Abel Tasman

The search for Terra Australis Incognita and the discovery of Zeelandia Novia.

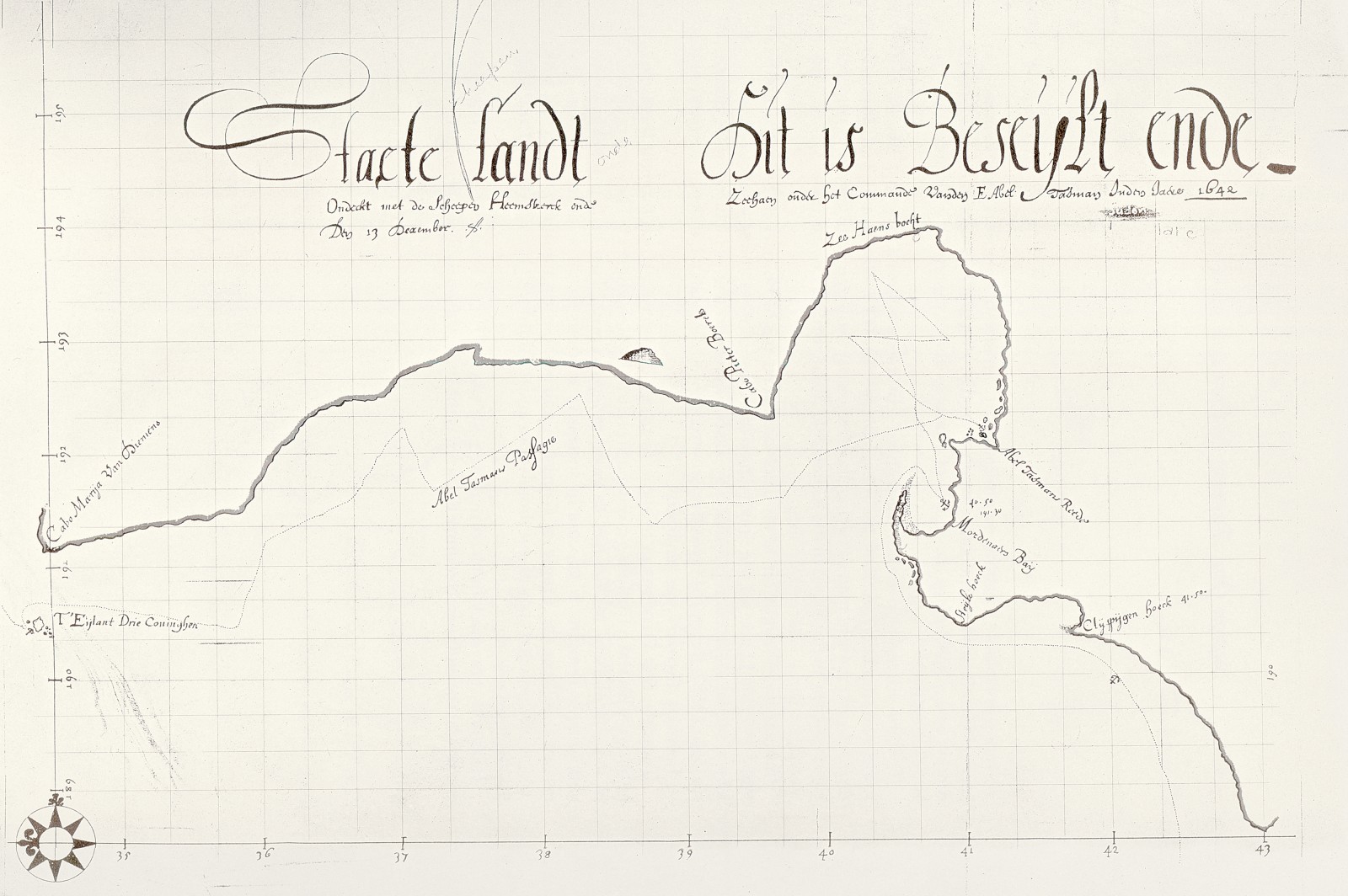

From the lively, undulating deck of his jacht Heemskerck, Abel Janszoon Tasman eyed the mountains land that rose up before him tantalising and indistinct to the south-east. Undoubtedly was the western extremity of Staaten Land—the fabled southern continent whose eastern most tip was first glimpsed beyond Patagonia by Dutch explorer Jacob le Maire a quarter earlier.

