).

What is generally agreed, however, is that a number of Freyberg’s field commanders proved insufficiently sharp-witted once battle was joined, with undue concern about the possibility of a major sea attack playing a part in their deliberations. The consequences of their failings were grave indeed.

[chapter-break]

Early one balmy evening, along the coast west of Hania, I walked uphill past shrubs and flowerbeds.

Rounding the last turn in the path, I paused, momentarily entranced.

The hillside above was a carpet of red, mantled in a dense ground cover in full bloom. Immediately before me, a tall cross, painted field grey, rose in austere benediction. Bathed in the ruddy light of the setting sun, the place appeared suffused with blood. Beauty and peace were imbued with a sense of Wagnerian drama.

[sidebar-1]

The Deutscher Soldatenfriedhof, or German war cemetery, is the final place of remembrance for some four‑and-a-half thousand dead.

Set flat into the crimson pile were rows of gravestones. Occasional trios of squat pale crosses protruded, while here and there a bouquet of flowers—a startling upright splash of purple, yellow or cream—bore witness to a life remembered.

The view from this vermilion field of rest—of sea and mountains, of towns and villages now twinkling with lights—was not unworthy of eternal contemplation. Especially so for those remembered there. A short distance below, between road and beach, was an airfield—Maleme. Beside its western perimeter ran a stony-banked river, sunk low—the Tavronitis. The cemetery lay on the side of a hill once known by a number—107.

I was looking at where the Battle of Crete was won and lost.

[chapter-break]

Freyberg set up his headquarters in a hillside quarry just east of Hania. Reading, then meticulously destroying, each piece of Ultra intelligence passed to him, he deployed his forces to counter the approaching invasion. The New Zealand Division covered the Maleme–Hania sector, the four battalions of 5 NZ Brigade, under Brigadier James Hargest, being given the all-important job of defending Maleme airfield. Having no entrenching tools, the men dug slit trenches and latrines with bayonets and helmets, and fashioned sights for their dilapidated field artillery from scrap.

Regular strafing and bombing attacks by the Luftwaffe, known as the daily hate, sent everyone diving for cover—not only to save their lives, but to avoid giving away their positions. Concealment was vital to ensure surprise. In the coming battle, to begin with at least, there would be no front to speak of. The enemy would fall from the sky across a wide area, so attackers and defenders would be instantly intermingled. Defence, therefore, would entail instant attack—pouncing on the enemy where he landed before he had time to secure a lodgement, and mobilising reserves to break up concentrations wherever they started to form.

Initiative would be required at all levels of command—platoon and company as well as battalion and brigade. No help could be expected from the air, the RAF’s few remaining planes having been withdrawn.

On the morning of May 20, through the dust and smoke thrown up around Maleme by the daily hate, fleets of gliders swished eerily earthwards, drawing a hail of small-arms fire from the ground. Some were shot down; others crash-landed and broke apart. Casualties were heavy.

Moments later, the air throbbing to the drone of heavy engines, a seemingly endless procession of Junkers 52 transports lumbered low over the island, haemorrhaging streams of black that separated into trails of canopied V-shapes. A racket of Bren gun and rifle fire swelled beneath the helplessly dangling paratroopers. For many disgorged over concealed positions, this was their last jump. Some finished their descent as corpses, others were dispatched on the ground before they were able to struggle free of their harness. Yet more were cut down as they tried to reach the heavy-weapons canisters dropped with them. A few fell in the sea and drowned. Parachutes hung like shrouds from olive trees, telegraph poles and the roofs of buildings.

Not only New Zealand soldiers, but Cretan civilians—men, women and children, armed with ancient guns, knives and spades—stalked the scattered and momentarily vulnerable Germans. But the turkey shoot was short-lived. The survivors were soon giving a deadly account of themselves as they formed into units.

Most immediately threatening were those of the Assault Regiment, Student’s largest formation, who came down on undefended ground west of the Tavronitis River. They soon launched a determined assault on Maleme airfield and the positions overlooking it on Hill 107, held by 22 Battalion, and seized an RAF camp in the centre of the New Zealand perimeter.

Hamstrung by hopelessly inadequate communications, battalion commander Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew was unable properly to assess the state of battle where the fighting was most fierce. The pressure was clearly mounting, however; hence, also, the need for rapid counter-attack. Yet despite increasingly urgent requests for help, he was unable to convince a curiously indifferent Hargest, at Brigade HQ, or the reserve commanders themselves, to send help.

