“A perfect pack of devils”

How a town called Maxwell got—and lost—its name.

On 27 November, 1868, nine-year-old Ihaka Takarangi set off with a gaggle of other children from Tauranga Ika pā at Nukumaru, near Whanganui. They were at a woolshed three miles from home when Pākehā troopers on horseback appeared and began to fire. The children scattered. Ihaka was shot through the thigh and fell into a flax bush. A trooper slashed at his head. Instinctively, the boy threw up his hands.

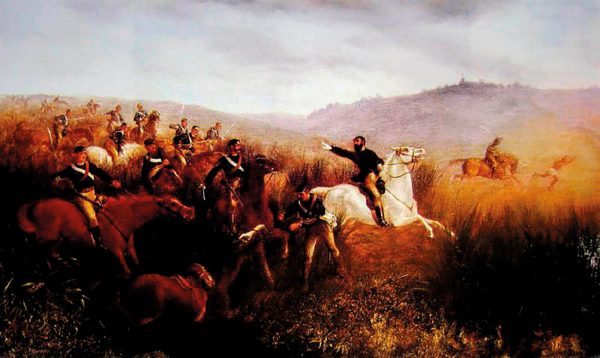

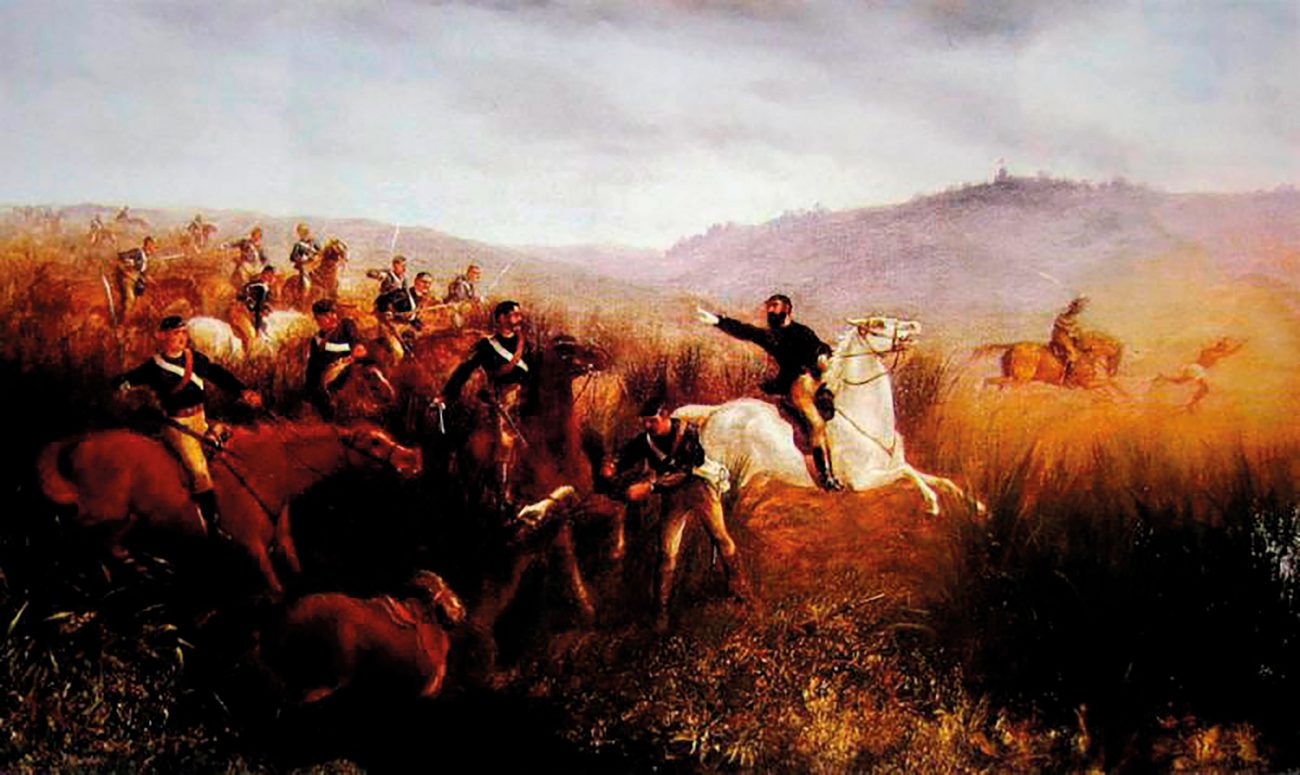

At the time, Ngāti Ruanui prophet and military commander Riwha Tītokowaru was leading resistance to the confiscation of Taranaki Māori lands. War had returned to the troubled region and the Kai Iwi Cavalry, a volunteer settler unit from Whanganui, headed by Lieutenant John Bryce, was formed in October.

The unit quickly gained a reputation for ill-discipline. Even George Whitmore, the overall commander of Crown forces, described them as “a perfect pack of devils, and most uncontrollable”, adding that, “If they smell natives, they follow Bryce like a pack of hounds, and cut, slay, and destroy the poor natives before you have time to look around you.”

Whitmore’s words proved prophetic. The official report of what happened at the woolshed just weeks later noted that the cavalry had killed eight “Hauhaus” (a term initially meaning an adherent of the Pai Mārire faith but later applied more generally to Māori who fought against the Crown) with sabre, revolver and carbine. Sergeant George Maxwell, it added, had “himself sabred two and shot one of the enemy”.

One crucial detail had been omitted from this account. The Māori party that the troopers attacked were not adult fighters but a group of young children, between six and 12 years old, who were out hunting pigs and geese. Bryce’s men did not abandon their assault when they realised their targets were children.

On the contrary, as historian James Belich writes, they “charged in for the kill, not despite the fact that their quarry were unarmed children, but because of it”.

Kingi Takatua, aged about 10, was decapitated by a trooper’s sword. Akuhata Herewini, around 12 years old, died as a result of multiple sword attacks. Others were wounded. Ihaka Takarangi, the boy who fell into the flax, survived but lost several fingers shielding his head.

Maxwell, who played a prominent role in these killings, died weeks later in a nearby skirmish. Two years on, when a settlement was surveyed close to the woolshed, it was named Maxwelltown (and later simply Maxwell) in his memory.

Bryce, later notorious for his role in leading the invasion of Parihaka in November 1881, had been chasing a runaway horse when some of the cavalry began their advance on the children. He eventually caught up with Maxwell and the others and issued orders for them to retire. Maxwell at first refused before eventually complying. Bryce arrived at the scene in time to watch the second gravely wounded boy die. He did not personally take part in the killings but was complicit in the subsequent attempt to cover up the fact that his men had deliberately targeted and killed children.

Not everyone was willing to accept the cavalry’s version of events. In 1883, Australian journalist and historian George Rusden wrote in his three-volume history of New Zealand that “women and young children emerged from a pah to hunt pigs. Lieutenant Bryce and Sergeant Maxwell of the Kai Iwi Cavalry dashed upon them and cut them down gleefully and with ease”. An indignant Bryce sued for libel and the case went all the way to the Privy Council. As there were no women present—only children—and Bryce had not personally “cut down” anyone, the action succeeded. But the case helped expose the gruesome details of the attack.

In 2021, the New Zealand Geographic Board upheld an application from mana whenua Ngāti Maika to change the official but offensive name of Maxwell to Pākaraka, which was the customary name of the area, referring to a settlement surrounded by karaka trees. Like so many other place-name changes around Aotearoa, this was a small but important step in acknowledging an offence and the history behind it.