Buried treasure

For palaeontologists, the dark diatomite layers of Foulden Maar are like the shelves of a great library. Outside that library, bulldozers wait.

Whatever this is, it is not Otago. It might be Queensland, by the look of all those palms and vines and outrageous orchids. Of course, they’re not called orchids yet. Nothing is called anything, because there won’t be anything like a human for another 18 million years. But eventually, they’ll name this piece of flotsam Zealandia, a place barely treading water.

Some of this stuff seems familiar. Those podocarps, for instance, and the mistletoes, and those distant hills covered in what would be southern beech, if there were any concept of south. This looks like a fuchsia, and there’s no mistaking the spiders. Any comfort of recognition, though, is swamped by the noise and shudder of change: the violence of the rain and the sooty fume of volcanoes. Every tremor sets the sky darker with shrieking birds. This jungle looks permanent, but it’s an interim measure: the land on which it stands is yet to congeal.

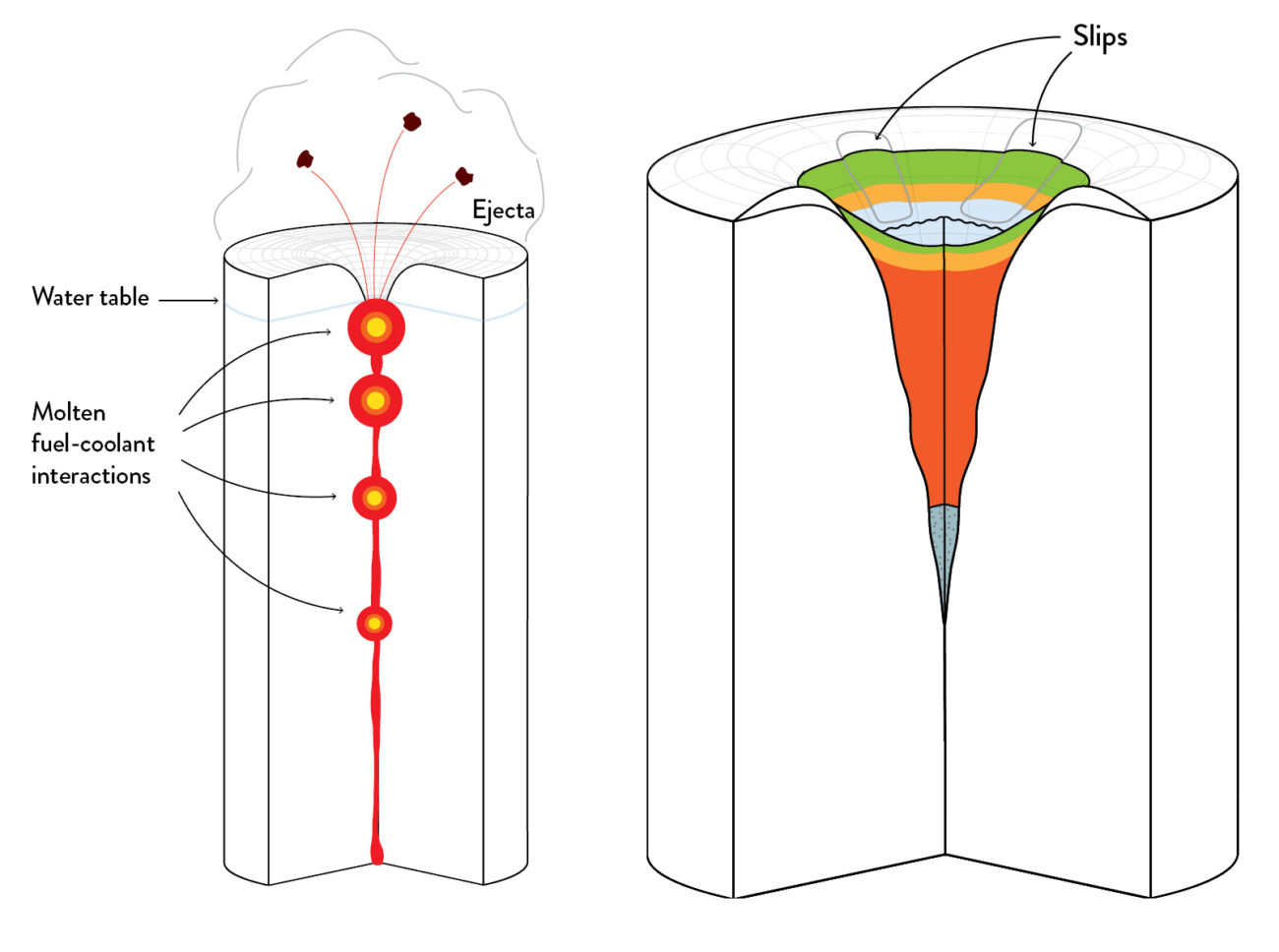

That lake, for instance, barely a kilometre across. It was created in a flash, literally, when an artery of broiling magma muscled up through the crust, driving for the surface. With 100 metres still to go, the magma struck an aquifer instead. Millions of litres of water vaporised into superheated gases, flexing against their tomb until the land was blown high into the air. The bigger rubble fell back into the red raw crater, while atomised rock and ash wafted wider, then settled to cover the open wound.