Four months out from her home port of Batavia in the Dutch East Indies, Heemskerck had made good speed since quitting the coast of Van Diemen’s Land eight days earlier. A sharp breeze off the starboard quarter filled the jacht’s topsails and, under Tasman’s feet, the long swell rolling up from the south-west seemed proof that no land was to be found in that direction.

Tasman ordered a course change to the south-east, watching the jacht’s prow swing toward the newly discovered peaks on the horizon. It was nearing noon on 13 December in the year 1642. To the best of their reckoning, they had reached longitude 188º 28´E.*

Heemskerck’s steersman watched the last grains of ironsand run through his glass, then reversed it and struck the hour for the afternoon watch. Tasman had a white flag run up and a gun fired, summoning officers from the smaller shadowing fluyt Zeehaen to a council.

Soon Zeehaen’s skipper Gerrit Zanszoon and Isaac Gilsemans, merchant, were aboard and in conference with Tasman, his skipper and second-in-command Ide T’Jerckszoon Holman, pilot major Francoijs Jacobszoon Visscher, under merchant Abraham Coomans and a handful of others.

The council—11 men in all—erred on the side of caution. All were in favour of making for the new land with all speed but, it being a lee shore, they determined not to attempt a landing unless they happened upon a sheltering bay.

By the afternoon of the following day they had closed to within two Dutch miles (13 km) of the land, though thick cloud obscured its peaks.

Tasman wrote in his journal:

We shaped our course northerly and so close in that we could see the surf breaking on the shore…. In the middle of the afternoon we sounded in 25 fathoms—sticky, sandy ground. We sailed along quietly the whole night, the current setting in from the W.N.W. We neared the land till within 28 fathoms—good anchor ground—it still being calm; and, not to go nearer the land, we anchored in the day-watch [between 4 a.m. and 8 a.m.] with a stream anchor, and waited for the land wind.

It was the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the New World by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus. Now, a hemisphere away, Tasman had discovered another landmass.

For the second time since leaving Batavia, Dutch iron had come to rest in uncharted waters. The first had been south of New Holland [not named Australia until 1817] at a place they christened Van Diemen’s Land—now Tasmania—discovered by the expedition and named for Tasman’s “illustrious master”, the governor-general at Batavia, Anthony van Diemen.

Tasman had anchored there at the beginning of December, sending his navigator Visscher ashore in a pinnace with 10 men to explore the land and to see what might be got in the way of refreshments. Visscher had gathered vegetables and found water in a shallow stream. He discovered the land to be cloaked in fine timber and vegetation “not cultivated, but growing by the will of God”.

The landing party heard what they took to be human sounds and came upon two enormous trees with notches cut into their trunks one-and-a-half metres apart—as if made by hunter-gatherers climbing after bird’s nests.

“So there can be no doubt there must be men here of extraordinary stature,” wrote Tasman, who did not himself venture ashore.

A landing was made on the other side of the bay the following day, then the Dutch ships pushed further up the coast of Van Diemen’s Land until unfavourable winds caused Tasman to break off and resume his eastward course.

The second landfall, two thousand kilometres away on the other side of what later mariners would call the Tasman Sea, marked the beginning of a hesitant and strongly criticised exploration of Staaten Land—one that resulted in cartographical error and bloodshed. It was to besmirch Tasman’s reputation and shake the confidence his superiors had placed in him.

