A feeling for clay

That Earth’s humblest materials can be transformed into sublime and beautiful objects is part of the romance of the potter’s art. But it takes patience and strong hands to work such miracles. Barry Brickell, the doyen of Coromandel potters, has shaped clay dug on his property at Driving Creek for close to 40 ears. His trademark work are tall, sensuously curved sculptures, in which the clay has been laboriously kneaded and pressed into shape without the use of a potter’s wheel. A single piece may take up three weeks to complete.

Lately, I’ve been having trouble with my cactuses. It’s not through lack of attention—they are well used to that! In fact, this is why I keep these evergreen hedgehogs: they are just about the only plants that can tolerate the vicissitudes of the writing profession, the frequent and lengthy absences that leave household flora in a constant state of semi-drought.

I’m fond of my cactuses. You can’t hug them the way some people hug trees, or stroke them as you would a cat, but otherwise they are admirable companions: stoic and dignified in their self-reliance, forgiving yet commanding respect. And when you least expect it, they reward you with an extravagant blossoming. All they need is some earth, a trickle of water and plenty of sunshine, and as these abound in Wanaka, the malaise of my cactuses was disconcerting. What floricultural transgression had I committed?

My friend Jacou Vettard, a petite Frenchwoman who lives by the lake, had once worked in a cactuserie near Cannes, so I sought her advice. My plants were not so much dying, I explained, as comatose, showing no enthusiasm for life. An odd thing for cactuses in the middle of an Otago summer.

She listened attentively, as a doctor or vet might, then gave her opinion: “You need to repot them into something spacious and earthy. Perhaps a terracotta tray.”

I had half expected such a prescription, because if cactuses are Jacou’s hobby, her vocation is pottery. That afternoon she was making ocarinas—bird-shaped flutes which she sells at local markets—and as her work table was stacked high with clay cups, bowls and platters of assorted sizes, I thought she was trying to peddle some of her wares. But no, she didn’t have any trays, and was too busy to make one for me. But did I want to have a go at shaping something, she asked? Perhaps not a tray, but a bowl, for starters.

There was a lump of clay on the table, and she sliced off a piece as if it were a Christmas cake, and showed me how to make a pinch bowl. I worked on my little creation for a while, and Jacou promised to fire it later. It was a crude effort, well within the confines of Primitivism, but making it gave me a feeling of artistic pleasure.

Yet seeing Jacou work, I also became aware of something else. Her pieces were all more or less deformed. She’d turn a perfect pot on the wheel, and then give it a squeeze, a pull or a neck-wrenching twist. These were deliberate imperfections, and the overall effect was pleasing in a nonconformist sort of way. Like faces, songs or sunsets, no two pots were exactly the same.

This individuality is surely one of the attractions of pottery. We live in a world of templates and uniformity, of computerised assembly machines working to tolerances so fine they contradict the meaning of the word. Your china is made near Manchester, and your manchester is made in China. Your shoes are probably made in an anthill factory that itself resembles a machine. In the midst of all this standardisation and amalgamation, pottery offers a refuge of uniqueness for both maker and user. It is handmade and personal—so unmistakably and wonderfully human.

It may also be one of our last bastions against the encroachment of plastic. Less than two decades ago in India, before the subcontinent succumbed to the unbearable lightness—and permanence—of polystyrene, you could buy a sweet tea from a tray of quickly thrown sun-dried clay cups which the raucous vendors milling around train stations carried on their heads. You’d sip this unmistakable taste of the Orient as the train pulled away from the platform, then fling the empty cup out the window and watch it disintegrate on impact with the sun-baked earth. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. Bang! Instant recycling.

Unlike the chemistry of polymeric plastics, the rudiments of pottery are truly elementary. Mix clay with water and knead it like dough, shape into the desired form and leave to dry. Bake in a kiln, perhaps glaze it, then bake again to let the glaze settle. Like making French pastries, really.

If you believe the ancient scribes, God himself was a ceramist: he created Adam and Eve from the dust of the ground. Through the ages, the devout have echoed the prophet Isaiah’s confession: “We are the clay, and thou our potter.” It is a source of wonder that human artists can so readily follow the divine formula: the blending of elements in an act of creation that is limited only by the imagination of the begetter. Clay is a forgiving medium, infinitely pliable, recyclable, responsive—and cheap. You can take seemingly dead earth and breathe life into it, turning it into something shapely and beautiful, something of value, something that lasts.

And pottery has lasted remarkably well, longer than any other artefacts made by the human race. Buildings crumble, iron rusts away, timber rots, paint cracks and fades, paper gives in to the munching mandibles of time. But pottery—chipped and broken though it may be—remains, hard as rock, storing within and on its surface the history of civilisation.

