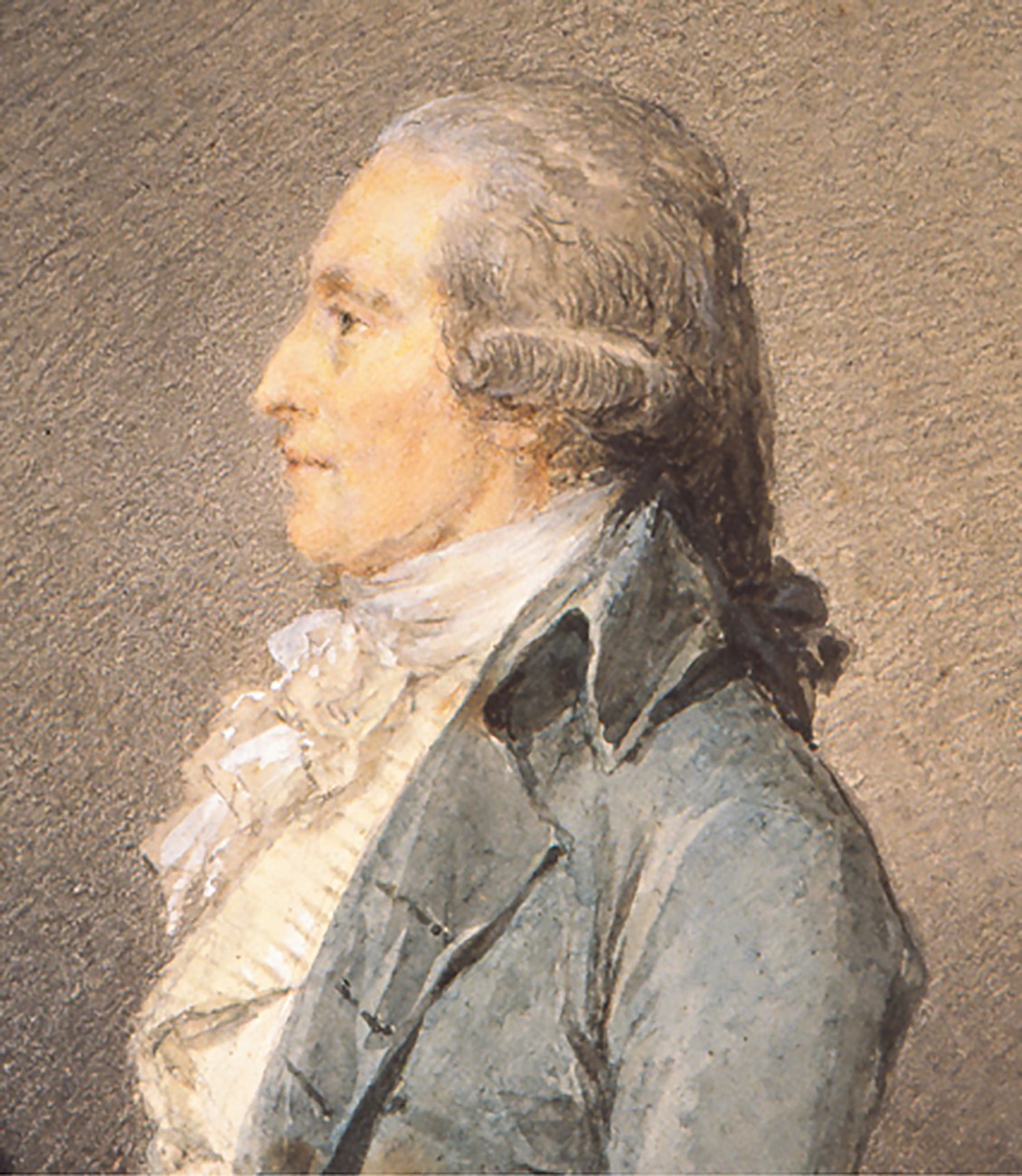

Carl Linnaeus

To mark the 300th anniversary of the birth of Carl Linnaeus, a former student of taxonomy considers the life and legacy of Sweden’s most famous naturalist.

For two years in the late 1970s I followed in the footsteps of Carl Linnaeus: I toiled in the field of taxonomy. The small corner of nature’s jigsaw I tackled was a group of New Zealand marine sponges whose baffling variability defied easy classification. I considered their colour and form, examined their skeletal architecture, counted their spicules, noted the shape of their larvae, and pondered which of these characters could be used to separate my subjects into meaningful categories.