The blame wasn’t entirely Tasman’s. He was a product of the world’s greatest maritime machine and its commercial imperatives, and heir to a cumbrous and primitive voyaging technology that was strained to its limits in the service of exploration. In large measure, his failures were the failures of that technology, his successes the triumphs of his people.

The rise of the Dutch had been one of the spectacular geopolitical developments of the sixteenth century. The United Netherlands (modern Holland) challenged the declining power of Catholic Spain and Portugal, weakening the Portuguese grip on distant parts of the globe, including the Moluccas, Java, Borneo, Sumatra, the Celebes and Formosa, which were more vulnerable than Spain’s colonies in the Americas.

The Spanish conquistadors had sought gold and silver for its own sake (Columbus himself once declared that gold could make a person “jump into Heaven”), vanquishing native peoples and laying claim to vast new lands in pursuit of it. However, the Dutch—and their Protestant brethren the English—liked to think of themselves as something new in the world: enlightened merchant adventurers whose interests lay entirely in trade—that new “golden ball”—and who eschewed the mailed fist of conquest in favour of the velvet glove of commerce. The early Dutch and English settlements in Asia were not colonies, therefore, but “factories” or trading stations.

Liberal enlightenment had its limits, however. European realists understood that power was still the goal, even if the means of achieving it had shifted. The new emphasis on trade made control of the world’s oceans vital. This became clear at last even to England’s own “conquistador”, Sir Walter Raleigh, whose obsession with finding the mythical El Dorado was to cost him his life.

“Whosoever commands the Sea commands the trade,” Raleigh wrote. “Whosoever commands the trade of the world, commands the riches of the world and consequently the world itself.”

By the fourth decade of the seventeenth century the world’s riches were largely in the hands of the Dutch who had become the world’s pre-eminent maritime nation. Thanks to the growing dominance of the Dutch East India Company (or VOC—Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie)—a state-sponsored amalgam of independent merchants—they were also the most powerful Europeans in Asia.

Founded in 1602, the VOC was a surrogate government agency to control trade and prices and enjoyed a commercial monopoly in the East Indies (though it was not to achieve a stranglehold in the archipelago until well after Tasman’s voyage). The company’s charter gave it wide-ranging powers including the ability to negotiate treaties and operate fortresses. It was also granted a monopoly on navigation to the Indies via the Cape of Good Hope and, later, also by the Strait of Magellan and the Pacific Ocean. (Indeed it was in an attempt to subvert the company’s monopoly by finding a more southerly route that Le Maire chanced upon what he took to be the tip of Magellan’s Terra Australis, and which he named Staaten Land for the Government of the Dutch Republic.)

More than 60 Dutch ships had reached the Indies before 1602, but it was the founding of the VOC, centred on the citadel of Batavia and with a growing network of forts and trading posts throughout the region, that gave impetus to Dutch supremacy. Controlled ultimately from the Netherlands by a Council of 17 members—the Heeren Zeventien—it grew wealthy through a trade in cotton, spices, silk and precious metals which stretched from Japan in the north to Java in the south.

The scale of profit possible from trade with the Orient had long been evident. The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama had sounded the possibilities in 1497 when his four small ships burst into the Indian Ocean in search of “Christians and spices” and laden with a bizarre collection of tawdry trade goods that included hawk’s bells and brass chamber pots. A few years later a fellow Portuguese in the service of Spain, Ferdinand Magellan—the man who named the Pacific Ocean—set sail with five ships for the Spice Islands (the Moluccas, between Sulawesi and Irian Jaya) which were rich in cloves, mace and nutmeg.

Magellan was killed in the Philippines and one by one his vessels were lost, but when in September 1522 the surviving Victoria limped into Seville with just 21 men aboard, the spices in her hold more than covered the cost of the entire three-year voyage and the loss of four ships.