Next to cupped hands, an empty shell, a bamboo tube or a sewn-up animal skin, clay pots are the oldest vessels known to humankind. Crude, soft earthenware found on the Anatolian Plateau in Turkey dates back 9000 years. The rise of Mesopotamia—the “land between the rivers” and the mud-brick cradle of modern civilisation—was well recorded in clay. The birth of the first city, which transmuted hunter-gatherers and nomads into urban folk, coincided with the invention of writing, and pottery was the paper of the earliest chroniclers and literati.

There has hardly been a civilisation that did not excel in pottery—the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans, the Incas and Mayas, the Chinese. Closer to home, the migrations of an entire culture have been traced by its pottery alone. The Lapita people, named after a site in New Caledonia, were highly mobile ocean explorers, and are thought to have been the original settlers of the western Pacific. They spread from Papua New Guinea throughout the islands of Melanesia and parts of Micronesia to Tonga and Samoa, and carried with them an unmistakable style of pottery. Their pots were coiled from clay rolled into thick ropes, dried, wrapped in grass and baked in an open fire; then, while still hot, covered with plant resins for waterproofing, and later decorated in the same pointillist style you can still see in many Polynesian tattoos. The Lapita flourished between 1600 and 500 B.C. Today, only the shards of their pottery remain.

Will we leave behind something equally exciting for the future archaeologists to sift through? Jacou Vettard, for one, was doing her best to see to that. In fact, she was just getting ready to leave on a road tour of New Zealand potteries, a peripatetic apprenticeship during which she wanted to spy a little, learn a little, and try to define her own style. She invited me to join her.

Like many home-grown potters, Jacou has been almost entirely self-taught, learning her craft by watching, emulating, experimenting. Now she was on the verge of taking a leap of faith: to actually make a living out of her passion. This grand tour of the country’s clay-workers was to be her last deep breath before taking the plunge.

For me, it would be a chance to find out how the country’s ceramists were faring. I suspected that all was not well in potting land—considering the amount of dirt-cheap imported terracotta and its plastic lookalikes I observed in the local hardware store. But then again, how many times had I driven past a “Pottery” sign and not turned down that gravel road? Here was an opportunity to redress the neglect.

One morning in early summer we drove north to visit the wizards of earth and fire.

[Chapter break]

Fifteen kilometers north of Kaikoura a sign invites us down an unsealed road towards the ocean, past surfers’ camps, where boards stand propped against trees festooned with drying wetsuits. Near the beach we find the home and studio of Juanita Edelmann, a wiry woman with a mop of curly sun-bleached hair, a confident face and a knuckle-crunching potter’s handshake. A native of Philadelphia and a self-professed sailing bum, she washed up here after a seven-year round-the-world trip, and in 1974 bought this stunning piece of land between the mountains and the sea for a mere $6000.

There wasn’t much work around, she tells us, so after some itinerant fruit-picking she took up pottery, and struck a river of gold: “There was a pottery craze in those days. You could sell anything. In one weekend we sold a thousand dollars worth of pots. That kept us fed for six months.”

With a flood of Asian-made ceramics now coming into the country, the river of gold has shrunk to a trickle, but for Edelmann and her family pottery still keeps food on the table.

“I’m not an artist, not a ‘known’ potter,” she admits, with a hint of defiance. “I don’t make dust catchers. I never get into exhibitions or galleries, and every time I send something out to a competition, it comes back with a comment from the judges like, `The glaze doesn’t suit the form.’ Well, hell, I still turn good pots, and I sell everything I make. When people break a piece they come back to have it replaced. For me, that’s a measure of success.”

Not monetary success, though—not any more. But look around, Edelmann says. An organic garden, a sunny house full of macrocarpa furniture, flax bushes with their red chilli-pepper flowers, muscular surf on one side, the pyramid peaks of the Seaward Kaikouras on the other—what else would you want?

Edelmann’s story, with local variations, would be repeated time and again as I travelled: an idyllic lifestyle paid for by a home-based craft; self-reliant people making unpretentious pottery. You buy a mug, a jug, a jar or a vase, and you take a piece of their life and that place with you. No machine can give you that.

Unexpectedly, on a shelf in Edelmann’s shop I notice a statuesque tail of a breaching whale. A dust catcher? “Yeah.” She waves dismissively. “In Kaikoura you gotta do whales’ tails.”

On the road again, Jacou and I cross the straw-coloured hills of Marlborough, drawn as if by magnet towards the potter’s Mecca that is Nelson and Golden Bay. But before we get there, a craft trail map offers an enticing detour. On a hill rising like an island above the vineyards of the Wairau Plains, Fran MacGuire sits in the living room of her mud-brick house, examining a collection of her new pots.

Some of the pieces carry the colours of Marlborough—yellow, orange and gold—scratched with stick-figure hieroglyphics, but what catches the eye is their extremely fine ornamentation: latticework patterns that give them the look of carved ivory. Jacou fingers a candle holder in disbelief. “This is days of work,” she whispers.