In growing desperation, Andrew committed his own meagre reserve—a pair of Matilda tanks and an infantry platoon—but the tanks failed and the men were beaten back. Andrew now informed Hargest of his intention to withdraw. “If you must, you must,” came the disconcerting reply, shortly followed by a belated undertaking to send two companies of reinforcements. Andrew stood firm until nightfall, but with still no sign of the promised support he finally took the fateful decision to withdraw his men. By the time the reinforcements arrived, both airfield and Hill 107 had been abandoned.

That the Germans didn’t move in immediately was ironic. Andrew had pulled back fearful that his forward-most units, with which he’d lost contact, had been wiped out, and that without support his remaining forces would be decimated when the Luftwaffe returned in the morning. In fact, along the western edge of the airfield and the Tavronitis side of Hill 107, men were still grimly hanging on. The order to pull back never reached them.

For their part, the Germans feared the battle was all but lost. Reconnaissance had failed to spot most of the camouflaged positions on the ground, so their descent, into unexpectedly fierce opposition, had been highly disorienting, and they had failed to reach a single one of their objectives. Their appalling losses—come nightfall they had just 57 fighting fit facing the airfield—included most platoon, company and battalion commanders. The survivors awaited the expected counter-attack with trepidation.

Both battle commanders, too, were deceived as to the true state of affairs. At his headquarters in Athens, Student came under enormous pressure to abort what was considered to have been a disastrous operation. Maleme was as good as it got. In Agia Valley, south-west of Hania, 3 Regiment had secured another foothold but been forced onto the defensive. The attacks on Rethimno and Iraklio, meanwhile, which had been carried out in the afternoon, had failed to seize either town or airfield, and the outlook for the following day was bleak.

As for Freyberg, while his 10 p.m. signal to Cairo revealed his concern at the “bare” margin by which his forces were holding out, he was clearly encouraged they had “killed large numbers of Germans” and captured an enemy operation order “with most ambitious objectives, all of which failed”. He was as yet unaware of Andrew’s withdrawal.

It was not yet midnight when Captain Campbell, commanding D Company 22 Battalion on Hill 107, suddenly discovered he and his men were alone. He soon decided he had little choice but to pull out too. In an assault on the hill during the small hours, German units clashed only with each other. Despite the mix-up, the vital high ground was secured and Student saw his chance.

Enter Captain Kleye. An intrepid aviator, he accepted the daring mission Student asked of him: to attempt to land at Maleme to ascertain if defenders were still in position along the airfield’s western perimeter. As he was setting off, Captain Johnson’s C Company, shocked to discover that the rest of 22 Battalion had vanished into the night and Hill 107 was in enemy hands, was vacating the very place. When Kleye carried out his test landing, in the first light of day, he was fired on by light artillery some distance east of the airfield, but the western edge was out of range.

The door stood ajar. Student threw in his paratroop reserves and ordered his ground troops onto immediate stand-by.

[chapter-break]

So much is a matter of historical record. But what of those who were there?

Johann Stadler, a retired dentist staying at a hotel near Maleme with other German veterans, was emphatic when I sat with him and his wife among tables and sun loungers near the swimming pool.

“I was very proud. It was the first time in war history an island was conquered from the air.”

A private in the Assault Regiment, Johann was a mere 20 years old when he flung himself in the crucifix position from his Junkers transport above the Tavronitis bridge in the first wave of attack.

“Were you frightened?” I asked. “No.” He was almost vehement. “If you were frightened, you left, you weren’t wanted. We must be prepared to die.” He grinned like a schoolboy who’d just made the first XV, and pronounced, “We were die Speerspitze der Wehrmacht.” The point of the Wehrmacht spear.

What did he recall of the jump?

“My neighbour was killed.” He was referring to a mate who jumped with him—one of the many who didn’t make it to the ground alive. “I saw his grave yesterday.”

He paused, then went on to explain how he came down “near two or three others only”. Armed with just pistols and hand grenades on leaving the plane, they retrieved mortars from the canisters ejected with them and gathered to the west of the river with others who had made it safely to earth. Their orders, he said, were impossible: to “conquer the aerodrome in two hours”. Nevertheless, in response to my asking how he felt at this stage, he was again unambiguous.

“I was excited to fight.”

And fight he did, in the ferocious struggle for the airfield.

In charge of the men he faced was someone equally enthusiastic for the fray. I had spoken to Stan Johnson, captain in charge of C Company, by phone in Auckland several months earlier. He, too, was “proud of what we achieved”. His men had stolen the guns from the wings of some aircraft at Maleme under cover of night.

“So we had plenty of weapons and ammunition, contrary to what you sometimes hear. We had the wing guns rigged up on stands around the airfield, and loads and loads of ammunition. That was how such a small number of New Zealanders killed so many Germans. We couldn’t have done that with just our pistols. We weren’t that strong compared with what the Germans had during the withdrawal from Greece—they were powerful at that time. But we gave a good account of ourselves. We didn’t consider we’d had a loss. Maleme was really a wonderful show.”