The VOC’s business arrangements had evolved into a complex system of trade by the time Tasman joined the company in 1632. Europe produced little that Asia wanted so ships tended to carry silver from Northern hemisphere ports and return with sugar, spices and cloth. The poor balance of trade—made worse by the cost of maintaining the company’s presence in the East and of marketing goods in Europe—was largely alleviated by revenue earned within Asia. The Dutch carried sugar to Persia, for example, and used the profits to buy cinnamon in southern India. The VOC also actively investigated every possible source of silver in the Far East with a view to stemming the drain on its coffers in the Netherlands.

Tasman cut his teeth on the local trade. An uneducated sailor from the poor north-east of the Dutch Republic, he learned navigation and seamanship on the job, being appointed skipper of Mocha in 1634 when, as part of a fleet under the command of Frans Valck, he sailed on a two-year voyage to the Moluccas. In the course of routine survey work, Mocha became separated from the other ships and when Tasman went ashore to find wood for repairs a fight broke out. Two of Tasman’s men were killed by villagers and several wounded.

The local company governor showed little sympathy, criticising Mocha’s crew for carelessness and overconfidence while ashore. After a brief sojourn in the Netherlands, Tasman returned to the Far East with his wife Jannetje in 1638, arriving at Batavia after a 180-day voyage. Having renewed his Company contract, this time for 10 years, Tasman embarked on a series of routine voyages in Eastern waters before being ordered on a tempting new assignment.

Several years earlier Willem Verstegen, a VOC official in Japan, had suggested that Batavia despatch vessels to search for “certain rich auriferous and argentiferous islands situated in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean”, said to be no more than 400 miles east of Japan.

The Heeren Zeventien, as ever, thought the pursuit of precious metals a good idea. A source of gold and silver, such as the Spanish controlled in Latin America, would go far to relieving the Dutch trade imbalance. They therefore instructed their councillors at Batavia to fit out ships and to employ “such persons as are intelligent and eager to make important discoveries, besides well-seen in navigation, in making soundings and in determining the exact height, longitude and latitude of such places as they shall call at, and finally skilful in drawing up proper maps of the same”.

The pragmatic VOC was keen on voyages of exploration for practical reasons: to improve the efficiency of shipping goods by finding shorter routes, to discover new trading opportunities and to forestall rivals. The Heeren Zeventien’s emphasis on accurate surveying and mapmaking was understandable. What good was the discovery of valuable new territory if, amid the vastness of the sea, it could not be found again?

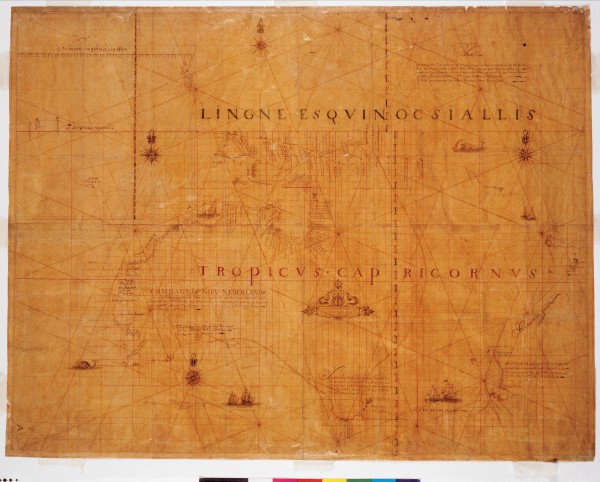

In an age where the considerable blanks on maps were decorated with whimsical sea monsters and loxodromes—compass lines that radiated in starbursts across the uncharted oceans—the thirst for geographical knowledge was keen.

[Chapter break]

As befitted their maritime dominance, the Dutch were pre-eminent mapmakers. Seventeenth century Amsterdam alone was home to a half dozen schools that specialised in cartography and navigation. Surrounded by celestial and terrestrial globes, quadrants, almanacs, compass rectifiers, parallel rulers, Jacob’s staffs and the other assorted instruments of their trade, the company’s mapmakers crafted detailed hand-drawn charts—which were less likely than printed ones to become widely available and to divulge their secrets to the prying eyes of competitors. In the interests of security, ships’ officers signed for all the charts issued to them for their outward bound voyages and were obliged on their return to hand back the same, in their protective metal containers, or face punitive fines.

