Arctic impressions

It is probably not that surprising that my coldest, longest and most severe journey was conceived in the warmth and security of a hot tub.That’s often how it is with extreme physical challenges. You don’t tend to plan these acutely uncomfortable experiences when you’re hanging by your fingernails from some icy mountain crag. It’s only afterwards that the five per cent of pleasure bubbles to the surface through the ninety-five per cent of pain and drudgery that make up the average expedition. But it is that pure, unsullied pleasure that sticks in the mind and tempts you to go to the edge one more time.

Three years after that particular soak—having survived the horrors of fundraising, the frustrations of permission seeking, the embarrassment of equipment bludging, some mind-bending personal problems and about 20,000 kilometres of the Arctic—I was alone in my tiny yellow tent in northern Canada.

It was the beginning of April, 1993. My camp was a pin-prick of colour in a desert of terrible white. Beneath the thin tent fabric the metre-thick sea ice crunched and groaned with the tide, and below the ice was the freezing sea of the Northwest Passage. The temperature was brutal at minus 41 degrees Celsius. Moments before, I had put a mug of recently hot tea to my lips to find it frozen solid.

My body was cocooned in many layers: polypropylene next to the skin, a woollen sweater, a thin down suit, a thick down suit, polar boots, balaclava, huge mitts, and encasing the lot a large over-stuffed mummy sleeping bag which gave me the posture, bulk and athleticism of a quadriplegic walrus. A recently devoured boil-in-the-bag Irish stew was a warm pool in the recesses of my body.

On one side of the mass that was me, my short-barrelled Remington shotgun (designed as an anti-terrorist weapon) graced the floor of the tent. On the other side lay a knife that made Crocodile Dundee’s look like a tooth pick. These implements were hardly for decoration, but had a polar bear shown up in the middle of the night the party would probably have been over before I had removed my mitts and found the draw-string of my sleeping bag.

I was bone weary, but couldn’t sleep, so with my breath building a small glacier around the tiny opening in my sleeping bag hood, I considered the trip thus far . .

[Chapter-Break]

Our first attempt to set out on a complete circuit of the Arctic was in early March 1992. It was a dismal and embarrassing disaster when our three Russiamade snow machines and two sledges failed mechanically within 50 kilometres of the start point. Two weeks later we tried again.

In the main group were Kim Price, an outdoors instructor from Rotorua, Tolya Chernishov, a Russian former submarine weapons technologist now turned businessman, and me. We were supported by a small crew of New Zealanders and Russians under the leadership of Alexei Krylov and Annie Bradshaw.

In general terms our objective was to make the first complete circuit of the Arctic, keeping to the surface between latitudes 60 and 75 degrees north.

When we finally began west across Siberia, we had swapped our clapped-out snow machines for a noisy Russian tank-like ex-military troop carrier that delivered a ride which can be compared in smoothness to a mobile tumble polisher and a locomotive-powered vibrator combined. The machine’s master, Sasha Sezganov, was an indomitable Cossack with a mouthful of gold teeth who, in spite of the almost insurmountable problems of nature and mechanics, never wavered in his determination to assist our mission.

The immensity and harshness of northern Siberia in winter defies description. Alaska, the largest American state, would make a relatively minor impression if it were uplifted and dumped in the middle of Siberia.

It is a land that can only be crossed in winter when the freeze locks up the rivers, seas, lakes and endless tundra bogs.Once break-up comes in early May, it is impossible to travel far. So our initial challenge was to get from the Bering Strait to the Yenisey River before the ice broke up. If we failed to do this, our journey would be over.

As we clattered 8000 kilometres across that frozen land we were surprised to discover that it was relatively well populated. Despite the harshness, there were small hamlets of friendly people every few hundred kilometres—here a village of hunters and reindeer herders, there a gold mine or weather station. Hospitality was universal. No matter what time we arrived at habitation, day or night, we were fed and given a bed.

There was only one village where the local authority refused to sell us fuel. The man in charge had said, “We won’t help you because the last expedition here in 1948 left a disease.”

Some of the bigger towns such as Pevek, Tiksi and Norilsk/Dudinka, had been the appalling Stalinist gulags where millions had died as slaves of one of the most inhuman tyrants ever to walk the earth. But the sons and daughters of the prisoners showed us nothing but kindness, despite their own poverty and lack of security. Around them the communist regime had imploded into a vacuum of indecision as both the authorities and the general population grappled stoically with the meaning of the new phenomenon called capitalism.