The result of my labours was a classification scheme for 43 species of sponge—an achievement of near insignificance when placed alongside that of Linnaeus, who in the course of his life classified and named more than 4000 animals and nearly 8000 plants. As superhuman a feat as that was, the illustrious Swede also invented the system of classification that every student of taxonomy, myself included, has used since.

The eldest son of a small-town curate and expected to follow that calling, Linnaeus chose instead to pursue his father’s recreational interest in plants and became the greatest botanist of his time. He was also a successful physician (attending Swedish royalty), a charismatic lecturer, a devoted mentor, an enthusiastic gardener and a prolific writer. He not only sorted and systematised all the known species of his day, but also pioneered the study of how indigenous people use plants for medical and other purposes, earning the sobriquet “father of ethnobotany”. The simplicity and logic of his taxonomic system made natural history accessible to amateurs, ushering in the Victorian passion for nature. Jean Jacques Rousseau said of him, “I know no greater man on earth.”

It is as a taxonomist that Linnaeus is chiefly remembered. His genius was to apply the social hierarchy of his time, with its kingdoms, provinces, parishes and villages, to the natural world. He slotted plants and animals into a hierarchy of categories, each nesting like a Russian doll within the next. His sequence—species, genus, order, class, kingdom—is still in use, augmented by a still-expanding bevy of additional gradations, such as subspecies, tribe, family, phylum and, more recently, phalanx, infracohort and supertribe.

Almost incidental to Linnaeus’s encyclopaedic audit of the natural world was his decision to call each living thing by just two Latin names, representing the genus and the species. Yet this innovation, known as binomial nomenclature, has proved to be his greatest gift to posterity. Any time Homo sapiens or Felix domestica—or, in my case, Callyspongia ramosa—is mentioned, Linnaeus’s naming system is invoked.

Before Linnaeus, the naming of organisms was a shambles. There were multiple names for even the commonest species, and as many criteria for classifying them as there were scientists doing the classification. Instead of Linnaeus’s concise, double-barrelled binomials there were wordy polynomials composed of a dozen or more terms—descriptions more than names. The tomato, for example, was Solanum caule inermi herbaceo, foliis pinnatis incises—the solanum with the smooth stem which is herbaceous and has incised pinnate leaves. Out of a Babel of complicated, competing nomenclatures Linnaeus forged a single, universally applicable scientific language. For this he has been likened to Hercules, bringing order to the Augean stables of natural history.