Officers were also obliged to hand over to the company mapmakers copies of their logs, journals and coastal sketches and to report any geographical discoveries so that the new knowledge could be incorporated into future charts.

[chapter break]

It was against this background in 1639 that Tasman was instructed to take command of a fluyt as part of an expedition by a senior company skipper, Mathijs Quast, in search of two islands called by the Spanish Rica de Oro (Rich in Gold) and Rica de Plata which were rumoured to lie somewhere east of Japan.

The voyage was not a success. After more than five months at sea and with 41 of their 90 crew and soldiers dead the two ships reached Formosa, having achieved little other than locating some insignificant islands north of the Philippines and laying the groundwork for a handsome chart much ornamented with loxodromes.

Tasman’s star was nevertheless in the ascendency. Recognising him to be a “painstaking, helpful and highly experienced skipper”, the VOC soon put him in charge of a trading fleet that was to spend the best part of 18 months in North East Asia, returning to Batavia in late 1641. On the homeward journey, Tasman encountered a severe storm in which the two ships accompanying him were lost. It is a reflection of his growing seamanship that, despite having an unsound and leaky ship himself, Tasman made port. The VOC must have thought so too: on his return they increased his pay from 60 to 80 guilders a month.

He was soon to put himself forward for more important work.

[Chapter break]

In January 1642 Francoijs Visscher, an experienced company navigator, set before the Batavia council a memorandum outlining a proposed exploration of the Southland. It may be the Visscher concocted—or at least refined—the plan with Tasman and the cartographer and clerk Isaac Gilsemans in 1640 while the three were in Japan together on Company business. The seed of the idea may even have been sown by the Governor-General, Anthony van Diemen, who was an enthusiastic supporter of voyages of discovery.

By 1642 Japan’s growing resistance to European activities on its soil made the logistics of mounting further explorations to the east of that country problematic. A voyage in the high southern latitudes was the obvious alternative. If successful, it would result in the discovery of a workable route to Chile and, hopefully, new sources of precious metals. Fortuitously, just weeks before Visscher’s memorandum, an accord with the Portuguese which ended hostilities in the East Indies freed company ships from naval duties and made them available for exploration.

Visscher had suggested several more or less impracticable routes linking the Dutch East Indies with the New World, including one that involved starting at Brazil, heading south as far as Staaten Land then following its coast westward before reaching Batavia via the Solomon Islands.

The course eventually agreed on, however, began on the other side of the globe, in the Indian Ocean. Tasman, by now one of the Company’s most experienced skippers, was chosen to lead the expedition and given two ships for the purpose: the 120-tonne jacht Heemskerck (60 men) and the smaller fluyt Zeehaen (50 men). His instructions were to make for the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, then head south to latitude 52–54ºS where the strong westerly winds would enable him to travel east to the meridian of the Solomon Islands. There he was to turn north and sail home to Batavia via New Guinea and the Moluccas.

By sailing well below the known coast of southern Australia and following the path of the west wind, Visscher and his backers hoped to maximise the chance of finding an unimpeded passage east. This had not proved possible further north where the prevailing currents and airflows hindered eastward exploration along the northern coast of New Guinea.

Tasman was cautioned to exercise care in dealing with the indigenous peoples of the Southland who were “rough” and “wild”—though how Justus Schouten, who drew up the instructions, came to know that is unclear unless he inferred as much from reports of the Aborigines of New Holland.

