Art and the spirit

Darkness. And the shuffling of the crowd around me. Excitement hangs over us, sparkling faintly in the whispers and coughs, the yawns and murmurs — soft, with the dawn. We wait. Then, begin to move. Forward, slowly, all of us, behind her. And behind the old man whose voice lifts and soars, lifts and soars, cutting through the dark, clearing the way.

They pause at the door, that special group, there in front of our fumbling, tense, rippling mass. They are so still. Like we are meant to be, try to be.

A question is asked, and the name is given.

With a sigh the door slides open, while the karanga, the mourning, keening, gripping chant-cry of the kuia, the old women, fills the cool air around us.

And suddenly there is light, a radiant flood of light, pouring through the windows, spilling on to the verandah, gracing the rafters. Light from the ceilings; light from the eastern skies.

We all gasp — a long, collective, loving gasp — at the beauty of this new house, so rich, so splendid, so warm. Carved images prance and smile and reach out for us from the walls while panels of lattice tukutuku weaving lock them firmly into place. Overhead, the rafters stretch wide, protecting us with their smoothly flowing patterns, and, beneath our feet, finely woven fibre mats cover the floor.

The new house is ours, from them — another gift. From the artistry of our ancestors, from the certainty of their knowledge, from the strength of their spirit.

He oranga ngakau mo to iwi — a source of pride for us.

[chapter-break]

Taha wairua, the way of the spirit in matters Maori, permeates our world so profoundly that to isolate and analyse it is almost like threatening the very fabric itself. Spirituality and artmaking have formed an integral part of the Maori world view from ancient times until the present day.

The early voyagers from the central Pacific settled this land over a period of four or five hundred years. Oral tradition tells us that the final landfall probably occurred some time after 1400, yet the very first food was eaten on these shores in the tenth century, over a thousand years ago.

Guiding those great ocean-going canoes and ensuring a successful journey were a myriad of supernatural beings, creatures of wairua brought from Hawaiki Nui, the home‑land. Some were carried in the form of tokens and talismans, but most were conveyed silently and secretly, in the hearts of the people.

With the new land’s abundant resources of stone and fibre, wood and feather, bone and shell, the settlers’ hearts were opened, and their creative imagination flourished. Divine inspiration shaped those very first taonga tuku iho, treasures of the ancestors, that are revered, cherished, and admired today. And thus the spirit thrived.

In contrast to the islands of origin, this new land offered vast wealth: colossal trees for house and canoe building and ornamentation; prolific bird life providing masses of food and decorative feathers; huge river-hewn quarries of jade; long ocean beaches stranding disoriented whales; cliffs of glittering obsidian; vast tracts of supple, shining flax plants. More than enough to compensate the loss of the aute — paper mulberry for Papa cloth — and hara — the sturdy pandanus for weaving. Though cold in winter, the land was an incredibly plentiful resource; Papatuanuku, Mother Earth, gave generously.

And as she gave, so her gifts, ultimately, were returned. Every art piece or artefact made before 1800, and certainly most since then, has been a tribute to the natural world. Although fashioned by human hands, the taonga remain sourced within the environment. An elaborately carved war canoe will typically be a gigantic totara or kauri tree, enhanced by paua shell and toroa feathers, resin, supplejack and flax fibre. With time and circumstance these materials may once more become part of Papatuanuku, to be folded within her earthen self. Awareness of this possibility is constantly acknowledged by the people.

Similarly, great houses are seen as living entities rising from the earth — even now, despite the inclusion of introduced materials and technology. Like canoes, great houses can travel, get dismantled for long periods, be concealed deliberately and carefully, or find themselves falling, easily and miserably, back into the ground. But whatever may happen to the material form, the wairua, the spirit, of the taonga remains with the natural world, with the environment, with the land.

The old-time Maori lived with a stone age technology. The impact of metal upon the material culture the arts, warfare, architecture — was dramatic, even devastating. Adaptation was immediate, especially in whakairo, the carver’s art. Stories of nails meticulously removed from ships’ decks are no doubt true. These nails became the first metal chisels and transformed the face of traditional carving, just as musketry disfigured the subtle nuances of warfare. But whatever the means employed, the inspiration and the genius still came from the spirit.

Wairua was surely a realm of great beauty. The ancient Maori was an ardent lover of beauty in the natural environment and in any manufactured reflection of that world. Beauty was, and has remained, an essential quality of Maori life. It is a mirror of the inner self, imbuing even the most functional object with specialness and spirit. Even very mundane items — eating bowls and utensils, baskets, gardening tools, mats, fishing sinkers and fishhooks, chisels, bird troughs and canoe bailers — were gracefully designed and craftily decorated. Everything, no matter how simple, had to be pleasing to the eye and touch.