Before long, the steaming vent was extinguished, filled by rain. The forest took root anew in the ringplain of lush volcanic jetsam, or as Nic Rawlence would call it, 23 million years later, tuff.

“That massive, violent explosion,” explains Rawlence, director of the University of Otago’s palaeogenetics lab, “also exerts downwards, almost like depth charges, so that you get a crater that looks like a massive ice cream cone shoved into the ground.”

Geologists call these maars, and they’re found around the world. (Many of the crater lakes around Auckland, such as Pupuke, are maar lakes.)

The rim of tuff around the ice cream cone blocked any streams from running into it. Over time, this rainwater lake mummified into New Zealand’s richest trove of fossils, now known as Foulden Maar.

“You effectively had the perfect closed system,” says Rawlence. “The upper waters will be oxygenated, but the deeper ones were anoxic.”

Twenty-three million years ago, diatoms—freshwater algae—bloomed at Foulden Maar in the subtropical summer. When they died in the cooling waters of autumn, their millions of single-celled corpses sank to that airless floor, burying other bodies—insects and fish, plus leaves, flowers and pollen from the surrounding rainforest. Then they repeated the cycle another 120,000 times.

With no currents to disturb them, no oxygen to rot them, no necrophages to eat them, and a fine blanket of diatoms to cover them, Foulden’s dead are among the most perfectly preserved fossils anywhere.

The lake, the palms, the orchids are long gone. Here and there, clumps of matagouri dot the paddocks, and the odd tōtara stands as a monument to the once-great podocarp tracts. The swirling clouds of birds are now starlings. The volcanoes of the Waipiata Field stilled millions of years ago, but curvy caps of basalt top some of the nearby hills.

Barely five minutes east-southeast of Middlemarch, Foulden Maar is a dip in the middle of a paddock, so anodyne that when Daphne Lee first laid eyes on it in the late 1970s, her curiosity remained stubbornly unpiqued.

“I didn’t take it very seriously. It was long before we realised it was a maar deposit. We had no idea.”

In 2003, Lee, now an honorary associate professor at the University of Otago, went back. “The previous mining company had cut a fresh face about five metres deep, so we could see the diatomite layering much more clearly.”

The team drilled a 184-metre-deep core sample. Its harlequin hues were a teaser for one of the most dramatic stories in New Zealand palaeontology.

“That was the first time anyone could prove this was a maar deposit,” recalls Lee, “and that opened up the climate record.”

She’s led the research effort at Foulden ever since.

Geologically, New Zealand’s had a rough time of it—volcanism, tectonic rifting, subduction, submergence, glaciations—which partly explains a historic dearth of good fossils.

“When we first started work at Foulden, there was a total of maybe seven pre-Ice Age insect fossils known from New Zealand,” says Lee, “and they were grubby little bits of beetle that couldn’t be identified properly. That was it. We had a virtual black hole in terms of the fossil record.”

Since then, postdoctoral fellow Uwe Kaulfuss has found 266 insect fossils at Foulden Maar. “And almost all of them are different,” says Lee. “They include termites and ants and beetles, and crane flies and caddisflies.”

Spiders are especially rare as fossils, but Foulden has yielded four. All the arthropod fossils are new species.

“It’s opened up a treasure chest, in terms of our understanding of the terrestrial arthropods in New Zealand.”

But Foulden is about quality as much as quantity.

“Because there was so very little decay down there, little things, like eyes, are preserved, and wings, and antennae—incredibly delicate structures beautifully preserved. It’s just extraordinary.”

That detail, says Rawlence, gives us much more than a list of species.

[sidebar-1]

“You’re not just preserving leaves, you’re preserving the scale insects that lived on those leaves, and you’re preserving them in life position. This isn’t just a bunch of skeletal ghosts—it’s a record of that much rarer behaviour, a glimpse into how the ecosystem functioned.”

Foulden immortalised its dead so gently that Lee’s team has found fossil flowers with pollen grains still on their anthers.

“Intact fossil flowers are almost unheard of, because they’re normally so fragile.”

Because pollen blows on the wind, it’s found in fossil deposits everywhere, says Lee.

“So it’s really hard to track it back to the parent plant. But if you find the pollen in the flower, that opens up a huge window of information about the ecology of pollination, and the families of plants that were present in New Zealand back then. Many of them are now extinct in New Zealand.”

But it was a few leaves that really put Foulden on the map.

“I didn’t think much of them, but a colleague got very excited about them,” says Lee. “He sent the photographs to Kew Gardens in London, who confirmed that they were fossil orchids. That might not sound terribly exciting, but there are something like 20,000 living species of orchids, and only three orchid fossils in the world.”

