The merchant of Taranaki

In a climate of fanatical anti-Chinese sentiment, Chew Chong saved the bacon of Taranaki pioneer farmers, contributed significantly to New Zealand’s dairy industry, and was acknowledged for it in his lifetime.

“It is popularly reported that quite a lot of cockies of North Taranaki say their prayers to Mr Chew Chong instead of to the great goddess Cow,” claimed the New Zealand Freelance in 1911, and continued with the understatement, “It isn’t often that a Chinaman gets an Illuminated Address.”

For decades, Chinese immigrants to New Zealand got little but public intolerance and discriminatory legalisation. So it was with some pride that the citizens of Taranaki filled New Plymouth’s town hall on a Saturday afternoon in January 1911 to honour Chong, because, as the Taranaki Herald put it, “There are few who have done more for Taranaki than Mr Chew Chong.”

With white hair, walrus moustache, a shuffling gait and always dapper in either a three-piece suit and bowler hat or a tussore silk three-quarter coat and black trousers, Chong accepted the illuminated address from the Mayor of New Plymouth, Gustave Tisch. The ornate calligraphy on the fine calf-skin parchment begins, “We, the undersigned Settlers in the Taranaki District, wish to place on record our appreciation of the services which you have rendered to your adopted country…”

Adopting a country was unusual in itself. The 100,000 Chinese who left the Canton (Guangzhou) area between 1840 and 1876 to try their luck on Californian, Canadian and Australian goldfields were mostly illiterate peasants out to make a quick yuan before returning home. The villages they left were often built on Feng Shui principles: located below lightly wooded hills, fringed by bamboo groves, fronted by a pond, and observing the traditional saying, “To the right an ancestral shrine, to the left a shrine to the earth gods”. Beyond, tracks meandered through rice paddies.

Sounds idyllic—so why leave? The answer can be found in Kaiping, near Canton, where Chong was born. The stone and rammed-earth diaolous, or watchtowers—one-room square structures rising up to five storeys—still add an exotic touch, with architectural features borrowed from Greek, Roman, Gothic, Islamic and Baroque styles. But in the early 19th century their names, like The World Lives in Peace Tower and Peaceful Life Tower, reflected hope rather than reality, for their primary purpose was to protect villagers from marauding bandits. Adding to their troubles were land shortages, famine, drought and floods.

This world of Chong’s deteriorated further with the First Opium War of 1839–42. At its conclusion, the port of Canton lost its 85-year monopoly on foreign trade when China opened another four ports. The region fell into economic depression and endured another three rebellions before the Second Opium War of 1856–60.

Meanwhile, in 1850, the discovery of the world’s richest alluvial goldfields around what is now Castlemaine, in Victoria, Australia, immediately lured thousands of Cantonese—but not Chong. As a young man he moved to Singapore, working as a houseboy and improving his English in an English-speaking household. In 1855, he moved again, to Victoria, but didn’t dig for gold like the other 17,000 Chinese. Instead, he began his lifelong occupation as a merchant, opening a shop in Castlemaine’s Chinatown. While his countrymen shipped 205,464 ounces of gold to Canton from Victoria in 1857, they did so in an environment of ever-increasing alienation.

In the year of his arrival, the state of Victoria imposed a £10 poll tax on Chinese immigrants. Eventually, all Australian colonies followed suit. The intolerance behind this tax also erupted into violence, and it would have been extremely unlikely that Chong avoided its effects. In fact, one of Australia’s most violent episodes happened near Chong’s store on July 4, 1857. A mob of 50 miners, some on horseback and armed with clubs, knives and rifles, raged through 13 km of Buckland Valley, torching tents, destroying and looting camps and bashing, killing and clearing the fields of 2,500 so-called “Celestials” in what came to be known as the Buckland Riots.

Almost a decade later, across the Tasman, thousands of diggers were deserting Otago for the Marlborough and West Coast goldfields. To alleviate the loss, the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce invited the Chinese miners from Victoria, then 40,000 strong, with assurances they would “receive the same protection as other residents receive”. When Chong arrived in 1867 he joined 1185 other Chinese migrants searching for their fortune in Otago.