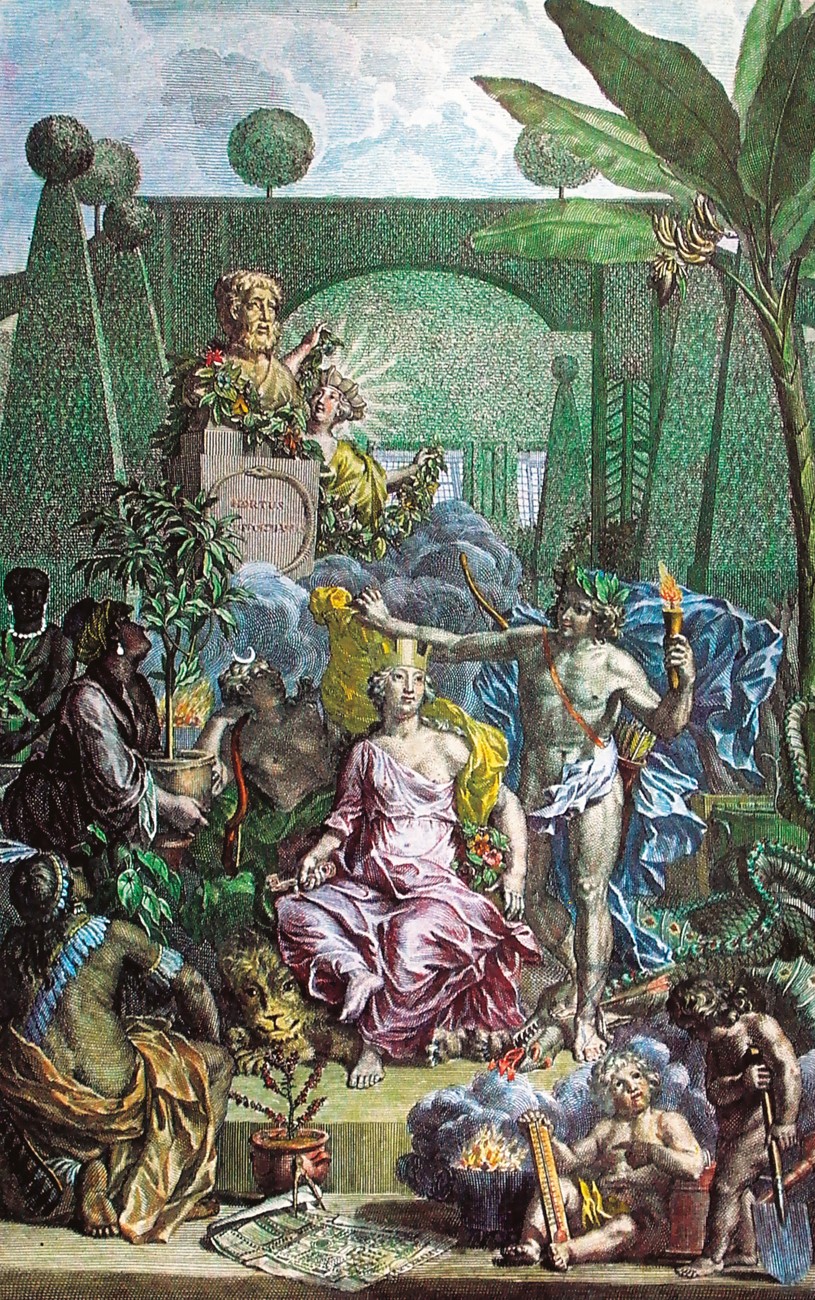

A man not given to modesty, Linnaeus thought of himself in even loftier terms: as the second Adam. “Deus creavit, Linnaeus disposuit,” he liked to say—God created, Linnaeus organised. The frontispiece of his Systema Naturae, his magnum opus, depicts its author in the Garden of Eden, evidently applying Linnaean names to the freshly minted creatures. First published in 1735 as an 11-page tract, Systema Naturae was Linnaeus’s tabulation of the three recognised realms of nature: animals, plants and minerals. He kept adding to it throughout his life, and when the 13th edition was published in 1770, eight years before his death, it had grown to 3000 pages. This multi-volume tome was the last species omnibus ever attempted by a single person. Such was the proliferation of scientific discovery after Linnaeus (in part because his classification system was so comprehensive and easy to use) that no one individual could ever again hope to take nature’s measure.

But how much longer will the Linnaean system last? Recently it has come under attack from taxonomists who believe its structure too inflexible to cope with the explosion of knowledge unleashed by DNA analysis. Today’s Young Turks of taxonomy want to abolish the ranked hierarchy of family, order, class, etc. applied according to strict rules overseen by international boards. Under these rules every group of species must be one or other of a subgenus, a genus, a subfamily, a family, a superfamily, a suborder, an order, etc. It can be difficult to decide what rank a new group should given, and inserting a new group into an existing branch of the taxonomic tree can change the status of other branches. In place of this rigid complexity, the reformers advocate the introduction of clades, less formal groupings which, although still based on relationships, can be expanded, contracted or redefined as new kinships are discovered, and which don’t need to be fitted into a formal hierarchy. For now, though, the traditionalists outrank the iconoclasts, and Linnaean-style classification remains the gold standard. Even if it were to be altered, today’s binomial Latin names or something similar would have to persist. In some senses, much of the turmoil is over the designation of the branches rather than the twigs, and branches are of less concern to gardeners and naturalists than they are to professional taxonomists.

Though Linnaeus’s system in expanded form has endured, his classification criteria barely outlasted his own life. Like his predecessors, he struggled to find universally applicable characters by which to categorise the myriad manifestations of life. Genetics, of course, was unknown: Mendel’s pioneering experiments with peas were still 100 years away. The use of gene sequences, therefore, to determine the relatedness of organisms—the stock-in-trade of taxonomists today—was unavailable to Linnaeus and his contemporaries. Plants and animals were grouped according to appearance—and appearances frequently deceived.

Before Linnaeus, whales were classified with fishes (they possessed fins), and bats with birds (they had wings). To his credit, Linnaeus shifted both bats and whales into the class he invented for all creatures that suckled their young Mammalia. But in many other respects his principal animal categories (Mammalia, Aves, Amphibia, Pisces, Insecta and Vermes) were not much of an advance on Aristotle’s classification. They were broad, catch-all groupings—jumbo bins rather than pigeonholes. For example, the class Vermes, for creatures lacking feet or brains, included not just worms but also molluscs, barnacles, jellyfish, echinoderms and sponges. Classification criteria within the classes were also broad: mammals were grouped according to teeth, toes and teats, fish according to fin bones, and birds according to feet and beaks.