There is something else, too. MacGuire draws inspiration from mechanical forms such as bolts and nuts and pieces of plumbing, and although she’s been potting for only a year, she can now mock mechanical precision with her own handiwork.

One piece in particular seizes my attention. It’s a bloke’s mug, the colour of aged leather, and studded with screws so real you want to poke a screwdriver into them just to see if they turn. I immediately see it in a friend’s shed, steaming with a fresh espresso, surrounded by his scattered tools. How much would a mug like this cost, I inquire? She names the price, and it does not seem exorbitant, not for the amount of work involved. Alas, the piece is not for sale. It’s a breakthrough in MacGuire’s experiments with glazes, and is to be her most hopeful entrant in an upcoming pottery competition. Winning competitions is what matters in today’s art-and-craft market, she explains. It gets your name around, it generates commissions.

But I really want this mug, I tell her. It’s a desire to possess—not greed, more a yearning for a thing of beauty, a feeling which will strike me a few more times on this trip. I call it the Utz syndrome after the compulsive porcelain collector in a Bruce Chatwin novel of the same name.

MacGuire laughs and relents. All right, after the exhibition she will send me the mug. A promise.

[Chapter break]

Eat in Marlborough, but do your art in Nelson,” she tells us in farewell, and indeed, the sunshine coasts of Tasman and Golden Bay have become New Zealand’s equivalent of the “land between the rivers”—a cradle of cottage crafts, with the city of Nelson at its centre.

Pottery studios are as abundant here as vineyards are in Marlborough, and, like the wineries, they have been strung into a handsomely mapped trail stretching all the way to Collingwood. As we travel from studio to studio, two things become apparent: there are an awful lot of potters around, and for many of them business is not exactly brisk. Making a decent living out of clay is no longer a matter of pottering around in your shed when the mood seizes you, but a highly competitive enterprise requiring astute marketing as well as artistic flair.

“You have to stay on your toes, always trying to predict the next trend,” says Corinna Wanty, a young German expat. It helps to keep a few eggs in other baskets, too, and for Alan Ballard, with whom she shares an Appleby studio, this happens to be a creel.

Ballard, a highly regarded fly-fishing guide, leads frequent angling sorties into the Nelson and Kahurangi rivers, though he says he’d rather be potting. He advocates a strict catch-and-release regime, but that doesn’t mean you have to go home empty-handed. You can order a ceramic trophy fish of any species from him. Just be careful approving the size; it will shrink during firing!

Why doesn’t he just go fishing full time? “I did, for about a decade,” he tells me, “but, you know, there is something about the clay, something addictive. After Michelangelo sculpted David, in marble, he said that the form was already there, that he just chipped away the rough edges. Well, with clay, you can take creation a step further. You not only subtract, you also add. In your hands, the clay is alive.”

But if you’re a potter and want to keep yourself alive, and if you don’t fish, or have an orchard or a bed-and-breakfast, then you’d better have a name that opens the gallery and exhibition doors like a battering ram. A name like Darryl Robertson.

One wall of Robertson’s Bronte Peninsula gallery is crowded with laurel certificates and awards of merit. One comes from the exhibition that accompanied the 1992 Seville Expo—Tresoros del Misterioso Mundo Antipodo (haplessly mistranslated as Treasures of the Underworld, as if the antipodes were some kind of Hadean pit). Robertson’s entry—a tetrad of large plates featuring an elaborately painted collage of classic New Zealand images: mountains, surf and whales under the Southern Cross—gained him worldwide recognition as a ceramic artist.

Today his prices and sales reflect this status. What a lovely dinner service at $300 a plate! And coffee mugs, just $70! Each is an adorable chef d’oeuvre; it would be nice to have a set. The Utz syndrome kicks in.

A short distance along the Tasman Bay coastal highway, in Steve Fullmer’s gallery, business is good, too. Cartons by the door are marked for shipment to Japan and Brazil, and inside Fullmer is enthusing to a group of shoppers about the technical nuances of glazes. Now and then, you hear a casual zip-zap of a credit card machine.

Fullmer, built solid like a kiln, is a blond Californian now well rooted in Nelson soil. He used to make terracotta gardenware, he says, but now he can’t even buy clay for what a perfectly acceptable planter costs at a cut-price retailer. “I’m thinkin’ of buyin’ some myself,” he adds. “These guys in Bali or Vietnam are very good at what they do, and they do it for a bowl of rice.”

He used to make coffee sets, too. One, which he fired in Nelson’s first wood kiln, was sold to a Motueka gift shop. Almost a decade later, Fullmer was amused to find that it was still there, so he bought it back—for a princely $29. In the meantime, he began entering the Fletcher Brownbuilt Pottery Award.