But while they didn’t experience the mob violence they suffered in Australia, neither were they made welcome—organisations such as the White New Zealand League, the Anti-Chinese Association, the Anti-Chinese League and the Anti-Asiatic League saw to that. And few individuals were more anti-Chinese than another new arrival from Victoria, Richard Seddon, who also took up gold mining and later served as Premier of New Zealand from 1893–1906. In his very first political speech, in 1879, he declared, “I do not think that the Chinese are desirable colonists. I would sooner address white men than these Chinese; you can’t talk to them, you can’t reason with them…they are a hard pill to swallow.”

More than 40 anti-Chinese laws were enacted before Chong’s death in 1920. Among them, his adopted country outlawed Chinese games of chance, excluded Chinese when it reduced and later abolished naturalisation fees, then denied them naturalisation altogether, refused to grant them old-age and widow pensions, required their thumbprints if they temporarily left the country, allowed police to enter their homes without a search warrant, let only “British” New Zealanders decide on retail closing hours, introduced a 100-word English reading test of standard-four level for Chinese immigrants only, and restricted laundry hours to “reduce the advantages enjoyed by Chinese…in competition with Europeans”. But most devastating was the £10 poll tax on Chinese immigrants introduced in 1881 and raised to £100 in 1903.

All this, however, was still in Chong’s future, and in 1867 he set to work buying scrap metal for export to China. Three years later, he moved to New Plymouth and started buying an export product that, for many settlers, saved their hides.

[Chapter Break]

Its smooth and dry surface varies from dark brown to black. The soft, rubbery flesh jiggles slightly. It has no gills or stems and often blooms up to 20 cm wide. It contains carbohydrates, calcium, potassium, iron, the same percentage of protein as meat, including eight kinds of amino acids, and is low in fat. The Chinese used it to lower cholesterol, coagulate and purify blood, improve circulation and aid wellbeing, and as an antiseptic mouthwash, an aphrodisiac and an ingredient in wood glue. But it was mostly used for cooking. Being tasteless, it absorbs the flavours of, usually, soups, stir-fries and stuffings. The Chinese called it mu-er. Maori called it hakekakeka or harori. Taranaki folk coined many names for it: wood ear fungus, edible jelly fungus, Egmont gold, black gold and “Taranaki wool”. Taxonomically, it’s known as Auricularia polytricha. But whatever it’s called, Chong’s illuminated address of 1911 notes that “the export trade in Fungus was the means of saving many a family from want and penury in the early days of settlement in the district”.

Don Drabble, an Eltham historian who spent two and a half years researching Chong, says, “It was almost as if he had come here for that reason.” Chong offered two pence a pound for it in the 1870s and up to 10 pence a pound in the 1890s. He exported fungus throughout his life—from 1872 to 1904 he shipped 8400 tons, paying out £309,343. At the peak of production, the province often earned more from exporting fungus than butter—so it was “Taranaki wool”, not Taranaki butter, that kept farmers on the land.

While Chong was happy to barter goods, he was probably the only storekeeper in the area to consistently pay cash, and the importance of this can’t be overstated. Money was in desperately short supply but needed for non-tradable expenses such as farm mortgage instalments and local rates. Chong’s cash payments helped countless farmers.

Farmers like Richard Price. He landed at New Plymouth in 1876 and walked 16 km with his dog to Egmont Village, only to find his 223 acres smothered with bush so dense he had to fell trees to make enough room for a small ponga whare—never mind pasture for cows. In the meantime, he lived under the roots of a colossal rimu tree, collected fungus and sold it to Chong.

Near Auroa in South Taranaki, Charles Davies took on 106 acres of bush. His cows carried his three children into the bush, then the fungus out, and the children sold it to Chong.

“When Mr Chew Chong first arrived in New Plymouth, it was said that he would be able to obtain but little fungus as it would not pay to gather,” reported the Taranaki Herald in September 1871. “It appears however, that persons were mistaken in their surmise, for as it now turns out, fungus gathering is likely to prove a profitable industry for some time to come. A man can gather from two to five sacks full in a day. The price paid for it is 6 shillings per sack.” At that time, a pound of beef cost two pence, butter eleven pence, and pork five shillings.