We stopped at a number of installations and mines where the people had not been paid for months and no longer knew who they worked for or even who owned the products of their labour. The average Russian’s patience and trust seemed inexhaustible, and we never once saw frustration at the appalling state of affairs.

I had the impression of a land sorely tested by both nature and people. There was a scarcity of wildlife, but this alone was not evidence of abuse as we saw little life anywhere in the high Arctic in winter. We met scientists measuring abnormal levels of heavy metals; we passed villages where spontaneous nosebleeds and mysterious rashes were blamed by the locals on nuclear testing; we saw on the outskirts of almost every town huge trash dumps of disused oil drums and metal junk.The sea. we were told, was just as polluted.

[Chapter-Break]

We were luckey with the ice. We reached Dudinka on the Yenisey River just as break-up began, and discovered in port a giant cargo-carrying atomic icebreaker bound for Murmansk. The skipper kindly agreed to take us with him.

From Murmansk, we reached Greenland on board a small Russian research vessel via the Barents Sea, one of the few parts of the Arctic Ocean which don’t freeze. The ship’s oceanographer, Oleg Sochnev, told us that this important spawning area, where the Arctic Ocean mingles with the Gulf Stream, was on the brink of ecological collapse as a result of the dumping of atomic and industrial waste, undersea explosions, overfishing and the constant traffic of heavy vessels over fragile spawning beds.