At the inaugural award ceremony in 1977, Aucklander John Anderson collected his $2000 first prize wearing a green sweater with torn-out elbows, patched-up jeans and gumboots.

During the 21 years it was held, the Fletcher became more of a champagne flute affair, establishing itself as one of the three most prestigious pottery competitions in the world, along with Faenza in Italy and Mino in Japan. Fullmer won the Fletcher in 1986, and then again, jointly with Chester Nealie, in 1987. Business has been good ever since.

Yet in the broader picture Fullmer and Robertson are exceptions to the rule. The majority of potters operate in a more marginal zone between a bread-winning occupation and an expensive hobby.

The rate of attrition in recent times has been high. Twenty years ago there were some 500 full-time professional potters in New Zealand, and some 44,000 people professed an active recreational interest in ceramics. Today there are fewer than 100 potters making a full-time living from the clay.

[Chapter break]

Without fire, clay is just civilised mud. It is the partnership with heat that transforms earth into art. As potter Uraeme Storm has put it: “Having offered the fire the best hands and heart can do, you receive back from it, maybe days later, its casual nod of approval, that flash of glory that outdoes even your wildest hopes. Or perhaps a blighting comment on your petty presumptions to immortality. That actual moment of opening the kiln, that’s when you know beyond all doubt that you do not work alone.”

Although today’s electric and gas-heated kilns offer the convenience of controlled heat on demand, there are certain effects that can only be achieved in a wood-fired kiln, and the pinnacle of wood firing is a primitive-looking set-up called anagama.

Anagama firings are rare events requiring truckloads of firewood, round-the-clock attention and a location where fire regulations are not too stringent. Darryl Frost has an anagama kiln on his property at Canvastown, an hour’s drive east of Nelson, but when we pass through we learn that his next firing will be three or four months away. “Come back then,” Mark James, another Canvastown potter, suggests. “It will be an exciting time.”

It is early autumn when I make my way back to Frost’s property to witness the “moment of truth.” James and three other potters are there—wood firings tend to be communal affairs—and we all gravitate towards the kiln, which is still warm to the touch, even though the fire in its belly has been extinguished for almost a week. Anagama, from the Japanese for cave, refers to a single-chamber tunnel kiln shaped like a brick igloo. This one has been built against a clay bank. It slopes upwards from a crawl-in entrance at one end to a tall flue at the other. A vase of wilted flowers decorates the top—”an offering to the gods of fire,” explains Frost.

A corrugated iron lean-to protects the kiln from the elements, and there is a motley collection of chairs and an old bus seat clustered around the kiln entrance. A scatter of empty wine bottles suggests that the firing has been quite a party.

Packing a kiln like this is an art in itself. The idea is to channel the flames around the work in such a way that you can predict which surfaces will be most exposed to the fire. “Though with this sort of firing you can’t guarantee anything,” Frost cheerfully admits. Once all the nooks and crannies are filled, the fireworks begin.

For five days and nights the potters took turns stoking the beast, throwing in pine slats every few minutes until the temperature reached 1300°C. Through small hatches in the sides they threw in totara shavings, cabbage-tree leaves and salt. Salt and wood ash form a glaze, and also act as a flux, binding glaze to pot.

Apparently, things got a little out of hand at the hottest point, and the temperature bolted up by 50°C too much, resulting in a major meltdown in the front of the kiln, that’s when you know beyond all doubt that you do not work alone.”

Although today’s electric and gas-heated kilns offer the convenience of controlled heat on demand, there are certain effects that can only be achieved in a wood-fired kiln, and the pinnacle of wood firing is a primitive-looking set-up called anagama.

Anagama firings are rare events requiring truckloads of firewood, round-the-clock attention and a location where fire regulations are not too stringent. Darryl Frost has an anagama kiln on his property at Canvastown, an hour’s drive east of Nelson, but when we pass through we learn that his next firing will be three or four months away. “Come back then,” Mark James, another Canvastown potter, suggests. “It will be an exciting time.”

It is early autumn when I make my way back to Frost’s property to witness the “moment of truth.” James and three other potters are there—wood firings tend to be communal affairs—and we all gravitate towards the kiln, which is still warm to the touch, even though the fire in its belly has been extinguished for almost a week. Anagama, from the Japanese for cave, refers to a single-chamber tunnel kiln shaped like a brick igloo. This one has been built against a clay bank. It slopes upwards from a crawl-in entrance at one end to a tall flue at the other. A vase of wilted flowers decorates the top—”an offering to the gods of fire,” explains Frost.