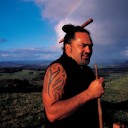

Which brings us to fashion — to the supreme beauty-consciousness of the early Maori and their enjoyment of elaborate dress, complex (and usually permanent) facial make-up, and a dazzling display of jewellery and accessories.

The first Pakeha explorers noted the richness of chiefly costume and the regal manner of their bearing; their immaculately dressed hair fastened by combs of wood or bone; their glowing pendants and curious amulets of polished nephrite; their shimmering fibre cloaks and brightly textured dogskin wraps; their haughty faces golden brown beneath a swirl of chiseled indigo. Balance a harmony of textures, colours and tones — was essential to achieve the appropriate effect, and, more importantly, to move within the flow of the natural world. For the fashionable chief reflected his or her environment, and therefore had to be aligned with it. Every piece of the well-dressed Maori’s wardrobe had a significance, an essential mauri, or life force, which linked the taonga to the natural world, and in the end, to Papatuanuku herself.

Balance was also a vital element in weaponry. The first settlers brought with them from Hawaiki the original patu shape — the short, hand-jabbing weapon of Polynesia. Here the form blossomed. Crafted from jade, hardwood, basalt or whalebone, and used like a thrusting short sword, the patu had a simplicity ornamented only by its grip. The medium would determine the complexity of design. Mere pounamu, greenstone clubs, are thus deceptively clean and unadorned, yet balanced with lethal accuracy; patu paraoa, made from softer whalebone, often feature elaborate bird forms and shell inlay, or carved manaia profiles. Elegant and deadly, such beauty would inspire courage and bolster the warrior’s spirit.

Each weapon, whether a jabbing patu or a striking taiaha, longstaff, had its own name and identity; not only from its function and the material it was made from, but, more significantly, from its custodian and wielder. All prized Maori artefacts acquire power from those many people who have looked after and enjoyed them.

Related again to the natural world are the design forms taken by the taonga. Within the plaited complexity of taniko weaving and tukutuku wall panels are the flounder shapes of patiki, the wavy chevrons of aramoana, the twinkling stars of purapura whetu. Kowhaiwhai rafter painting recalls unfurling fern leaves, sinuous shark shapes, budding flowers and gaping seed pods. Artists followed a cycle of acquiring raw materials — wood, fibre, or some other making the taonga, and then, to complete the transformation from resource material to manufactured item, applying in decorative form a reference to the taonga’s source. Like a spiral, one of the art’s most common yet potent symbols, the taonga turns back to its beginning, back to itself.

Up until now I have referred to taonga using the word “it”, when for most, if not all, Maori, taonga are living entities, best addressed as “her” or “him”, or, ideally, by a personal name. The impersonal pronoun neutralises an artefact, not only demeaning the power within, but distancing the treasure from the beholder, the toucher, the caregiver. The relationship that Maori enjoy and cultivate with taonga tuku iho is of major importance. A carved house truly does embody a revered ancestor; a great canoe actually personifies a concept, a vision, that motivates the people. Even the tiniest pieces demand this firm regard: one of the daintiest, most delicate taonga in the fabled Te Maori exhibition — a tiny bone earring — was among the most memorable. Despite her size, she ached with the quiet power of all those generations who had fondled and coveted, touched and admired her unusual beauty.

For the Maori people and, specifically, for this Maori person, ancestral art holds many different meanings. The taonga inspire and confront; they relax and soothe; they provoke and energise; they empower and sustain. They convey memories from the past and make promises for the future. They tell us where we, as a people, have come from, and they show us where we are going to. They represent hope, fortitude and resilience: the survival of spirit.

Over the last two hundred years much has been utterly, irretrievably lost — deliberately burned in the name of Christendom, recklessly smashed by colonial expansion. Carved structures flattened, sacred sites desecrated. In some regions it is said the visual arts vanished altogether. Yet the embers stayed warm and the wairua remained. In spite of the bitterness of land confiscation, introduced epidemic diseases and language loss, those plundered generations survived, and beneath the ravaging pressures of the nineteenth century, they created some of the finest, most fabulous taonga we have. The legacy of that troubled, desperate time to this one is one of genius, of adaptation, of energetic and extraordinary artmaking.

And what will be our legacy to the next generation, as we move into the third millenium?

The ancestral art forms, and their making, have been successfully retained and fostered, though not without considerable struggle and the grim determination of remarkable individuals. Rangimarie Hetet, the doyenne of Maori fibre art and garment manufacture, continues to inspire, motivate, and encourage; her own family, and their many scores of students, celebrate the tradition and reinforce its continuity. The artistic offspring of such tohunga as Piri Poutapu and the brothers Taiapa still enthrall contemporary Aotearoa with spectacular houses and superb canoes. And, predictably, as the cultures of this land entangle, convolute, merge, or parallel, new art forms and new artmakers rise to the surface from within the Maori world.

The wairua lives on: a new beginning… and another story.