I couldn’t get Johann’s “neighbour” out of my head—or the person below who drew a bead on him and squeezed the trigger. One evening I shared a drink with Stan Hadfield in the hotel bar. He described how, stationed east of Maleme with the New Zealand Engineers Detachment, improvising as infantry, he watched as the air above “filled with planes and parachutes like sitting ducks”.

“Did you shoot at them?”

“Yes.”

“What weapon did you have?”

“A rifle.”

“What was it like?”

There was a tremor in his voice. “I was a bit bloody nervous. I’d lost a dixie of porridge.” He grinned weakly. “It was the first time for us close up to the enemy. In Greece we were pulling back blowing up bridges and so forth.”

“Do you remember the fighting?” His ruddy face clouded. “I don’t like to think about it,” he said, and looked down at his glass.

A few months earlier, at his home in Ellerslie, I’d sat with “Fwo” Jones (the acronym, pronounced “Foe”, consists of his initials) as he related his experiences in Crete and, subsequently, a PoW camp in Silesia. A lieutenant, he too was with the Engineers Detachment, and Freyberg had asked him what he thought they could do to protect the airfield without destroying Fwo’s response was classic Kiwi ingenuity.

“I suggested we get all the fencing wire we could and string it across the runway, tightly, so planes coming in to land with troops wouldn’t be able to see it and would tip up. It was the kind of thing our boys could have done overnight almost. It would keep the aerodrome usable for if the RAF came back.

“But Freyberg thought that these wires across the runway would neutralise the thing and nobody would be able to use it. My point was that with a pair of wire-cutters, you cut it and it goes back into its coil, all the way back to one side.”

In the end, the airfield itself was left untouched. This might not have mattered if the area beyond the Tavronitis hadn’t been left unmanned, so handing the Germans a convenient rallying point.

One popular explanation for this startling omission is that by placing troops there Freyberg feared he would betray Ultra.

But then what was intelligence for? Presumably the purpose of informing him of the Germans’ intention to come down there was to let him know the place needed defending, just like the other drop zones. Why make an exception, particularly so close to a prime target?

In fact Freyberg and his replacement as divisional commander, Brigadier Edward Puttick, did discuss the possibility of moving a Greek regiment from Kastelli, about 25 km further west, to the area. But by then time was tight—the German attack was known to be close—and tools were in short supply, and the two men apparently decided it was too late for the Greeks to move and dig in. It is still reasonable to ask why the matter wasn’t given earlier consideration, however. Fwo was not alone in having reached a depressing conclusion.

“From the first time I met the brigadier [Hargest] who was in charge of that area [i.e. the Maleme sector] he was thinking more of retreat, frankly, than he was of attack. It became apparent that the whole tactics and strategy was east of the airport. And this is what destroyed our chances. We could have held Crete, no doubt. But there was undue emphasis on the land [i.e. seaborne] attack.”

Here, then, from an “ordinary” soldier on the spot, was the question that has vexed historians: did Freyberg commit insufficient forces to the defence of Maleme for fear of diminishing his reserves, held back in case of a sea landing further east? Fwo was reluctant to blame the general directly. As to Hargest, on the other hand, his words struck a chord with most accounts of the battle.

Kelly Forest-Brown, patron of the Crete Veterans’ Association, had been even more outspoken the morning we sat over coffee and muffins at his Remuera home. A lieutenant with 18 Battalion, Kelly was posted to 8 Greek Regiment in Agia Valley, commonly referred to as Prison Valley because of a jail block there. On the morning of May 21, he was taken prisoner for several hours, but bolted when his German captors were set upon by a party of “Greek farmers firing blunderbusses”.

Concerning Freyberg: “I think his general plan for the defence of the island was first class, except for this one fault: he put nobody on the west side of the aerodrome.”

And Hargest? Kelly switched from simmer to boil. “He was too old. He was five miles from the front line with his headquarters.”

Kelly singled out another figure also widely criticised for his inaction at the critical moment: Colonel Leckie, commander of 23 Battalion, the reserve force Andrews was expecting to come to his aid.

“His performance was awful. Just lay in the bottom of a slit trench, didn’t give any orders, didn’t counter-attack, didn’t do a darn thing.

“Most of the COs were returned servicemen from World War I, or in their late forties,” he went on. “They didn’t react quickly enough. They all had this phobia of World War I, dig in and defend, whereas the action against paratroopers is to attack the moment they’re dropping, and from there on you never let up, you keep counterattacking until you’ve wiped them all out.”