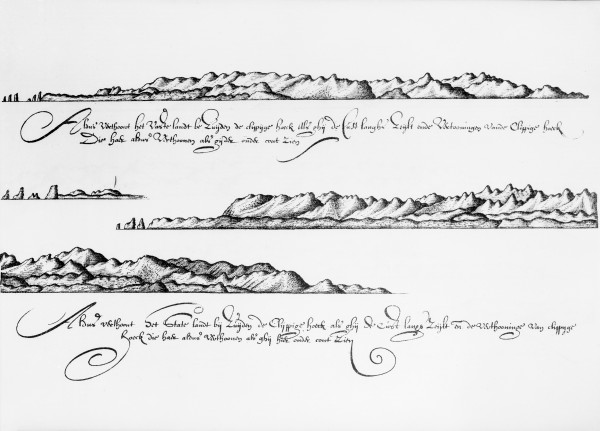

of Farewell Spit as seen from the sea.

If he encountered civilised races, Tasman was to take more account of them, “observing what they esteem and to what goods they are most attracted, particularly finding out what wares are among them, likewise about gold and silver… representing yourself to be not eager for it in order to keep them unaware of the value of the same”.

Thus, along with a modest cargo of European trade goods, Tasman was to convey to the new lands the duplicity of the company. Schouten let it be known that the company expected to be recompensed with “certain fruits of gain” for the outlay and trouble attendant on fitting out such an expedition. In particular, he mentioned the possibility of rich mines, as the gold and silver rich provinces of Peru, Chile…”.

Tasman and his expedition council, finally, were admonished to exercise patience, courage and good management, “so that on your return you will aim to answer before us, to satisfaction”.

[Chapter break]

Heemskerck and Zeehaen reached the Dutch provisioning base at Mauritius on September 5, 1642, having left the roadstead at Batavia on August 14. After much delay and with sufficient supplies to last 12 months, Tasman sailed south, encountering poor visibility and a gale-force westerly which forced a more easterly course. By November 6 the ships had penetrated to 49°S and the next day pilot major Visscher advised following the 44th parallel rather than the 54th specified in Tasman’s sailing instructions.

Consulting the expedition’s inaccurate Portuguese charts, Visscher also calculated that they should continue to 150ºE before heading north to the Solomon Islands. The charts put the Solomon Islands some 18º east of their true location. As it was, the 44th parallel put him on a collision course with Van Diemen’s Land.

Despite their devotion to cartographic accuracy the Dutch, like all seventeenth century seafarers, were compromised by primitive navigational technology. The sun’s altitude and the relative position of the heavenly bodies—used to determine latitude—were calculated using astrolabes, cross staffs and astronomical tables. Even the simple log, for measuring a ship’s speed through the water, was a recent introduction. Longitude was to remain a problem until the advent of accurate chronometers more than a century later: plotting position to within 100 kilometres required a timepiece that gained or lost less than 60 seconds a month, whereas the watches available to Tasman typically lost a quarter of an hour a day. Tasman made do with sandglasses and dead reckoning.

Having made landfall in Van Diemen’s Land on November 24, they spent just a few days in coastal waters before pressing eastward.

By mid-December they had closed to the west coast of Staaten Land (between Hokitika and Okarito), which they then followed north. At sunrise on the 17th smoke was seen rising from the shore—probably from a Ngati Tumatakokiri kainga near Taumauku (Cape Farewell). The next evening, having rounded Farewell Spit, the ships anchored off Taupo Point in 15 fathoms of water.

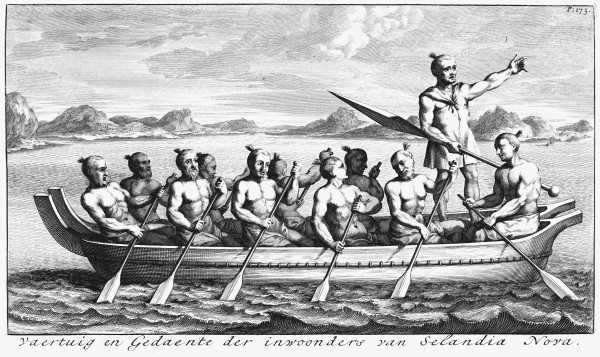

That evening they saw lights on shore and made out two waka paddling toward them. At the same time two ships’ boats which had been despatched to look for fresh water and a better anchorage returned to the Dutch vessels.