With plants Linnaeus was more particular. Building on the ideas of French botanist Sébastien Vaillant, he based his classification on sexual characteristics. He placed plants in classes according to the number, length and distinctive features of their flower stamens, and in orders according to their pistils.

Linnaeus’s sexual approach was a bold (and, as it turned out, prescient) concept, but one that earned him the ire of his more prudish colleagues. They objected to his lyrical descriptions of the love lives of plants. Bad enough that a flower’s petals should be compared to the “bridal bed . . . perfumed with so many sweet scents in order that the bridegroom and bride may therein celebrate their nuptials with the greater solemnity,” but when Linnaeus defined polyandrous flowers as having “twenty males or more in the same bed as the female,” this was too much. “Who would have thought that bluebells and lilies and onions could be up to such immorality?” jibed one critic, who dismissed the entire system as “loathsome harlotry” unworthy of the Creator.

Linnaeus recognised that his categories were arbitrary and his classification no more than a crude stab at divining nature’s pattern, but they would have to do. Despite the shortcomings of his diagnoses, Linnaeus’s names for the roughly 12,000 organisms he examined over the course of his life became the starting point for modern biological classification.

Binomials—those euphonious Latin names with which gardeners flaunt their erudition—had humble beginnings. They were first used by Linnaeus’s students during a study of the fodder plants preferred by various types of domestic livestock. As they followed the beasts around the paddock, the students needed a speedy method of noting the identity of each plant as it was wrenched out of the ground and swallowed. Binomials provided them with a scientific shorthand equal to the task.

Linnaeus’s theories and methods were always rooted in the real world. At a time when taxonomists were largely an indoor species, inhabiting lecture halls and libraries and scrutinising pressed flowers, pinned insects and pickled vertebrates, Linnaeus was a dirt-under-the-fingernails scientist. For more than 20 years he conducted public excursions in the countryside around Uppsala—possibly the world’s first guided nature walks. He did so partly to supplement the income from his impecunious postings as curator of the Uppsala botanic garden and then as professor of medicine at Uppsala University. Participants (as many as 300 per excursion) paid him in whatever currency they could afford: coins, hats, socks, books, buttons.

What forays they must have been! Botanising with Linnaeus would have been the equivalent of studying geometry with Euclid, or taking a writing class with Shakespeare. In keeping with Linnaeus’s orderly disposition, expeditions were organised with the precision of a military campaign, with designated note takers, specimen collectors and bird shooters. A bugle would sound when a rare species was found. Trophy flowers and butterflies were pinned with pride to the wide-brimmed hats worn by the budding botanisers.

At the end of one of these rambles—which could last up to 12 hours during the Baltic summer months—the party would troop back to town, waving banners, blowing horns and beating kettledrums. Linnaeus led the procession, stopping periodically for last-minute specimen hunting on the sod roofs of the town houses. At the botanic garden a shout would go up: “Vivat Linnaeus!”

In later years these “inquisitions of the pastures,” as Linnaeus called them, had to be curtailed after the rector of Uppsala University protested at the enthusiasm of the participants. “We Swedes are a serious and slow-witted people,” he explained. “We cannot, like others, unite the pleasurable and fun with the serious and useful.”

Linnaeus had no difficulty reconciling the two. For him knowledge and rapture were two sides of the one coin. “The contemplation of nature gives a foretaste of heavenly bliss,” he declared.

[Chapter Break]

Nowhere is Linnaeus’s delight in nature more evident than in the journal of his travels in Lapland, the glacier-carved Arctic region that caps Scandinavia. In 1732, he made a five-month journey to Sweden’s portion of this “land of the midnight sun” to collect specimens and learn how the “happy Lapps”—indigenous Sami people—and Swedish and Finnish homesteaders made use of them. It was arguably the world’s first ethnobotanical expedition.

Linnaeus set out alone on horseback from Uppsala the day before his 25th birthday, equipped with little more than a plant press, a fowling piece, a hand lens and a change of clothes. To stretch the limited funds he had been given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to make the journey, he adopted the local lifestyle, eating reindeer tongues and sleeping in sweltering, smoke-filled Sami huts.