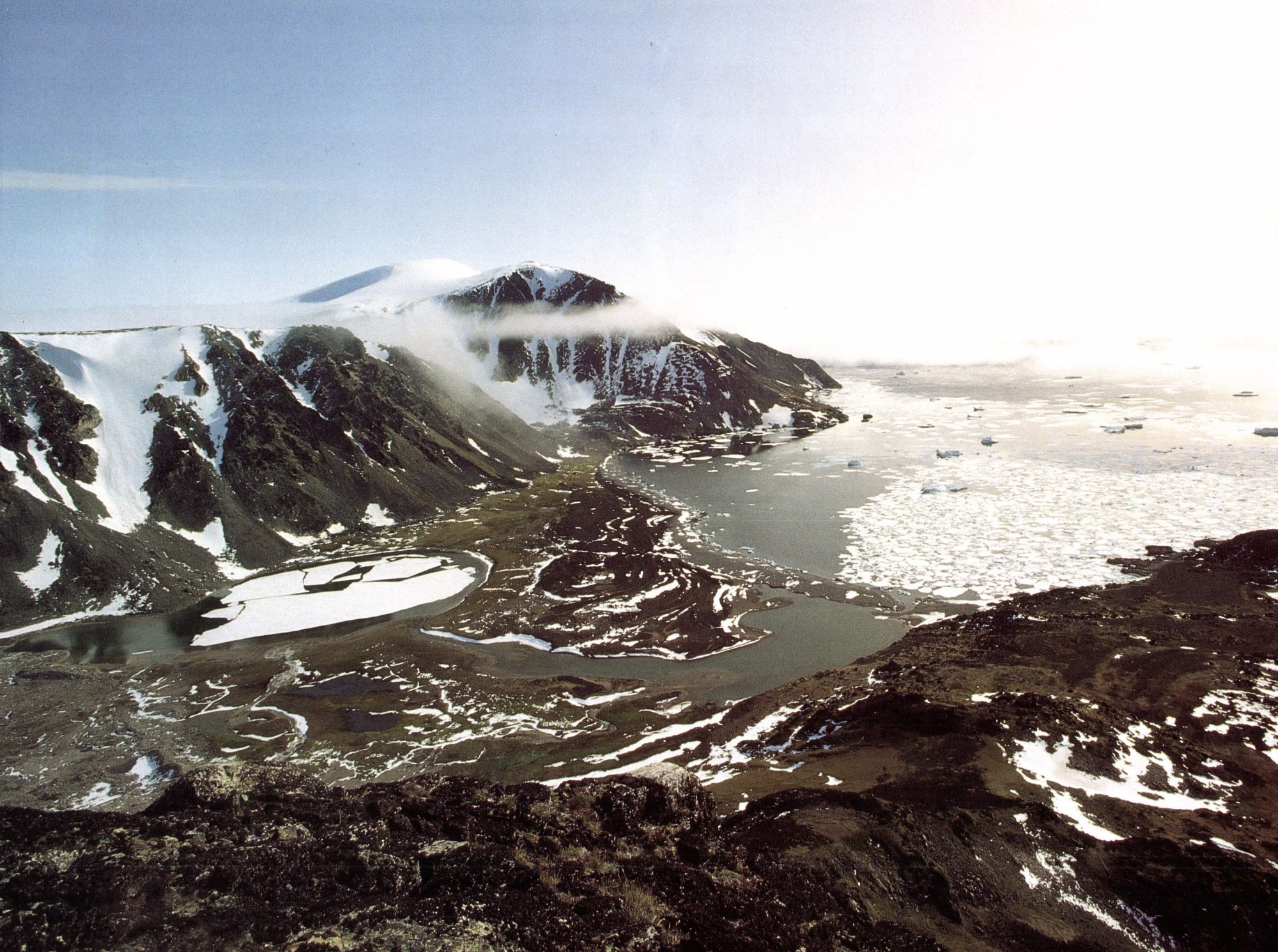

We travelled frenetically up Greenland’s icy west coast in a six-metre Lancer inflatable, loudly denying any link with Greenpeace, who seemed to be universally hated by the locals for crippling the seal fur industry. We were aided enormously by publicity we received for rescuing five people from certain death when their launch sank after hitting a rock eight kilometres off the coast.

But our own luck ran out near the mouth of the Northwest Passage. It had been the longest winter for more than 200 years, and the ice in the narrow channels of the Passage had not broken up. While we could push through loose brash ice in the inflatable, more solid stuff was impossible. The Passage was too ice-clogged for a boat and too unstable to traverse by foot. The journey had to be temporarily abandoned.

Although we had achieved what was probably the longest continuous Arctic journey ever done (19,000 kilometres), we felt cheated. Even our stoical Russian, Tolya, vented his disappointment, using the universal language of exasperation: “Buwlshiit!”

Tolya returned to Moscow and Kim and I to New Zealand. For my two friends, shortage of funds and other commitments precluded them from continuing once the next winter had frozen the sea solid again, but for me, the journey could only be over when I had been right around the Arctic and again reached Cape Dezhnev where we had begun.

As well as wanting to finish the job, I felt I had to continue the journey as part of a personal search for something. Peace? Meaning? Something in that frozen whiteness seemed to call me—sort of like a modern 40 days in the wilderness.

In February 1993 I returned to the mouth of the Northwest Passage. At Resolute I bought a bright pink snow machine and an eastern Arctic sledge, or kamatik, as the Inuit call them. The previous owner of the snow machine, Bezel Jesudason, was an Indian from Madras who had lived in the Arctic for more than 20 years. Before I left he said. “I hope you’re mechanically minded, because these things don’t work for white men.”

I spent a couple of weeks becoming familiar with the machine and sledge, then headed east on the sea ice of Lancaster Sound until the sight of open water scared me back to Resolute.

Lancaster Sound was the lion’s mouth into which so many ships had entered in an attempt to unravel the key to the Northwest Passage, the fabled sea route linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Hundreds had died ghastly deaths at the hands of the ice and malnutrition before that polar genius Roald Amundsen finally navigated the small ship Gjoa through the Passage between 1903 and 1906. Eighty-seven years after Amundsen, I would attempt to do the first transit of his route by snow machine.

But I was so awed by the cold, the fear of thin ice and open water that, with Bezal’s help, I persuaded a local Inuit named Oodlat Naluk to accompany me to the first village, Spence Bay (Taloyoak).

In a straight line it was about 700 kilometres, but zig zags to avoid open water, pressure ridges and rough country meant that we travelled nearly twice that distance. It took us nine days, and in all that time we saw no sign of humanity except for a hunter’s igloo on the last day. In fact, the only life we saw was a lone Arctic owl and two snow partridge.

But during my time with Oodlat I learned from him the things crucial to survival in the high Arctic in winter: how to start the machine when it was minus 40 or less, navigation by the sun, negotiating pressure ridges (ice ridges created by colliding ice sheets), tying and repairing the sledge and many other things . .. including patience.