As 17 per cent of the fungus is water, it attracted a higher price in its dried form. William Kennedy noted in 1884 that “much ingenuity was displayed in the contrivance of drying it. Frames were made from [supplejack] and put over the fire in the large bush fireplaces…and turned and not allowed to burn. A few sheets of iron would often be arranged outside and…a fire would be kept going under this.” In 1887, the Hawera & Normanby Star reported, “It is now a common thing to see whole families on the road side and in their clearings collecting ‘Taranaki wool’ and making the work half pleasure and whole profit.”

[Chapter Break]

“In the early 1870s there was real excitement,” says one New Plymouth report, “when a new peddler appeared at lonely farms, a little Chinese man complete with pigtail and coolie hat, strange clothes and a singsong voice.” With horse and cart, Chong plodded door to door, selling the usual tea, sugar, flour, tin billies, farmers tools, lanterns, kerosene and a variety of children’s toys from around the world. Rosemary Lyon wrote, “The children regarded him as a magical person because of his exotic appearance and kindly disposition.”

In March 1873, Chong left William Cottier’s Taranaki Hotel in New Plymouth, where he had resided since 1870, to live and trade from his first shop on the corner of Devon and Currie Streets. While an important milestone, it was not as significant as the next.

Before a district court judge, Chong affirmed, “I do sincerely promise and swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Victoria as lawful sovereign…so help me God.” On July 1, 1873, Sir James Fergusson, Governor and Commander-in-Chief of New Zealand, granted “unto the said Chew Chong these letters of naturalisation”. Chong thus became a New Zealander. In 1875, at a time when inter-racial marriage was almost unheard of in New Zealand, he married Elizabeth Whatton. They went on to have 11 children, although five died in childhood.