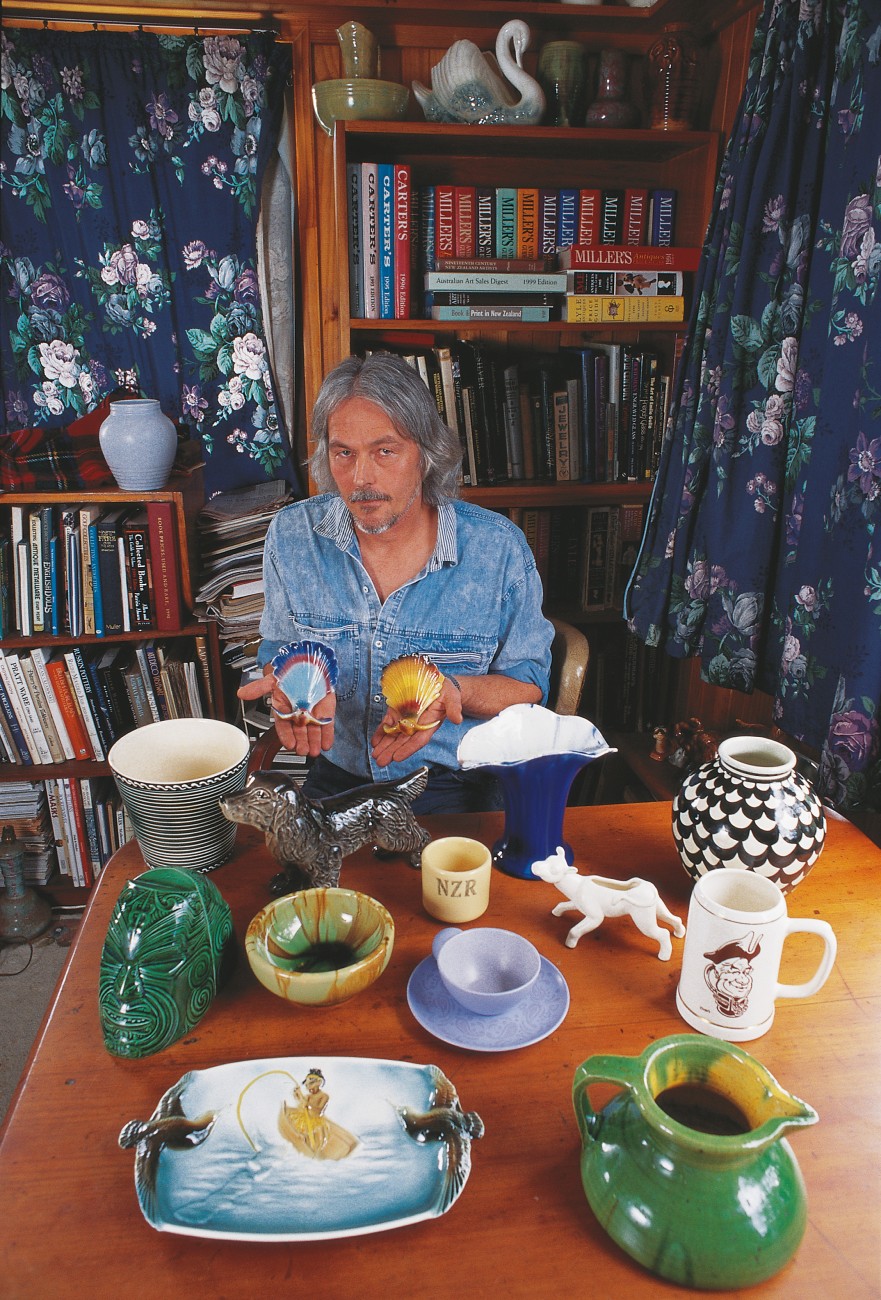

[sidebar-1]

A corrugated iron lean-to protects the kiln from the elements, and there is a motley collection of chairs and an old bus seat clustered around the kiln entrance. A scatter of empty wine bottles suggests that the firing has been quite a party.

Packing a kiln like this is an art in itself. The idea is to channel the flames around the work in such a way that you can predict which surfaces will be most exposed to the fire. “Though with this sort of firing you can’t guarantee anything,” Frost cheerfully admits. Once all the nooks and crannies are filled, the fireworks begin.

For five days and nights the potters took turns stoking the beast, throwing in pine slats every few minutes until the temperature reached 1300°C. Through small hatches in the sides they threw in totara shavings, cabbage-tree leaves and salt. Salt and wood ash form a glaze, and also act as a flux, binding glaze to pot.

Apparently, things got a little out of hand at the hottest point, and the temperature bolted up by 50°C too much, resulting in a major meltdown in the front of the kiln. Peering into the entrance, I can see where some of the shelving has collapsed. Glaze has run like lava and fused many of the pieces to the kiln floor. The whole assemblage looks like an abstract sculpture—original and arty, if only it could be pulled out through the cave’s narrow entrance.

“We are prepared for a 50 per cent loss rate,” says Frost, ruddy-faced and excited, as he digs a screwdriver into the outer clay layer of the kiln, dislodging bricks to open the side door.