Inuit have the word “immaaqa,” which has something of the meaning of Que sera, sera. It means that a thing might happen if nature allows it to happen. “There might be seals in this area,” or “We might get through these pressure ridges.”

Patience comes from the kind of life these people have had to live—poised always on the edge of survival. In the old days, a hunter might have crouched over a seal hole for three days, and then had one chance to harpoon the seal as it surfaced. Like the wolves who tracked musk ox over hundreds of miles of tundra, these people learned to adapt to the conditions, rather than fighting to overcome them.

Fighting was more my style. If men or machines hold me up, I get angry. To reach goals, I push myself and take risks. The tighter the deadline, the bigger the risks. Oodlat showed me that in the Arctic that kind of thinking is about as sensible as playing Russian roulette with a full chamber. In this territory, if you carelessly lose so much as a glove you’re risking death.

We reached Spence Bay with less than half a gallon of fuel left in the tank.From there, I had been on my own. It had been scary and exhilarating, but I was quietly proud of myself for having navigated well and found my way through some daunting pressure ridges, one of which was a gruesome mini-mountain range 30 kilometres wide.

As I lay back in the quadriplegic walrus position inside my tent, thoroughly exhausted, I indulged myself in the thought that it had been quite an incredible journey.

[Chapter-Break]

When i awoke at 6.15 the next morning, it was already light. I struggled partially out of my ice-rimmed cocoon and reached for the thermometer. The temperature was the coldest yet: 43 degrees below zero. I made a quick breakfast of tea and noodles, then crawled out to face the day.

“Morning Puke! Morning Ko!” I said cheerily to the machine and sledge, both of whom I addressed as living companions. I had called them Puke and Ko after the New Zealand swamphen, the pukeko, which also had a big reddish nose. Puke had taken on a heroic and friendly persona while Ko was the recalcitrant one of the team who seemed to be always embarrassing or hurting me.

My first job in the morning was to check Puke’s spark plugs. I then flipped the machine on to its side and began to heat the cylinder heads with the stove. This took 30 minutes. With the heads hot, the motor usually fired on the second pull of the starting rope. I ran the engine for a few minutes, then drove around the tent a few times to free up the drive belts and track.

I had rigged Puke up with a simple foot throttle Normally the throttle is operated with the right thumb, but earlier in the trip my thumb had been frostbitten, and working the lever aggravated the injury. By attaching a length of cord to the throttle lever, passing it over the bar and tying a loop in the other end, I could successfully operate the throttle with my foot.

The final task each morning was to load Ko, and because the sledge was narrow and tipped easily it was important to get the heavy stuff as low as possible. The last items to be lashed on were the things I might need in a hurry, in particular the tent and the gun.

Navigation in the Arctic is never easy, particularly when travelling on sea ice out of sight of land. In the Northwest Passage it is further complicated by the close proximity of the Magnetic Pole, which makes a compass difficult to use. Although I carried a global positioning system (GPS) it was too cold to use it in the open. The liquid crystal read-out would normally freeze before the GPS had picked up sufficient satellites to make a fix. Mostly I relied on the sun to navigate by. So long as I maintained the current time and adjusted my watch one hour for every 15 degrees of longitude, the sun made a perfectly adequate compass. At 6.00 A.M. it was due east, so my shadow pointed west like a directing finger. At midday it was due south, so to maintain my westward heading I just needed to keep my shadow pointing north. But initially I had no faith in my ability to navigate in this way, and often I would have to force back rising panic if the sun appeared to be in the wrong place.

On April 16 I entered a bay with a small village at one end. It was an unusual place in that the houses were clustered in three areas, rather than just one as was normally the case. I wasn’t sure which houses to go to, and was feeling shy. I drove past the first group, peering towards them in the hope of seeing some life. There was none, so I headed towards the next lot. Then I saw a person at the third cluster. I drove off the sea ice and up the hill, but I miscalculated the steepness of the slope and stalled awkwardly mid-way up.

As soon as I stopped, snow machines zoomed out from the other houses and arrived all together. “Welcome to Bay Chimo!” shouted the riders. A woman called Gwen, who seemed to be the matriarch, took my hand and joked, “Funny place to park!” then, without asking him, added, “You can stay with John.”