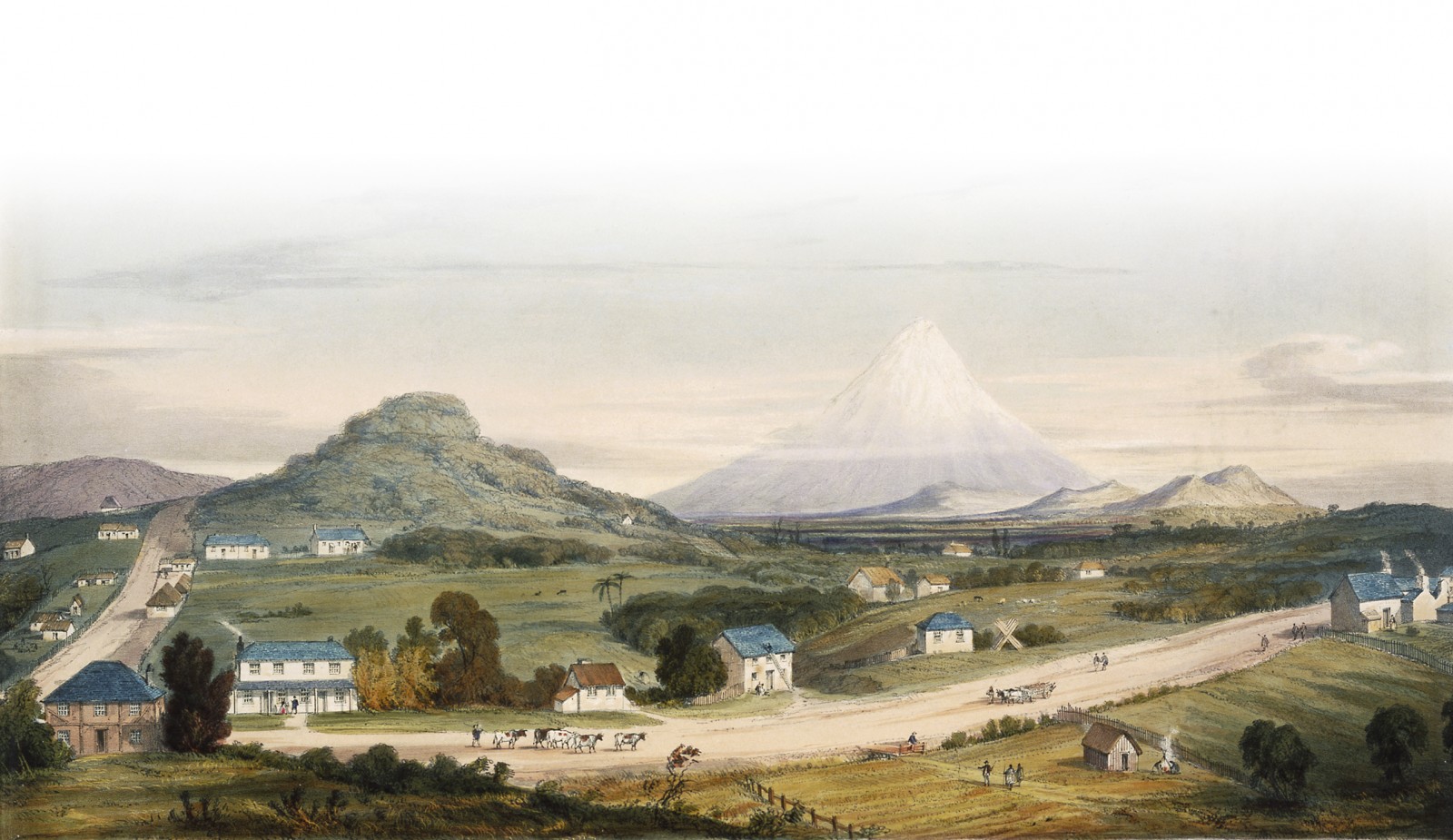

Meanwhile, settlers carried their swags to the province’s first inland settlement, Inglewood, because the boggy road was impassable to bullock drays. The first sections sold in early 1875. In May, Alfred Trimble, an early visitor to Inglewood, described the town as “just an ordinary bush clearing, black and ugly, with a muddy track cutting it from North to South”. But Chong saw its potential, and opened a store there.

From 1878 to 1886, Taranaki grew faster than any other province, and more than twice as fast as the colony, and in 1881 steam trains connected New Plymouth with Hawera. In 1882, when Chong already had stores in New Plymouth, Okato, Inglewood and Hawera, he opened one in the town that would have the greatest impact on his business life—Eltham.

Even before Peter Cheal of the Survey Department finished plotting Eltham, the bushmen arrived. “Axe and saw were plied with vigour and, in a few days, for the first time in thousands of years, the sun’s rays penetrated deep into the undergrowth,” writes Cheal. “Now, also, we got a fine view of the mountain [Egmont/Taranaki] soon to be hidden from sight by the towering peak of a colossal smoke column caused by burning off operations.”

When Chong arrived, a boot repairer was the only other business in town. Chong rented a room as a shop for two years in one of the few cottages that dotted Eltham’s charred landscape, before buying land on the corner of today’s Bridge and Railway Streets. There he built a 12-metre by 11-metre building with “1884–CHEW CHONG” painted above the verandah. By 1891, his Eltham business interests had grown to include a stable, blacksmith, butchery and bakery. In 1900, fire destroyed the first store, and in 1903 its replacement suffered the same fate. But a greater threat to Chong’s enterprises had arrived years earlier in the form of a boy: Charles Anderson Wilkinson.

Wilkinson was four when his parents bought the Urenui Hotel in 1872. On Chong’s regular visits, he bought fungus from the boy. The Wilkinsons sold the hotel in 1877, and the father abandoned the family. The mother took two of her children to Nelson, but left nine-year-old Charles in New Plymouth. Meanwhile, young Wilkinson’s grandfather bequeathed him an investment fund, maturing when he turned 21, and in the interim, an annual income from the fund’s interest for maintenance and education. Various relatives raised the boy until he finished his education and started working on farms north of New Plymouth. When his father heard that a farmer was abusing Charles, including throwing food to him on the floor, he implored his old friend Chew Chong to help.