He’s not far off the mark. The shard pit will get its fill of rejects today, but the potters are unfazed, focusing on what did work out. They are like kids comparing their Christmas presents. Most of the time, the fire can do no wrong: “Look! It’s all melted! Excellent! And this one didn’t melt! Cool!”

Many pieces have had scallop and cockle shells pressed into the clay, and these have partially melted, leaving their imprint but streaking away at the edges as if they were made of wax.

“It’s always a surprise,” Frost says. “Every firing is a grand experiment.” And a spectacular one. On one occasion an airline pilot spotted flames shooting up from the flue and reported it to the Christchurch control tower, which in turn relayed the warning to the local fire brigade. The duty warden was said to reply: “Oh, don’t worry. It’s only that old pyromaniac Frost.”

If anagama is the potter’s orgy of fire, then raku must be the barbecue version. Whereas anagama takes a week or more, a raku firing is over in about an hour. Both venerate the unpredictability of the flame.

Raku also originates in Japan, where since the 16th century it has been mainly used to produce bowls for the ritual tea ceremony. During the shogun era, a raku bowl was a prestigious gift, and today those that once belonged to the great tea masters can sell for $200,000 apiece. Affluent Japanese families still occasionally organise a raku soirée, hiring an itinerant rakuist with his portable kiln. The guests decorate the prefired bowls and the potter fires them on the spot, ready for the tea to be served.

During raku firing the thickly glazed pots are heated to about 1000°C, when the glaze is melting and the clay glowing red-hot. They are then removed from the kiln with long tongs and welders’ gloves, placed in a drum full of sawdust, leaves or wet newspapers, and covered with a lid.

The lid causes oxygen starvation of the fire, haphazardly altering the colour and texture of the glaze. When exposed to the air again, the surrounding fuel bursts into flame once more, then burns away as the pots cool. The soot and ash are then scrubbed off to reveal surprising colour effects, often reminiscent of an aurora or an oil slick. The work has the porous texture of volcanic rock, and looks aged, as if the pots had just been unearthed in an archaeological dig.

As with anagama, the results are about as foreseeable as a lottery draw, and losses are high. But for rakuists this only adds to the excitement. Every so often the fire produces a masterpiece, and it is from such magic moments that the technique derives its name, one translation of which is “happiness through chance.”

Whether they practise raku or not, most potters would say that the creative epiphanies they experience in the course of their work are the reason they endure economic hardships or fickle public tastes. They will tell you that pottery is more than a business, more than craft or art. It is a philosophy, perhaps even a spiritual quest.

[Chapter break]

Such a credo is held by the man who was the first craft potter in Nelson: Czech immigrant Mirek Smigek. In 1952, after a stint at a Canberra brickworks and two years with Crown Lynn Potteries in Auckland, he moved to Nelson to manage the Nelson Brick and Tile Company. There was good, cheap clay in the hills, he discovered, and the attraction of the potter’s wheel became so strong that he left the world of industrial ceramics to set up his first studio behind Tahuna Primary School. Children would climb over the fence at lunchtime to watch him work, mesmerised by the miracle of pots blossoming beneath his fingers. When, after 17 years, Smgek moved to the North Island, there were over 20 established potters in the “land between the rivers,” many of them trained by him.

From his house at Waikanae Beach, Smigek can draw inspiration from panoramic views to Kapiti Island in the west, the Kaikouras to the south and the Tongariro volcanoes to the north. The rims of his vases echo the skyline ridges of the Tararuas, their fluting mimics creeks running down the mountains, their decorations the patterns of leaves and estuaries.

The 73-year-old still teaches, willingly and tirelessly, and on the day of my visit his pupil was 12-year-old Daniel Fraser.

Together they prepared clay for the wheel, cutting it with a wire and kneading it to remove even the smallest of air bubbles, which could, during firing, cause the pot to explode inside the kiln and shower other pieces with shards that embed themselves in the glaze, marring the surface irreparably.

The boy was restless to produce. A bowl. A cup. Something. Anything.“Slow down! Be patient,” Smisek said. “The important thing is to feel the clay. Never rush it.”

When the clay was finally ready they moved to the wheel—a metal turntable powered by an electric motor. Smfgek plopped a ball of clay on the turntable and footed the motor into life.

“It is critical that you centre the clay before throwing,” he continued. “If you don’t, the pot will spin like a punctured tyre. Its walls will be uneven, it will be out of shape and off-centre, it may even collapse before you finish. Now watch!”

He held the clay firmly until, under his hands and the power of the revolving base, it took the shape of a perfect cone. Then his thumbs found their way inside the clay, and suddenly the bud-shaped cone opened like a flower in a time-lapse movie. It was a moment that never failed to amaze the Tahuna kids, Smfgek told me.