“About one glass after [our men] had returned on board the people in the two prows began to call to us, and that with a coarse rough voice, but we could not understand in the least what they said,” recorded Tasman.

There followed a bizarre exchange as Maori repeatedly sounded an instrument “like a Moorish trumpet”—possibly to see off what they took to be unknown spirits—and in an effort to establish a rapport with those in the wakas trumpeters aboard Heemskerck and Zeehaen replied. As darkness fell the Maori left off and retired to the shore while Tasman took the precaution of ordering watches to be set and “the munitions of war”—muskets, pikes and cutlasses—got ready.

The groundwork for tragedy having been set, the encounter was taken up again the next morning when a waka appeared near the anchored ships. Tasman displayed linen and knives in an attempt to lure the Maori aboard but they returned to shore. Zeehaen’s officers then boarded Heemskerck for a prearranged Council where it was decided to anchor closer to shore “as these people (as it seemed) sought our friendship”.

[Chapter break]

Soon Seven more waka appeared, at which Zeehaen’s skipper ordered his quartermaster back to his own vessel to limit the number of Maori allowed aboard. Suddenly, one waka rammedn and attacked the quartermaster’s small boat. Three of its crew were killed, and a fourth mortally injured. The stunned Dutchmen fired cannon and small arms at the retiring Maori—who took one of the bodies—but did not hit them.

Tasman, a man who in his career had shown himself not averse to dispensing rough justice on behalf of the Company, stayed his anger. Perhaps the words of the expedition’s trade-minded sponsors came to mind: “You will prudently prevent all manner of insolence and all arbitrary action on the part of our men against the nations discovered, and take due care that no injury be done them in their houses, gardens, vessels or their property, their wives, etc…”. The small boat and all but one of its crew were recovered and, having weighed anchor, the Dutch sailors fired volleys at upwards of a dozen newly approaching canoes before steering east north east in search of fresh water.

The place of the attack they named Murderers’ Bay.

Bad weather dogged them as they attempted to sail north, forcing them to ride at anchor in the lee of what is now D’Urville Island until December 26. Having celebrated Christmas Day with wine and meat from freshly slaughtered pigs they continued north, discovering a passage (Cook Strait) that unfavourable wind prevented them from entering. Curiously, Tasman omitted the passage from his later report and chart—though he had deduced its existence from a strong current—whereas Visscher clearly indicated it on his own chart.

By January 4, 1644, they were off a cape that marked the northernmost extremity of Staaten Land which Tasman named after Maria, the wife of their governor-general. Again the weather prevented Tasman from rounding the land to eastward, and when islands were sighted to the north (which Tasman later named The Three Kings for the Christian feast day eve on which he anchored there), they closed with them in a renewed attempt to get fresh water—none having been got ashore since leaving Mauritius five months earlier.

The next day boats were lowered and Visscher and Gilsemans went in search of water which they found in plenty cascading over a cliff. Prevented from landing by the surf they rowed along the coast, seeing “30 to 35 persons—men of tall stature, so far as they could see, with staves or clubs” who in walking “took great steps and strides”.

They returned to the ships and next day were again stopped from filling their casks, this time by a strong counter-current and strengthening breeze in addition to the surf. Tasman summoned the Council which resolved to lift the anchors and venture north into the Pacific.

“Near noon we got under sail, leaving the island at noon about three miles [19 kilometres] from us due S.”

Staaten Land had not been kind to Tasman.

[Chapter break]

Neither was the VOC—despite the fact that before returning home Tasman went on to discover Tonga and Fiji. Though Tasman’s superiors at Batavia showed little outward displeasure at the results (perhaps to placate the Heeren Zeventien), they expressed regret at his hasty and superfacial exploration which left the accurate tracing of coastlines and the searching out of trade opportunities “be executed by a more inquisitive successor…”.