Chong, in a characteristic act of compassion, employed the teenager in 1884 to manage the Eltham store. Later, when Wilkinson appeared in court on forgery charges for allegedly altering a cheque, Chong defended him by declaring his “unlimited confidence in [Wilkinson’s] honesty”. The case was dismissed, but on turning 21, Wilkinson would become Chong’s fiercest competitor.

[Chapter Break]

At all his stores, Chong bought or bartered butter from local farmers who were, unfortunately, more adept at burning bush than beating butter. As H.G. Philpott observed in A History of the New Zealand Dairy Industry, butter “must have been such that it is doubtful if even the refrigerator would have enabled it to reach the consumer’s table in edible condition”.

Once in store, each batch of butter was mixed with others to make “milled” butter, so the most unpalatable tainted the whole. Chong bought more than he could sell locally, so started exporting, first sending a kauri keg of it to Australia in 1874. He lost money and the feedback was that “your butter is only like cart grease”. Chong encouraged better butter-making practices with a competition, but exports became reliable only with the advent of refrigerated shipping. When the refrigerated Dunedin sailed from Port Chalmers for England on February 15, 1882, with 1200 tons of frozen meat on board, it also carried a little butter, which later met with market approval.

Just two years later, Geo Brown, the Inspector of Dairy Factories, wrote, “We have only to make the prime article in butter and cheese, then no power on earth can stay the flow of gold in this direction”, a statement prescient of the future of the nation.

The dairy industry may have had its genesis in the South Island, but it was in the better, wetter soils of Taranaki, Manawatu and Waikato that it really met with commercial success.

And it was the demure Chinese trader who was responsible for pioneering the industrial production techniques on which the industry is built today.

Chong bought more than an acre of land on the outskirts of Eltham in June 1887 to establish a butter factory, and local farmers, who owned 250 cows between them, guaranteed milk supply at two and a half pence a gallon in summer and three pence in winter, with the option to buy returned skim milk at one penny a gallon, which they fed to their pigs. Chong employed brothers Sydney and Arthur Morris as butter makers, and opened his Jubilee factory—named to commemorate Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee that year—on December 27, 1887.

Within six weeks, the Taranaki Herald judged Jubilee’s butter as “well made, of good flavour, and altogether a superior article and should meet with a ready sale”. Later in 1888, the Government’s dairy inspector, R.M. McCullum, awarded Jubilee the “palm among butter factories”, saying that “this is one of the best factories I have visited…everything about it is thoroughly clean”.

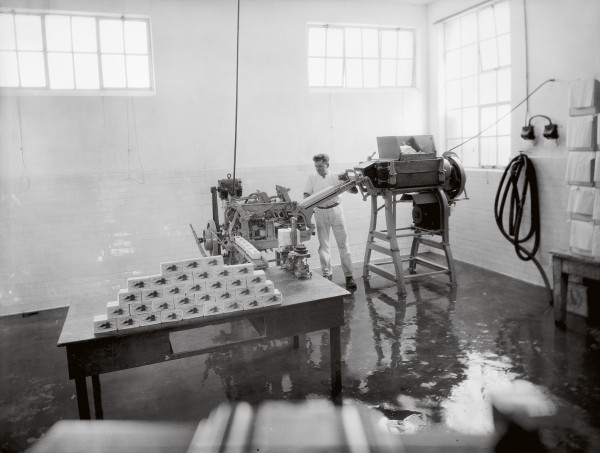

In the same year, Chong is credited with installing the first refrigeration unit in a New Zealand butter factory, almost a decade before refrigeration became widespread. He also helped to pioneer today’s share-milking system, invented a rotary butter worker, an air cooler and an impressed brand for butter boxes which standardised butter into the one pound blocks that we are familiar with today. A 1933 publication, The New Zealand Dairy Industry, claimed Chong was “the originator of the dairy factory system”, and his illuminated address observes: “When later you entered into the butter business being almost a pioneer in factory manufacture you led the way into what has become the mainstay of the district and helped to develop an export which materially assists in the prosperity of the Dominion.”