Soon enough it was Daniel’s turn. Pupil and master shaped the first bowl together, then a second, then a third, and each time Smfgek helped less and less. Then he quietly withdrew to another wheel, and left the boy to his own devices.

“You’ll throw away many pots before you throw a good one,” he cautioned. “Practice is everything. Think of a musician playing scales and arpeggios. The freedom of expression can only come from skills, and these come through repetition.”

Many a student has balked at the prospect of such seemingly endless practice. One of this country’s founding potters, Thomas Lovatt, used to employ school pupils at his Wellington factory during the 1930s. They generally found the work repetitive, hard and menial—hardly the opportunity for creative expression they were looking for. One who persevered—Allen Collins—would later recall his unforgettable first day at the pottery, when Lovatt sat him at the wheel and told him to keep throwing until he had made a saleable item—a task that took him three months. Eventually Collins could produce as many as 350 pieces a day.

Smigek worked as we talked. He threw one large plate and decorated another. “Clay requires attention at precise moments,” he smiled. “You must forgive me.”

He told me how the Second World War had coincided with his formative years; how in 1943, when he was 18, he escaped from Nazi Germany to neutral Switzerland, crossing the confusing frontier near Schaffhausen, only to make a navigational mistake and walk straight back into the machine guns of German border guards.

The next two years were a nightmare of Gestapo interrogations and 13 prisons and labour camps. “In those camps, and in the other atrocities of war, I saw and experienced the lowest and the most destructive side of human nature,” he said. “Ever since, I’ve been trying to find a counterpoise and a remedy, and I’ve found art and creativity—and pottery in particular—to be my most potent antidote.”

His favourite tool of expression is a foot-powered kick wheel, built 50 years ago from parts salvaged at the old Nelson brickworks. It is quiet and smooth and affords perfect control, Sinigek explained. To me, it spun with the purposefulness and meditative calm of a Tibetan prayer mill.

There came a cry for help from Daniel’s wheel: he was experiencing a major puncture at high velocity. The clay was wobbling heavily off-centre, oozing deformities through his fingers. It was hard to imagine that it could ever again become that perfect cone which is the beginning of a shapely pot.

But then it happened. Smgek put his hands on top of Daniel’s—old knobbly hands cupping young, impatient fingers, re-centring the clay, guiding, supporting, imparting skill. He spoke again of the need for gentleness and patience, of not rushing the clay, and you could see that the words were no mere art prattle, but a knowledge that comes from focused hours and disciplined years spent in pursuit of a passion.

Watching him work, listening to him teach, you couldn’t help but feel that for this old man clay—and life—no longer had secrets, only mystery.

[Chapter break]

From Waikanae I continued north, visiting studios and galleries as they appeared, buying a piece here and there, and making a list—a long list—of objects I craved but couldn’t afford. In the back of my station wagon I viewed with satisfaction the modest collection of clay postcards from my improvised pottery trail—each wrapped in folds of bubble foil, each a souvenir from a memorable encounter. There was a Steve Fullmer wine chiller—coolly understated and practical—and a Joanne Wilson coffee set that mimicked the skin of a rainbow trout just before it spawns. There was a salt-glazed teapot, a raku vase, a sushi platter and some tongue-in-cheek gifts for friends at connubial crossroads. These were the work of Nelson’s Anna Barnett, who keeps alive the Sumerian tradition of writing tablets, though her epigrams fret on decidedly Y2 K themes. “Be nice to your kids—” ran one, “remember, they will choose your rest home.”

There were cereal bowls, a lidded tureen, a voluptuous salad bowl, even some terracotta trays for my cactuses. But only now did I realise that I had not found any porcelain in my travels.

Porcelain, from the Italian word for cowrie shell, which it matches in delicacy and unblemished whiteness, was first brought to the attention of the European aristocracy by Marco Polo. It was resonant when struck and translucent when held to light. It came from the Orient, and it exuded imperial nobility. Like gold, it was rare and expensive, and thus commanded prestige for its owner. And like gold, it defied attempts to solve the mystery of its making.

It was not until the early 1700s that a Saxon alchemist, Johann Boner, and a physicist, Ehrenfried von Tschirnhaus, cracked the porcelain code and became known as the first of the arcanists, the keepers of the secret. What they discovered was that porcelain requires three ingredients: a feldspathic rock known as petuntse, white kaolin clay and silica sand, which together form the body. When fired at 1300-1450°C, the petuntse vitrifies, fusing all the ingredients to give an ivory-like finish.

Towards the end of the 18th century, European potters actually managed to improve on the original Chinese formula. Josiah Spode the Second experimented by adding bone ash to the true porcelain mixture. The result was bone china, and it was much less prone to chipping than the Chinese ware. It was that kind of porcelain that Utz so hopelessly fell in love with.