Foulden has boosted that to five. “That one find has an enduring global significance. Now, everyone in the world who writes about fossil orchids cites our work at Foulden Maar.”

There are pieces of fossil jigsaw scattered across present-day Otago, thanks to much of it being drowned by Lake Manuherikia, just a few million years after the Foulden crater blew. Manuherikia was 10 times bigger than Taupō Moana: it swamped 5600 square kilometres, from the Māniototo to Roxburgh, the Nevis Valley and Wanaka.

While no outward hint remains of the subtropical rainforests that once clad the downs around Foulden Maar, pictured on pages 96-97, the dark, diatomite soils below are revealing an exquisitely preserved archive from a time when biodiversity ran riot, 23 million years ago.

Excavations at St Bathans offer flashbacks that look like a tantalising match with Foulden: casuarinas, eucalypts, palms, and cycads. But it’s St Bathans’ menagerie that has palaeontologists fizzing—three-metre-long crocodiles, turtles, giant burrowing bats, and the prized exhibit: a mouse-sized mammal.

There’s a lot riding on this waddling mouse. We’ve always assumed that Aotearoa’s birds evolved to fill terrestrial niches in the conspicuous absence of ground-dwelling mammals. The St Bathans find could turn this hallowed tenet on its head, but the fossil isn’t complete enough to know for sure—some researchers have suggested it could just be another bat, and we already knew about those.

Foulden’s greatest promise lies in the real possibility that it might, courtesy of its gorgeous record, settle that debate, and many others.

“If there was a land mammal that wasn’t a bat, Foulden could be the place to find it,” says Lee. “It would be good to find the whole thing to put it to rest. That’d be very exciting.”

In this way, Foulden Maar could literally put flesh on the bones of New Zealand’s past. At 23 million years old, it promises a prologue to stories partly told, says Rawlence, by Hindon Maar, which is around 15 million years old, and St Bathans, which is between 16 and 19 million years old.

“They basically preserve different snapshots of New Zealand at different times.”

St Bathans has revealed a rich bird fauna, but mostly with glimpses of odd bones. Lee says Foulden could show us much more: “It’ll likely reveal entire birds, with feathers intact. We’ve already found feathers at Hindon Maar. We know that the preservation of feathers is very likely.”

Nic Rawlence agrees. “The preservation conditions are right, as we’ve seen from the fossils of the fish and the leaves.”

He points out that maars overseas, such as the Messel Pit in Germany, have produced beautifully intact bird fossils: “So we would expect them here, too. It’s just a matter of finding them.”

It’s hard to overstate the potential of Foulden Maar. Palaeontologists have barely started work. The dig, maybe the size of a tennis court, represents “a teaspoon from a rugby field”, says Rawlence. Yet it’s already dramatically illuminated our understanding of early Aotearoa. Its gifts so far have been so generous that it will take, says Lee, decades to properly process and describe them.

“We lack the taxonomists to process and describe all these finds, so we work with international experts. The insects in particular are so diverse that we need global help with their description. That’s the only way this can be done.”

But others covet the maar’s treasures, too. It lies on private land, which since 2015 has been in the possession of majority Malaysian-owned mining company Plaman Resources, which wants to dig up all those billions of dead diatoms and sell them for pig food, and fertiliser to the palm oil industry. The diatomaceous deposits of the maar were long considered uneconomic—ironically, Plaman’s bid was motivated by the scientists’ core sample, which showed the maar’s diatomite reserves were to six times larger than previously thought, and so flipped the site over into viability. But the company can reach the entire deposit only by buying a neighbouring property. In May 2018, it lodged an application to the Overseas Investment Office for that purchase. As this magazine went to print, the OIO was still adjudicating.

Lee and Rawlence have spoken passionately in defence of Foulden. Its destruction would be akin to demolishing Te Papa with the exhibits still inside.

Lee says she will fight the proposal “to the bitter end”. Rawlence points out that the Messel Pit in Germany is protected by a UNESCO World Heritage Listing. If Foulden were to be similarly safeguarded, he says, there would be the opportunity to involve the public.

“It’s the type of site where you could take your grandparents, take your small kids and you could find fossils really easily. The amount of palaeotourism that you could do at this site would be phenomenal, and so much more economically and ecologically sustainable than mining it for pig food.”

Shortly before this story went to press, Plaman Resources went into receivership, and while the OIO was quick to point out that didn’t mean the end of the purchase application, it almost certainly killed it. But Foulden Maar is not saved: Plaman’s receivers said they would consider recapitalisation, as well as “full or partial sale of the company’s assets”.

As former Prime Minister Helen Clark told reporters in June: “It’s a question of values. Do we value knowledge? Do we value natural heritage? Do we value science and research? Or do we just want a quick dollar from a low-value pit? I mean, really, it’s distressing.”