Whether a symptom of age or not, the motivation of Hargest and Leckie in failing to act when it was imperative they do so has never been satisfactorily explained. Whatever Freyberg’s thoughts on the matter, did Hargest think it more important to retain his reserves in case of attack from the sea? If so, he plainly hadn’t grasped the overriding importance of denying the enemy a foothold close to his primary target—the airfield. Was Leckie’s battalion itself heavily engaged? Not according to its own radio communication with Brigade HQ. Was the situation not clear to Hargest, given the fitful nature of communication and the general confusion of battle? If so, why didn’t he come forward and assess matters for himself?

As an MP, albeit for the National Party, Hargest had the ear of Labour Prime Minister Peter Fraser. He was thus able to put a favourable spin on his actions come the battle post-mortem. The true explanation of his behaviour died with him in 1944.

[chapter-break]

From their new front line a short distance east of Maleme, Hargest and his battalion commanders made no attempt to counter-attack during the daylight hours of May 21. With Puttick’s approval, they decided instead on a night operation to avoid air attack. The survivors of 22 Battalion were split up and reassigned to 21 and 23 Battalions, which were to be bolstered by 20 and 28 (Maori) Battalions. Three light tanks of 3 Hussars and some Australian artillery were to add some clout.

The Germans, meanwhile, were energetically preparing for a fresh offensive. In the morning, paratroop reserves were dropped safely to the west of the Tavronitis. In the afternoon, bombing and strafing by the Luftwaffe paved the way for a ground attack from Maleme and the simultaneous dropping of yet more paratroops. Curiously, these came down over New Zealand positions, and hence met the same fate as so many of their hapless comrades the day before. Only a third survived to slip westwards after dusk.

The ground attack was repelled, too, but the airfield remained in German hands, and late in the afternoon the first in what was soon a steady train of troop-carriers touched down. New Zealand artillery opened up, hitting some planes and causing others to crash, but could not stem the influx of Bavarian and Austrian alpine troops. The Germans fired back with the airfield’s Bofors batteries and worked furiously to clear wreckage from the runway. Prisoners from the day before were forced at gunpoint to fill in craters, some apparently being shot out of hand.

Meanwhile, the first of two German flotillas had set to sea—a not very imposing assemblage of unarmed motorised sailing vessels packed with troops, a couple of rusty steamers, and Lupo, an Italian light destroyer. It was meant to arrive off Hania before nightfall, the Luftwaffe in attendance in case the Royal Navy put in an appearance. But with adverse wind, progress was slow. Night fell, the Luftwaffe withdrew, and the Royal Navy steamed into the Aegean from its daytime retreat west of Crete. Picked up by a formation of destroyers and cruisers, Lupo and its charges didn’t stand a chance. Caught in the glare of searchlights, they were blown out of the water, the gun flashes and glow of burning vessels visible from Creforce HQ.

Back on land, preparations for the counter-attack to retake Maleme were falling behind schedule. Orders were that a start couldn’t be made until an Australian battalion, held in reserve at Georgioupoli, some 40 km east of Hania, had relieved 20 Battalion, on stand-by to repel the threatened sea landing. The Australians were delayed by air strikes; as a result, it was almost dawn on May 22 before the advance began.

Moving west on two fronts—one along the coastal strip either side of the main road, supported by the tanks, the other further inland behind Hill 107 the New Zealanders soon ran into ferocious resistance. In fact, they had foiled a full-scale German offensive. Prominent in the fray was Lieutenant Charles Upham, who mounted a series of destructive attacks on German machine-gun posts and rallied his men to carry wounded from the battlefield actions that would count towards the first of two Victoria Crosses. But daylight brought the Luftwaffe sweeping out of the sky once again, while more transports descended on the cluttered runway, troops plunging from the taxiing planes into the thick of battle. Casualties were heavy on both sides, but it was the New Zealanders who were forced to give ground still short of their objectives.

While the land battle raged, the Royal Navy was having a far messier time dealing with the second flotilla than with the first. Several motorised sailboats were destroyed and the remainder scared off, but German fighters and bombers inflicted grievous harm. Three British ships sank and many others only escaped severely damaged. Hundreds of men drowned or were machine-gunned and bombed while in the water.

[chapter-break]

In prison valley, on the first day of battle, the paratroopers of 3 Regiment had occupied the jail block. Thus provided with a secure base, they had launched several probing attacks at the New Zealanders and Greeks of 10 NZ Brigade in the hills around them. The brigade was a scratch formation, a large part of it the so-called Composite Battalion consisting of service personnel and gunners serving as infantry. Colonel Howard Kippenberger, commanding, had wanted to counter-attack with 20 Battalion, the Divisional Reserve. Also champing at the bit, Brigadier Lindsay Inglis had wanted to deploy the whole of his 4 NZ Brigade, released from its role as Force Reserve to beef up the defence in the area, for the same purpose. Puttick, however, had refused both requests. He, like Hargest, appears to have had more than one eye trained out to sea. Reserves were to be held in reserve. In the end, a quite inadequate force had been dispatched, and the attempt had petered out in confusion in the dark.