His diary is filled with a young man’s ebullience over the species he encountered and the culture he observed. Charmed by the sight of bog rosemary in full bloom, its blossoms the colour of “a fine female complexion”, he thinks of Andromeda chained to her watery rock, and decides to give the plant genus that name (which it still retains). On learning that Sami bachelors carry about pieces of sweet-smelling mushroom as a kind of cologne-cum-aphrodisiac, he exclaims, “O whimsical Venus! In other parts of the world you must be wooed with coffee and chocolate, preserves and sweets, wines and dainties, jewels and pearls…here you are satisfied with a little withered fungus.”

He admired the Lapps’ resourcefulness. They baked bread made from spruce bark, pine needles, dried fish, moss and seaweed. They had 18 ways of using milk, including “fresh boiled and coagulated with beer” and “mixed with sorrel leaves and preserved till winter in the stomach of a reindeer”. They used the dried roe of pike and char to make dumplings and gruel, and fish oil to waterproof their boots.

The Sami’s healing arts also attracted Linnaeus’s interest, though their drastic cure for headaches sounds more painful than the ache it was supposed to ease: “Place a small piece of fungus on the spot where the pain is greatest, then set fire to it and let it burn till the part is excoriated.”

As he travelled and collected—discovering and eventually naming 100 new species—his thoughts turned to the floristic differences between Lapland and the rest of Sweden, and to the benefits that would accrue if species could be swapped between the two regions. But why stop at botanical rearrangement within the country, Linnaeus wondered; why not borrow from “God’s endless larder” elsewhere in the world?

Other nations had overseas colonies that supplied them with goods they couldn’t produce at home; Sweden could go one better by cultivating the crops of the world within its own territory. Linnaeus believed that acclimatisation, the process by which organisms become habituated to a new environment, could be the engine of economic growth for his “dearest Fatherland”. As his most recent biographer, Lisbet Koerner, writes in Linnaeus: Nature and Nation, the proud Swede sought to “re-create within his national borders a trans-oceanic empire”.

Back in Uppsala, he became obsessed with the idea of cinnamon groves and tea plantations flourishing under a Baltic sun. Unswerving in his belief that any plant could be “tamed” to withstand a more rigorous climate, he looked to a day when fashionable Europeans would wear Swedish silk, drink Swedish coffee and eat Swedish rice. (Who knows, global warming may yet produce such a scenario.)

In the interim, Linnaeus exhorted his fellow Swedes to adopt local substitutes for imported luxuries: bean sauce instead of soy, faux coffee made from burnt peas, almonds or toasted bread. Guinea pigs, “slaughtered, shaved and fried,” would make an excellent indigenous meat source, he said. His substitutionary eye missed no opportunity. Let elk rather than horses pull ploughs, he suggested—and proceeded to try to tame one for this purpose.

He sent his students—“apostles”, he called them—to the far corners of the globe to look for species with the economic potential to make Sweden the financial powerhouse of Europe. Two of them visited New Zealand: Daniel Solander, who assisted Joseph Banks on Cook’s Endeavour voyage, and Anders Sparrman, who was on board Resolution during Cook’s second round-the-world voyage (see sidebar). When scientists today scour tropical rainforests for pest-resistant plants or organisms which might hold the key to curing cancer, they are doing precisely what Linnaeus bid his students do: inventory nature and identify her riches.

Of all his horticultural notions, it was tea that most captured Linnaeus’s imagination. It irked him that for “just a couple of leaves from a bush” Europe squandered its wealth. He begged his students to bring him live tea plants from abroad, confident that he could get them to grow in a colder climate. Until such time as Swedish tea became a reality, he recommended home-grown alternatives such as lemongrass, speedwell, bog myrtle, Arctic raspberry and marijuana (which he praised for “chasing away melancholy”). To damp down demand for imported tea, he railed against the beverage, saying it made “the nerves flabby, the head stupid and the body feeble”.

Fired by patriotic zeal and a naive confidence in the adaptability of nature, Linnaeus worked tirelessly to establish his dream plants in the cold Baltic soil. And when he wasn’t tending mulberry bushes or sprouting cardamom seeds he dabbled in aquaculture, successfully growing pearls in freshwater mussels, discovered the principles of dendroclimatography—that tree rings date trees and record past weather patterns—and gave an important tweak to the Celsius scale of temperature measurement. Anders Celsius, a contemporary of Linnaeus, had designated the boiling point of water to be 0 degrees and the melting point of ice to be 100. It was Linnaeus’s idea to flip the scale.