Bay Chimo (Umingmaktok in Inuit) was the most basic place I have ever been to. There was no running water, no electricity, no phones, no TV, no cop, no nurse but the people seemed very happy.

It was snowing lightly next morning when Gwen took me to the mouth of the bay and pointed across the white nothingness in the direction of Coppermine, 350 km to the west. “Go more right than left,” she said. I looked at her curiously. She read my face. “You’ll know what I mean when you get out there,” she said, waving her arm at the empty horizon. “And good luck,” she shouted as I revved Puke and headed out. I hoped that this would be the last time I’d be out of sight of land—it always made me nervous.

Gwen had been right. When I got out there I found myself mysteriously drawn to the left, and began to doubt the sun. Perhaps it was the land exerting some mysterious pull on me. I don’t know, but I felt disorientated. After an hour I saw a black dot to the northwest about two kilometers away, then another to its left. I headed towards them, but when I was a few hundred metres from the objects they disappeared. They must have been bearded seals that keep their holes open through the sea ice all winter long.

[Chapter-Break]

Over the next week I passed the villages of Copper mine and Paulatuk. With spring imminent I began the scary race with the ice break-up. The most arduous section of the journey was now behind me. All I had to do was to drive north for 80 km until I could get around the Smoking Hills, west for 100 km across the neck of land to Liverpool Bay and then a few hundred kilometers southwest to Tuktoyaktuk. However, fate had something else in store.

Accidents often happen when you least expect them, and so it was in this case. I was bumping my way over an area of broken sea ice. To my left clouds of smoke rose incongruously into the steely Arctic grayness from the naturally burning sulphur of the Smoking Hills. To my right and ahead the frozen sea went on forever until it merged with the sky.

Suddenly my snow machine’s left ski dropped into a crack in the sea ice. The machine lurched to the right and I went left. For a short time I desperately tried to stay in contact with the machine but it was hopeless and I crashed in an untidy heap on the ice Unfortunately, my right boot was still hooked into the foot throttle, so rather than stop, which would be the normal case when you fell off, the extra tension on the cord made the machine accelerate, and I was dragged like a rag doll across the rough ice. I kicked frantically to free my foot, and when it was released I had a split second of relief followed by a moment of dread as I realised I was about to be run over by the half-tonne sledge which was barreling along with undiminished momentum across the ice.

Fear gave way to pain as the steel-tipped right runner struck my hip, projecting me from zero to 40 km in an instant. I thought my pelvis must be smashed, but I knew worse was to come if the sledge went over me. My legs kicked wildly and I pushed with both hands on the front cross member as the out-of-control monstrosity drove me ahead. It was like a fight to the death with a wild animal.

Finally we stopped sliding, but my right leg was twisted at a grotesque angle, trapped beneath the left runner. I was sure it was broken as the intense pain gave way to the numbness that often accompanies a serious injury.

My initial feeling was one of self-pity, and I began to whimper pathetically. What a stupid way to die. Pinned to the ice by my own sledge. I made a feeble effort to push the sledge backwards, but it seemed to be stuck and didn’t move a millimeter. I lay back panting and feeling desperate.Nearby, Puke’s engine seemed to be making so much noise I couldn’t think. “Shut up, for Christ’s sake,” I shouted at it.

The spark of anger gave me some fight. I grasped the front cross member and pushed with all my strength. It cut my leg as it moved half a meter. I flopped back on to the ice, groaning with the pain and breathing heavily.

After a few minutes I made another supreme effort, and this time my leg came free. I crawled across to the machine and hit the kill switch. The world was silent except for my rasping breath. Before long I began to feel sick from shock and I put my head on to the ice. After the first wave of dizziness and nausea had passed, I pulled myself up on the machine and gradually put my weight on to my hip and leg. Neither was broken; at worst I would have some fantastic bruises.

With a feeling of incredible good fortune verging on euphoria, I started the machine and continued northwards. As the Smoking Hills passed slowly to my left I became increasingly aware that the accident had been a crucial incident in the catharsis I’d been searching for. I’d cheated death before, but this time the combination of severe pain, solitude and the calling on some inner reserve of strength had tipped me over the edge into a new state of consciousness. I sensed that I would never be the same again.