The two sides spent May 21 exchanging only intermittent fire. Too weak to launch a major attack, the Germans feared they would themselves be overrun, but the only New Zealand push—by 19 Battalion—was on a forward position on Cemetery Hill, outside the village of Galatos. The defenders were driven off, but German machine-gun and mortar fire from the valley rendered the place uninhabitable—as Mick Reardon’s vivid memory of the flying helmet would never cease to remind him.

Emboldened by the relative quiet, German patrols prowled northwards the following morning while the fight to retake Maleme was at its height, threatening 5 Brigade’s rear. In turn, Kippenberger sent 19 Battalion forward into Prison Valley, but it was forced to withdraw. That evening, a paratroop battalion pressed dangerously towards Galatos, forcing back the New Zealand Petrol Company—a collection of mechanics, drivers and technicians.

Deliverance arrived in an unusual form. A rabble of villagers, including women and children, burst noisily from a nearby olive grove. In front, waving a revolver and blasting instructions on a whistle, ran the dashing fair-haired figure of Michael Forrester, an English captain who was to gain almost mythical status as a leader of Cretan irregulars. As a lesson in the effectiveness of spirited counter-attack this escapade was unequalled. The paratroopers turned and fled. What greater reverses might have been inflicted on the enemy had Puttick given Kippenberger and Inglis a free rein?

As it was, the tide was flowing ever stronger in the Germans’ favour. Plans for a further attempt on Maleme by 5 Brigade were cancelled, and early in the morning of May 23 all troops in the area were ordered back to a line west of Platanias. A further retreat was soon under way to behind 10 and 4 Brigades’ Galatos positions. But for the stubborn resistance of Cretan irregulars and 8 Greek Regiment in the southern reaches of Prison Valley, in no mood to yield before a German right swing, it is likely the New Zealand Division would have been encircled and forced to surrender.

It was the beginning of what was soon to be a rout. But not before an action that is remembered as one of New Zealand’s finest and fiercest.

[chapter-break]

Today, all over Crete, Kiwis are assured of a warm welcome from a grateful people. If this outpouring of generosity has a wellspring, it is in Galatos, synonymous with New Zealand’s wartime help on account of events that took place there on May 25, 1941. Every year, in its little hilltop square overlooked by a twin-towered white church and a couple of tavernas, the village stages the New Zealand service of remembrance in honour of those who gave their lives in defence of the island.

Attendance on the 60th anniversary was impressive. Busloads of war veterans sporting poppies, decorations and regimental colours; dignitaries and uniformed soldiers from the Allied nations; a local guard of honour with military band; nomarchs and priests in the black gowns and pillbox headdress of the Greek Orthodox Church; New Zealand tourists and well-wishers; press and TV crews; the villagers themselves, content to take a back seat as their home became the centre of a nation’s attention—all crowded in as the evening shadows crept across the square, strung with Greek flags.

In the early twilight, a familiar bawling and grunting penetrated the burble of voices. Prancing as if on hot coals one moment, striking defiant poses with raised taiaha the next, a moko’d and piupiu-clad warrior party led Prime Minister Helen Clark and her husband towards the small cenotaph. With all assembled, dirge-like plainchant and solemn recitations from the priests preceded the ritual laying of a mound of wreaths and the planting of a pohutukawa by the PM.

The formalities complete and VIPs escorted from the square, the crowd dispersed in high spirits—mostly in the direction of the aptly named Panorama Hotel, back on the coast road. When I arrived, celebrations were in full swing, attendance threatening to overwhelm the outside dining area as ever more people claiming New Zealand credentials presented themselves at the door and were unhesitatingly ushered in.

At lunch time the following day, after the Greek remembrance service on nearby Cemetery Hill—occasion for a passionate declamation of each Ally’s death tally, punctuated by volleys of automatic gunfire—I returned to Galatos. In the siesta quiet of the square, I observed as a group of three men unobtrusively laid a wreath to one side of the previous evening’s heaped tribute and bowed their heads.

Germans.

[chapter-break]

On the afternoon of May 24, the Luftwaffe, as it had Guernica during the Spanish civil war, carpet-bombed Hania. Only the useful harbour area—today a magnet for tourists—was left untouched. The same fate was visited on Iraklio the following day. Here, the predominantly British defence—and at Rethimno the combined Australian and Greek defence had counter-attacked to great effect and contained the German threat on the ground. The surrounding villages took in the fleeing city populations, while guerrillas and armed civilians roamed the countryside outside Rethimno and Iraklio killing isolated groups of paratroopers wherever they found them.