But even before the Dunedin exhibition, Chong’s nemesis, Charles Wilkinson, had cashed in his inheritance. Within three months of collecting it in July, he had resigned from Chong’s and bought the timber mill store at Ngaere. Four kilometres south, at Eltham, he had a new store built by November. The following year, he bought the Mangatoki Store, about seven kilometres west of Eltham, and built a butter factory costing £2000. By April 1891, he was bankrupt.

A month into his bankruptcy, Wilkinson formed a partnership with George Buckeridge and they addressed the Eltham Farmers Club, urging members to establish a co-operative dairy factory. When they failed to persuade the dairymen, Buckeridge bought a farm and 10 cows—now he, too, was a farmer. Chong felt the pinch and raised the next season’s payout offer to three pence a gallon, a previously unheard of figure, simply to secure supply. However, Wilkinson rallied the farmers, convincing them to leave Chong and form the Eltham Dairy Factory Company.

At the Eltham co-operative’s first annual meeting in 1893, its secretary, J. Ure Murray, delivered a thinly veiled attack on Chong: “The time has nearly gone when settlers are content to drudge from early morning to late night milking cows and paying a tax of one pence on each gallon they milk into some capitalist’s pocket. They are very simple, we think, who beguile themselves with the idea that any person or company will come forward and do everything for them in the way of laying out money on a factory without being allowed a finger in the pie.”

The 1890s saw co-operatives usurping proprietary factories, and by 1900, 110 of New Zealand’s 263 dairy factories were co-ops.

Chong saw the writing on the wall and made an offer to sell the Jubilee factory to the Eltham co-operative, but its members “unanimously resolved that it be not entertained”. As farmers left Chong, he bought 140 cows to shore up supply, but inevitably closed Jubilee in 1901. The factory that had cost him £3700 to build was sold to Wilkinson for £400.

Ultimately, Chong’s foray into the dairy industry cost him £7000 and, as that illuminated address so wryly notes, “That [the dairy-factory system] mostly passed from private into co-operative hands and therefore caused you considerable pecuniary loss is on your account to be deplored but cannot be traced to a want of business acumen, nor a want of desire to assist your fellow settlers on your part.”

One of Chong’s grandsons, Brian Chong, told me, “Chew made loans to the farmers with the shake of a hand, and when the farmers went co-operative he didn’t get his money back. But I don’t think he bore any malice.”

The address concludes, “We wish that we may for many years constantly meet you in our midst and that you may enjoy the rest to which your years and exertions entitle you.”

![102_chewchong_bodyimage7 Chong’s most public achievement came at the New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition in Dunedin. Between November 1889 and April 1890, over 625,000 visitors viewed a range of displays, including a Chinese flag above Chong’s dairy exhibit. Dunedin’s Otago Witness reported, “farmers from all over the colony have taken advantage of it...about 50 exhibitors in the various classes—one of them being a Chinaman, whose boldness in entering the field against his English brethren gained for him first honours for a half-ton of butter [ready for export]”. Today, his winning silver cup is on display at New Plymouth’s Puke Ariki museum.](https://images.nzgeo.com/1970/01/102_chewchong_bodyimage7-362x600.jpg)

Chong retired after closing Jubilee at 73 years old, but maintained financial interests in various businesses. He returned to China for six months in 1905, and in his last years favoured cooking, entertaining children and tending two glasshouses—each bigger than Eltham’s first large store—growing tomatoes, chillies and grapes.

Historian James Ng claims Maori appointed Chong an ahupiri, or regional chief, and 76 years after his death in 1920, Chong was inducted into the Enterprise New Zealand Business Hall of Fame. The New Plymouth press, which had always been generous in its coverage of Chong, commented, “Almost unknown and unrecognised, even in his home region…Chong’s endeavours epitomise the achievements of the early, hard-working Asian arrivals who were too often relegated to second class citizen status…It is good to see who has had the last laugh.”