I was too sore to enjoy my camp that night. The heavy work of unloading the sledge was painful, and I couldn’t sleep on my left side because of the swelling. But the next day, after covering 225 km, I set up camp in the bright evening sun feeling totally contented. There was a fresh spring quality to the light, and even though the temperature was minus 16 degrees, in the still air it felt quite balmy. I knew that this was probably my last camp alone, and it couldn’t have been better. The low sun shone from a clear pale blue sky which faded to a rosy Arctic gold near the immense horizon, and the ice all around glowed with a quality that was almost friendly. I felt strong and confident, and every bad experience of this seemingly endless journey simply evaporated into space.

Next day I reached Tuktoyaktuk, then continued up the MacKenzie River to Inuvik. I hadn’t completed the section a moment too soon. The ice road was closed by flooding and in places I had to coax Puke and Ko through deep water.

Spring is an exciting time in the Arctic. Higher temperatures quickly melt the snows. The rivers swell beneath their frozen surfaces until the pressure bursts the ice and sweeps it downstream.

The people of Dawson run a sweepstake on when the Yukon River ice will break. In 1993 it happened at 5.30 A.M. on May 1. At that moment the enthusiasm of spring was drawing me south along the Dempster Highway while my partner Jo-anne Wilkinson, who had flown out from New Zealand to join me on the last leg of the journey, awaited my arrival in Dawson.

Compared with what had gone before, our journey down the great ochre Yukon by inflatable was sheer bliss. A companion, warmer weather, a 2000 km winding liquid highway passing through gentle hills and conifer forests, the lingering feeling of being somehow “born again”—these were happy days, though not entirely without incident.

The golden silt-laden waters of this powerful river were deceptively shallow in places, and to our chagrin we sometimes ran aground. Re floating was usually only achieved after much lifting, pushing and grunting, accompanied by Kiwi refloating mantras that usually referred to the illegitimate lineage of the boat.

From an ecological viewpoint, I had felt that Arctic Canada was well managed, but about Alaska I wasn’t so sure. It seemed to be populated by independent-minded hunters, fishers and prospectors who were constantly out of step with the authorities. We often heard locals bemoaning inappropriate laws made in “the lower 48.”

As we made our way down the river, so did a controversy about the culling of wolves. Although these shy creatures seemed rare, they were being blamed for killing too many moose and caribou. The locals seemed evenly split on the issue, but government-sanctioned culling had begun. We were told that the Governor of Alaska, speaking in support of the killing, had made the curious statement, “Well, hell, you just can’t let nature run wild!” This seemed to sum up the ecological management of Alaska.

The river villages ticked past like animated milestones: Tanana, Galena, Ruby, Kaltag, Holy Cross, Russian Mission, Marshall—places left behind by the Alaskan gold rushes, where the gardens surrounding rustic log cabins now sprout old snow machines and outboard motors, and the inhabitants observe the outside world through their television screens.

We entered the sea via the northern river mouth near a village called Kotlik and began the voyage north to Wales and our last hurdle: Bering Strait. Conditions in Norton Sound and that wild coastline the westernmost land on the American continent—were often rough, and our little open boat seemed pathetically inadequate. Sheltered bays were scarce, and the inflatable, with its twin motors and huge fuel tank, was just too heavy to drag up the rocky beaches. So we were forced to make long dashes between the few estuaries.

On June 17, I phoned the Nome weather office from Wales and was warned against crossing Bering Strait that day. The prediction was “9 foot seas and 30 knot winds.” I sought local advice, and was told “the Eskimos say that when the land looks low and indistinct that’s a good sign. If it is high and sharp, stay at home.”

I looked across at Siberia, only 100 kilometers away, and decided the land looked low and indistinct. “Let’s do it,” I said to Jo-Anne and our friend Cynthia Leonard, who had joined us from New Zealand for the crossing—not telling them about the official forecast.

As far as the weather went, it couldn’t have been better, but we were only a short distance into the crossing when we discovered that our boat had a bad air leak. To return for repairs might have been the prudent thing to do, but they say luck favors the bold, so while I drove Jo-anne pumped … and pumped .. . and pumped .. . and Bering Strait passed into memory.

At Cape Dezhnev there was no sign of the Russian border guards, no one to check our hard-won visas, just a few weather-beaten gulls rising on the breeze above the cliffs.The journey was over.