On May 25, the New Zealand positions in front of Galatos came under immense pressure from mortar fire, strafing Messerschmitts and dive-bombing Stukas. In striking contrast to Hargest, Kippenberger went forward to observe the battle. While he was there, men began to retreat towards the village in disorder, and the line threatened to unravel.

Kippenberger strode among the rabble, grabbing at those closest and bellowing, “Stand for New Zealand!” but to no avail. Reinforcements—among them the band of 4 Brigade and the Kiwi Concert Party—were scraped together and hurried forward to a line between Galatos and the sea, but by early evening the village itself had been conceded.

Determined not to abandon units still holding out round the south-west corner of Galatos, and convinced of the urgent need to hit the enemy hard to prevent the total collapse of his front, Kippenberger decided on immediate counter-attack. Out of the gathering dusk, a couple of 3 Hussars light tanks rolled up under Lieutenant Roy Farran, mustard-keen to lend a hand. Returning from a recce as far as the village square, involving a brisk exchange of fire, Farran reported the place “stiff with Jerries” and undertook to lead the charge.

At Kippenberger’s order, two companies of 23 Battalion, newly arrived outside the village from the rear, fixed bayonets. The crew of his second vehicle having been injured, Farran took a couple of volunteers off for a quick lesson in basic tank operation. Meanwhile, another of the battle’s characters materialised out of the gloom—the blond-headed Captain Forrester. As if on cue, others also began to appear—men who, only shortly before, had been hurrying or limping away. As the numbers swelled, so an infectious sense of exuberant determination took hold.

The improvised assault force formed up on either side of the lane. The tanks returned, halted briefly while last-minute words were exchanged, then ground forward. A group of Maori broke into a haka. Others in the line promptly took up the call. Soon the entire formation was bellowing its pack ferocity. The men swarmed up the lane in the wake of the clattering armour, elements of 18 Battalion in spontaneous support on the left.

Farran’s tank careered into the square, spraying bullets. An anti-tank grenade knocked it out. The crew scrambled free. Lobbing grenades through windows, kicking open doors, firing point blank and driving with their bayonets, the New Zealand soldiers rampaged through the narrow streets. As they spilled into the square, Farran, badly wounded, yelled encouragement from the sheltered side of his tank. Automatic fire from the houses opposite threatened to stem the flow. A hastily organised frontal charge panicked most of the German defenders, who fled in disarray. Others stood firm, turning stampede into mauling retreat, but by midnight Galatos was back in New Zealand hands.

Almost immediately, though, German mortar shells from outside the village began to rain down, and the order to withdraw soon followed. Yet the frenetic assault had bought valuable breathing space, enabling the New Zealand line to fall back on the neighbouring village of Daratsos in relatively good order. Directly west of Hania, 5 Brigade took over the northern end of the front, with 4 Brigade and the remnants of 10 Brigade behind. In the centre, blocking Prison Valley behind the city, were two battalions of 19 Australian Brigade. In the foothills of the White Mountains, the poorly armed 2 Greek Regiment held the southern end.

The counter-attack on Galatos has gone down as a spontaneous expression of pent-up frustration at reluctant retreat, lacklustre leadership and impotence in the face of the marauding Luftwaffe. If only Maleme had been contested with similar urgency!

In one of the tavernas at the edge of the village square, I sat with Bill Smith—born and bred in Gore and still living there at the age of 83—as he shared his recollections of the famous occasion. He spoke calmly, his voice rich with a southern burr.

“The carnage was indescribable. It’s just a haze in my mind now except the horror of it. It was a mad rush—just a frenzied rush. I had a rifle and bayonet and a captured German pistol. I suppose I used my rifle but I prefer to forget about it.”

Bill’s demons, however, had finally been exorcised. Three nights previously, the villagers had thrown a party in their square. Anyone who had turned up had been made welcome, served food and wine at long rows of trestle tables, and treated to a performance of traditional Cretan dancing.

“Saturday night helped me forget about the horror of last time I was here,” Bill said; “it was a sort of therapy for me. I’ll now think of Galatos as Saturday night with all the fun—from the heart of the people.”

[chapter-break]

During May 26, having reoccupied Galatos, the Germans renewed their advance. Along the coast road they closed on Hania, while inland they pressed south of the city towards Souda Bay. Hopelessly outgunned, 2 Greek Regiment began to disintegrate; elsewhere, the pressure became intense.

