A plague on all our houses

How one bacterium built our health system.

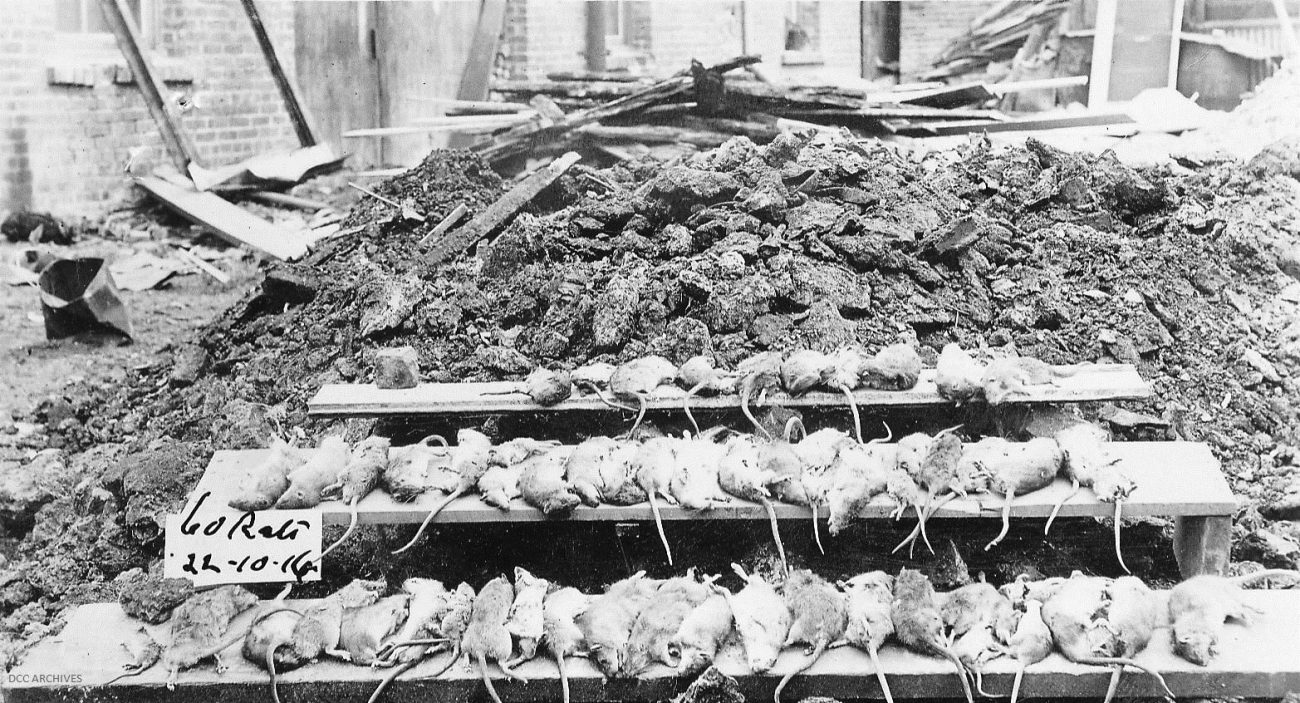

On 19 April, 1900, a sickly rat was discovered crawling in full daylight along the floor of a wharf shed in Auckland. On examination, it was found to have typical signs of bubonic plague infection, including plague-like bacilli in its spleen, liver, and lymph glands. Days later, a second rat was found in a nearby shed, and within a week, six more.

Medieval Europe had been decimated by the Black Death, and evidence of its reappearance in modern times unnerved health officials. For several months, they had watched with increasing unease as a plague pandemic spread from China, where it had resurfaced in 1894, and gained a foothold in Australia. By the middle of April 1900, 116 cases of plague and 40 deaths had been reported in Sydney, and trans-Tasman shipping was in disarray.

Two Government-appointed health commissioners urgently despatched to Auckland. James Mason, a doctor, and bacteriologist John Gilruth, the chief veterinary officer, found much wrong with conditions in the city, including a substandard water supply and haphazard collection and disposal of rubbish. They also inspected and condemned a number of old buildings.

Mason and Gilruth met resistance from business owners who, with an eye to the likely effect on their income, were reluctant to report sightings of infected rodents on their premises. Matters were not helped in May when a boy who had been admitted to hospital with a rat bite was found not to have plague, as officials had loudly asserted. Unsurprisingly, the subsequent discovery of a case of plague in June was greeted by widespread cynicism.

That second case was an Auckland man named Kelly, who had become unwell on June 16. Drowsy and in pain, Kelly soon began to complain of a swollen groin. A doctor who saw him the following day suspected plague, but was reluctant to report it. On June 22, a second doctor was summoned and he agreed with the diagnosis. That night, Kelly died, and a post-mortem examination found what looked to be plague bacilli (Yersinia pestis). The diagnosis was later confirmed by the Paris-based Pasteur Institute, which had been sent a sample. Kelly’s home was disinfected, family members quarantined, and Auckland passengers bound for other ports in New Zealand required to undergo a medical examination on arrival.

Not everyone was convinced, however, and there was talk of a “plague scare”. One medical practitioner attributed Kelly’s death to blood poisoning and offered the opinion that even if bubonic plague had arrived on New Zealand shores, the country’s climate and resistant population rendered it harmless. This was proved, he said, by the fact that none of the 31 known close contacts had become ill. He was perhaps ignorant of the fact that bubonic plague is most commonly spread by fleas. Indeed, the outbreaks on both sides of the Tasman reached their peaks in autumn, called by one investigator “the season of fleas”.

Despite public apathy and pockets of stubborn opposition, the outbreak eventually subsided. Over the next few years, a total of just 21 cases and nine deaths were recorded in New Zealand, the last in 1911. During this period, there were several likely reintroductions of plague, one in 1907, caused by infected rats on a steamer carrying bone dust from India, where plague was then killing some 500,000 people a year.

The arrival of plague had a silver lining: it caused a shake-up in New Zealand’s archaic approach to disease control. The patchwork of ineffective local boards was swept aside by the Public Health Act 1900 and replaced by a forward-looking Department of Public Health, with Mason himself as chief health officer.