As it was, despite indications from the voyage that a sea route to Chile existed—which, after all, was a prime goal of the voyage—hostilities had once again flared with the Portuguese and no ships could be spared for further investigation.

And, at the very time that Tasman had been fending off bellicose Maori, a former Governor-General of Batavia, Hendrik Brouwer, had taken five ships around South America on behalf of the Dutch West India Company. While the main fleet made for gold-rich Chile one vessel lingered to examine Le Maire’s Staaten Land in greater detail. It was found to be merely a small island. Tasman’s theory of the possible connection between his newly sighted land and Le Maire’s Staaten Land was unravelling even as he pondered it.

Just two years after his voyage, the VOC’s Amsterdam Chamber issued a map showing Australia as New Holland and, for the first time, naming Staaten Land “New Zealand”—both names deriving from provinces in the Netherlands where the VOC had chambers.

In 1644 Tasman’s rank of skipper commander was confirmed and he and Visscher were despatched to discover whether a channel existed between New Guinea and Australia and to explore more of the Australian coast. Although they traced the southern fringes of New Guinea and northern Australia from today’s Cape York to Port Hedland, they returned early and again did not venture ashore. The Batavia Council could scarcely conceal its frustration. “What there is in this Southland, whether above or under the earth, continues unknown, since the men have done nothing beyond sailing along the coast; he who makes it his business to find out what the land produces must walk all over it, which these discoverers pretend to have been out of their power…”.

Worse was to come. In 1648 Tasman led an unsuccessful attempt by eight vessels to capture a Spanish silver ship in the Philippines and was accused of attempting, while drunk, to hang two of his men for trivial offences. He was tried and found guilty, stripped of his rank, fined and ordered to pay damages. Eleven months later he was reinstated.

By 1653 he had left the Company, though he remained in the East Indies with his wife and daughter, owning land and a small cargo ship. However, he fell out with the Reformed Church and became something of a social outcast before his death in 1659.

What of Staaten Land? For many years Southland remained a slippery region for European mapmakers. As late as the eighteenth century the east coast and interior of Australia were yet to be explored and many still thought Staaten Land (New Zealand) formed part of an inhabited southern continent—a vast new America ripe for exploitation and colonisation.

The notion was vague and appealing enough to support a whole industry of literary exotic fantasies. Hendrik Smeeks’ The Mighty Kingdom of Krinke Kesmes (1708) was just one of a swelling genre that exploited geographic and ethnographic ignorance. Not until Cook’s arrival in 1769 was an authentic outline of New Zealand fixed to the map.

At this distance it is hard to get a handle on Abel Janszoon Tasman. He was not a particularly conscientious explorer, and some have suspected that both he and Visscher were motivated above all by the lure of gold. However, there is little doubt about Tasman’s experience and seamanship, and crews were willing to repeatedly sail under him. None of his men attempted to mutiny and unusually few of his crews died of scurvy or from other illnesses.

It must also be said that Cook enjoyed enormous advantages over Tasman. For one thing the technology had improved enormously over the intervening century or more. Cook carried with him Harrison’s chronometer, which made calculations of longitude more accurate, and the Hadley octant which replaced the less precise, centuries-old quadrant. And his ship was more seaworthy and manoeuvrable. Nor was Cook handicapped by the Dutch system of collective decision making or the VOC’s overriding commercial objectives. Moreover, he had on board the invaluable Tahitian Tupai as translator.

The American historian Daniel Boorstin once wrote: “The most promising words ever written on the maps of human knowledge are terra incognita—unknown territory”. If Boorstin’s words attach more readily to Cook than to Tasman, the Dutch voyager nevertheless left his mark.

Despite the fact that he was only in local waters for three weeks, Tasman’s name has become wedded to that of New Zealand. Exploration and discovery gave his life a trajectory and perhaps a solidity that it would otherwise have lacked. It carried him the length of this land—if not ashore—and he lived to tell the tale. His spirit may not have been ardent, but it had at least been kindled.