It was clear to Freyberg that his forces were in an untenable situation and that to save even a proportion of them evacuation would have to be arranged without delay. He signalled as much to Wavell and set about organising as orderly a withdrawal as could be managed, although it would be almost another 30 hours before Wavell, having waited in vain for confirmation from the War Office, gave his consent. A last reserve of British troops was to relieve 5 Brigade and, with the two relatively fresh Australian battalions already in place, to hold the line until a commando unit, expected to arrive by ship at Souda Bay, could be deployed to cover a general retreat over the White Mountains to the south coast. From the tiny beach at Hora Sfakion, the Royal Navy would once again ferry to safety such men as it could.

Freyberg also chose this moment to alter his chain of command. This further confused matters when communication with and between his various field headquarters was already severely hampered by a lack of wirelesses and field telephones, with the result that troop movements were disastrously mistimed.

On the night of May 26–7, the reserve advanced as instructed. But, with 2 Greek Regiment now dispersed, the Australians in Prison Valley had been outflanked, and both they and 5 Brigade had already retired to avoid encirclement. As a result, the British found themselves advancing into a void and by next morning had been cut off. Small parties fought their way back east to rejoin the main force, but the majority either perished or were taken prisoner.

While German paratroopers, filthy and unshaven, advanced through the rubble-strewn streets of Hania, the retreating armies fell back on their next line of defence: a sunken track running south near the head of Souda Bay, nicknamed 42nd Street. Meanwhile, the rearguard commando unit—named Layforce after CO Colonel Laycock of the Royal Horse Guards—had landed and began taking up stations.

Despite growing exhaustion and the inevitability of defeat, antipodean spirits were still far from crushed. When a German mountain regiment, having skirted the clash with the British, happened upon the resting New Zealanders and Australians, they were driven back at the point of the bayonet in another savage counterattack, 28 (Maori) Battalion to the fore. Mick Reardon, with his mates from D (Taranaki) Company 19 Battalion, was among those jolted awake by bloodcurdling yells.

“We’d taken our boots off for a spell when some Germans came round and bayoneted some of the Maoris who were lying down. The others were ropable and went berserk—you don’t kill a Maori while he’s lying down and get away with it—and what with the haka and the screaming of the Germans, the place was in uproar.

“By the time we’d got our boots on the Maoris had driven the Germans back at least a hundred yards. A few sniped at us from a bit further back but they fled in panic, throwing everything away. The Maoris returned with their bayonets dripping blood. I reckon they made the Germans timid, which helped us get away. I’ve always said I’d have been a prisoner if they hadn’t done that. I don’t think they even put their boots on.”

More circumspect the Germans may have been, but they kept coming. As 42nd Street was abandoned on the evening of May 27, Creforce Headquarters joined the exodus south. The New Zealand and Australian infantry marched through the night to Stilos. At daybreak, 23 Battalion repelled another mountain regiment in a vicious engagement involving hand-to-hand fighting. When sniper and mortar fire then plagued the continuing withdrawal, Sergeant Clive Hulme infiltrated the German lines and added to an already astounding tally of snipers stalked and shot during the preceding days. For his final count of 33, as well as conspicuous gallantry in pitched battle at Maleme and Galatos, he was subsequently awarded the Victoria Cross.

In a succession of further defensive actions to the rear, Layforce held the enemy in check with Maori and Australian help. Meanwhile the bulk of the Allied army trudged wearily through the foothills towards Vrysses and the looming mountains beyond.

For men already battle-fatigued, footsore, seared by thirst and weak from hunger, the ascent from Vrysses was a gruelling trek. As the unending stream of men and vehicles toiled up the dusty, stony road under a grilling sun, one false crest of glaring shale and limestone heartbreakingly succeeded another. The way became littered with discarded equipment—kitbags and blankets, rifles and cartridge cases. Vehicles that broke down or ran out of petrol were abandoned or tipped into the valley below.

Units that could still form up marched in regular fashion; others proceeded in disorder. The angry roar of a foraying Messerschmitt was the signal to flatten in terror against the stony ground. First to pull back and with few officers to maintain discipline, the unarmed rear echelon of base-area personnel raided such supply dumps as there had been time to lay, leaving the fighting troops following behind to pick over the remains or forage.

Reaching Askifou Plain, a fertile oasis of fields and orchards, weary New Zealand and Australian battalions once again took up defensive positions on the night of May 28–29. Behind a series of rearguard engagements they withdrew across the plain and down Imbros Gorge to the coast, covering the evacuation, over three nights, of many of those ahead of them. Creforce Headquarters was established in a cave below where the road petered out at the top of a precipitous bluff overlooking the sea.