Ultimately, Linnaeus was mistaken in his view that plants were globally interchangeable—a conclusion he reluctantly came to accept after most of his horticultural transplants had failed. (A notable exception was rhubarb, a native of Asia, whose introduction to Sweden he called his proudest achievement.) Linnaeus was also wildly wrong about the number of living species. He thought there might be around 40,000 all told; estimates today range from 10 to 100 million.

However, many of his other views were accurate, and surprisingly modern. He foreshadowed Darwin in his belief in a universal struggle for survival. He was the first to classify humans with other primates and gave us the name Homo sapiens. He advocated biological control as a means of dealing with insect pests (he was particularly keen to find the invertebrate “lion” that would control bedbugs), and he understood the importance of biodiversity: “I do not know how the world could persist gracefully if but a single animal species were to vanish from it,” he wrote in his journal. He even conjectured that micro‑organisms “smaller than the motes dancing in a beam of light” might be responsible for transmitting contagious diseases—long before medicine embraced the idea of pathogens.

On the other hand, Linnaeus was deeply suspicious of the modern world, and wrote lengthy lists of decadent luxuries to be avoided, among them chocolate, almond cakes, oysters, raisins, mousses and jellies, wallpaper, clocks, oil paintings, card games, wax candles and silk stockings. Scandinavians, he said, should return to a diet of acorns, pork and mead.

Many of his ideas now seem ludicrously archaic. He believed epilepsy could be caused by washing one’s hair and leprosy caught by eating herring worms. His ideas about nature could be equally primitive: he persisted in the archaic belief that swallows overwintered at the bottom of lakes.Some of his notions were simply quaint, such as a floral clock he devised, based on the known opening and closing times of various flowers.

[Chapter Break]

Though he didn’t follow his father into the ministry, Linnaeus remained a devout Lutheran throughout his life, despite the clash of his theological views with his scientific conclusions. Faith led him to believe that human beings were “candles in God’s palace”, reflecting the “creator’s shining majesty”. Science took him to a far bleaker conclusion. “Pathologically,” he wrote, “you are a swollen bubble till you burst, dangling from a single strand of hair in one brief moment of fleeting time.” The man who classified the living world even wondered why there was any diversity in nature at all. Why did the creator not make the earth out of cheese, he mused, “which we worms could have gnawed while we grew up, lived, and multiplied?”

Linnaeus struggled with pendulum-like swings between exuberance and depression, ego and angst. At one moment he was God’s chosen instrument, whose science was “the light that will lead the people who wander in darkness”, whose literary oeuvre was “a masterpiece that no one can read too often or admire too much”. At the next he was a miserable failure. “Had I had rope and English courage,” he wrote to a colleague, “I should long ago have hanged myself.” Even when he was made a member of the Swedish nobility in 1762, taking the name von Linné, he chose as part of his heraldic emblem an unprepossessing Lapland flower called Linnaea borealis—a plant named after him. He describes the delicate species as “lowly, insignificant, disregarded, flowering but for a brief space”, adding that it was named “from Linnaeus, who resembles it”.

His conception of a vengeful deity didn’t help his equanimity. Ever the cataloguer, he collated a file of some 200 instances of what he considered divine retribution meted out to errant mortals. Published after his death, Nemesis divina pictures a fire-and-brimstone deity not unlike Gary Larson’s caricature of God at his computer, forefinger poised over the SMITE key. The self-doubting Linnaeus never outgrew his dread that the finger was about to fall.

During his bouts of melancholy his family was a consolation (he was a devoted father to his seven children, only five of whom survived early childhood), as were his pets, especially his guenon monkey, Diana, and a raccoon named Sjubb. And he could always turn to his beloved plants for comfort. “I have no time to think of illness,” he scribbled. “Flora comes hastening with all her beautiful companions.”

Such unquenchable joy in nature is one of the most appealing qualities of the man, and one of the reasons Swedes venerate him. May 23, Linnaeus Day, is an occasion for parades in the streets of Uppsala and Råshult, Linnaeus’s birthplace, to honour the “flower king of Scandinavia”. One Uppsala café specialises in baking Linnaeus cream cakes, iced with his silhouette, and there have been celebratory bottlings of Linnaeus liqueur—the better to toast the inventor of science’s universal language, nature’s chief librarian, and, as one of his contemporaries described him, “the most compleat naturalist the world has ever seen”.

The father of modern taxonomy is buried in Uppsala cathedral. Fittingly, a bronze plaque marking the spot is engraved with a binomial description of the man whose bones lie beneath: Princeps botanicorum, the prince of botanists.