Who was to leave and who to stay? Perhaps inevitably, the several thousand non-fighting men, by now leading a feral existence in the area’s many caves, drew the short straw. Priority was given to walking wounded, officers and combat troops, and only formed-up bodies were allowed to embark. Outside a cordon of fixed bayonets around the embarkation area, the leaderless implored any passing officer to draw them up and so secure them a place. Some resorted to subterfuge, faking wounds or claiming special status. The Maori Battalion took no chances, keeping would-be infiltrators at bay with pointing sub-machine guns. Freyberg himself was airlifted to safety by Sunderland flying boat on the night of May 30.

A few hours before he left, a German detachment penetrated towards the coast down a ravine to the west of Imbros Gorge. Lieutenant Upham, by now both wounded and racked with dysentery, led his platoon round the cliff tops above, from where he and his men poured machine-gun and rifle fire on the intruders. Upham’s first Victoria Cross was in the bag.

At Iraklio, the order to evacuate was received with bitter astonishment. The British garrison nevertheless withdrew in perfect order, to be spirited away by a Royal Navy squadron. The following morning, however, Stuka bombs penetrated below decks and exploded among the packed-in soldiers with devastating effect.

As for the battle group at Rethimno, Freyberg had been unable to make contact. Furthermore, misled by abysmal intelligence, the Germans had thrown the bulk of their army in that direction, only a modest force sheering off towards Hora Sfakion in pursuit of the main retreat. With paratroops now also advancing from Iraklio, there was no escape. Threatened with reprisals against the civilian population if resistance continued, the Australian commanding officer, Colonel Campbell, surrendered.

On the fourth and final night of the navy rescue, May 31–June 1, four fast ships were to lift as many men as could be crowded on board. Anyone left behind was to surrender. At the urging of Prime Minister Peter Fraser, in Alexandria to do all he could for his beleaguered countrymen and to welcome them off the boats, a fifth vessel was added to the evacuation force.

It was the turn of the last of the rearguard. But the Australians of 2/7 Battalion, having held the perimeter to the end, were obstructed on their way down to the beach by others angry at being left behind and were late lining up. The rasping of lifting anchor chains across the water spelt out their fate—bitter reward for their efforts.

Come morning, it fell to their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Theo Walker, to deliver the surrender.

[chapter-break]

Some 5–6000 troops remained at the mercy of the enemy. Hundreds took to the hills to avoid capture. Some of these eventually escaped by submarine or fishing boat; others hid out for years and took part in the resistance. Most were eventually taken prisoner. The majority of those left behind had to face the torturous trek back over the mountains to Hania, the unsanitary conditions of a makeshift prison camp, and eventual shipment to stalags in mainland Europe.

For those fortunate enough to have been rescued, the threat of air attack was the final ordeal. Several ships were hit and many on board killed or wounded, while the anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Calcutta, despatched to cover the last night’s flotilla, was sunk.

Shambling down the gangway in Alexandria, some battalions refused to appear defeated. They fell in on the quayside before marching off in order. For their leaders, the inquest into what had gone wrong loomed.

Hargest furnished Fraser with his deftly glossed version of events, while Inglis, in a verbal report to Churchill in London, criticised both Middle East Command—Wavell’s province—and the handling of the battle—Freyberg’s responsibility. As a result, Freyberg fell under the suspicion of both prime ministers. Unlike Wavell, however—already mistrusted by Churchill—he survived, thanks in part to the testimony of both Wavell himself and Wavell’s eventual replacement, General Sir Claude Auchinleck.

For Student, the taking of Crete was a “disastrous victory”, the island itself “the grave of the German parachutist”. Although every surviving paratrooper was awarded the Iron Cross, losses had been huge and Hitler never again ordered an airborne attack. The psychological impact of Operation Mercury on Britain and America, however, was such that both countries pressed ahead with developing their own airborne capabilities. These would prove their worth in the 1944 invasion of Normandy and the crossing of the Rhine the following year. In between, however, lay failure at Arnhem. In command of the German front on that fateful occasion was none other than General Kurt Student himself.

With Crete roped in to the Nazi laager, Germany’s occupation of Western Europe reached its high-water mark. Hitler now turned east, launching Operation Barbarossa just three weeks later. The consequences for the Third Reich would ultimately prove terminal, while the war in North Africa—in which Freyberg, still in command of 2 NZ Division, did much to recover his reputation—was soon to deliver Germany’s first land defeat. But in June 1941, it took a brave man to gainsay the Führer’s dream of an empire stretching from the Atlantic seaboard to the Urals.

At Iraklio, Rethimno and Galatos, however, a light had gleamed briefly in the dark. In their improvised defence of Crete, the Allies had put up the most spirited resistance to date against Nazi Germany’s relentless march across continental Europe and dealt its army a distinctly bloody nose. Notice had been served that the enemies of fascism, New Zealand prominent among them, would henceforth prove an increasingly formidable foe.