I had not seen any porcelain in my travels (though I would later visit a porcelain clay pit in Northland), but perhaps New Zealand was not a porcelain kind of country. Avalanche-prone mountains, the harsh glare of the sun, rivers wild in flood—these elements do not inspire rococo chinoiserie. You could bring it here, but, like a fragile exotic plant, it would struggle to put out roots. This land was too fresh and too raw, free-spirited in its forms like lava that had not yet settled, porous and absorbent like Taupo pumice.

The world’s whitest and most expensive clay is found in Northland. New Zealand China Clays exports this high-quality raw material from its works at Matauri Bay, north of Kerikeri, around the globe. As well as being an ingredient in the finest porcelain and bone china, including Limoges, Lladro and Noritake, Matauri Bay clay is also sought after in the technical ceramics sector, where it is used in such products as molecular sieves and catalytic converters.

When European settlers arrived in this corner of the Pacific, they wanted to leave much of their burdensome traditions behind, to free themselves from the rigid moulds of their old societies, to start anew. Their place-naming reflected this desire: New Britain, New Ireland, New South Wales, New Holland, New Caledonia, New Zealand. Everything was to be new. So why not new pottery?

“Those early settlers had to make everything themselves, including pottery,” says West Coast ceramic artist John Crawford. “They were isolated from the rest of the world, from outside influences, and so what they created was spontaneous and informal, a reflection of their needs.”

Earth-coloured brownware and marble-ware dominated that era, and although some contemporary potters refer to it now as the Dark Age, Crawford insists that it’s the closest we’ve ever got to a pure New Zealand style in ceramics.

We must look inside ourselves and not mimic others, he says, and to this end he’s been rediscovering an isolationist lifestyle for himself, having moved—after many years in Nelson—to the tiny settlement of Ngakawau, north of Westport. His atelier, which he shares with his potter wife Anne, is just across the road from the roaring sea and a beach heaped up with foam and drift‑wood. When the mist rolls in to engulf everything, or when the rains come and stay for days, it’s as soul-searching an environment as you could wish for, with no distractions or outside influences to pollute the artistic process. The sort of space you can still find in New Zealand, Crawford says, space that offers a baptism of fire for your creative self.

In the North Island, the place people migrated to in the 1970s to find their creative self was Coromandel. Like Nelson, this bushclad, sea-washed peninsula was the potter’s promised land. I heard many recollections of how, cresting the last hill before reaching Coromandel township, you’d see black smoke rising in plump columns from dozens of kilns.

In those days, properties were cheap, clay and timber plentiful, and council building codes relaxed. The market for pots was good, too.

Then came the change—the second act in the boom and bust saga. Changing tastes. Cheap imports. Most of the Coromandel potters from the ’70s have left. In one craft shop I visited on the peninsula, the owner admitted that there was not a single hand-thrown piece among her offerings. A lot of Balinese cotton though; that’s the new line of business.

One potter who didn’t leave, and who casts a long shadow in this part of the world, is Barry Brickell, the pioneer of Coromandel pottery. Today he is as famous for his bush railway as he is for his ceramic work. He laid the rails himself to give access to seams of clay in the hills of his property, but the miniature locomotive that carries tourists around the area is now a bigger drawcard than the pottery that is still being made by Brickell and his protégés in a rustic clutter of huts and kilns set in the native bush.

One of Brickell’s undoubted contributions to craft pottery in New Zealand is the work environment he has created. He offers studio space, clay and fire, and so far over 120 potters have stayed and worked for a time at Driving Creek.

His current potter in residence is Erik Omundsen, a 25-year-old native of Montana. He showed me his latest work: a curvaceous bottle so large he had to build it inside the kiln. After firing, it will shrink enough to be pulled out through the entrance. But his next sculpture, built with only fingers and no tools, will be even larger, he said, requiring approximately two tonnes of clay. It will be so large that he will have to construct a kiln around it.

Yes, but will it sell?

Omundsen may not have to worry about such questions, but throughout my impromptu tour of the country’s clay-workers I met many who admitted that the bottom line was cramping the bohemian lifestyle they had known in the past.

Some, through exhibition success, have secured a measure of financial security. John Crawford’s insular soul-searching has certainly paid off. He has had three solo exhibitions in Germany, and is now in the fortunate position of being able to sell whatever he makes.

Others have diversified, finding commercial ventures to finance their art. One man with several pots in the kiln is Brightwater’s Royce McGlashen. Trading under the name Mac’s Mud, he supplies 300 tonnes of clay a year to potters around the country. At the same time, he operates a tidy boutique studio that is small enough to produce any number of speciality lines, yet large enough to attract business from bulk users such as the hotel trade.

McGlashen also finds time to pursue his own career as an artist, in recognition of which he was invited to join the International Academy of Ceramics, the only potter in the country to have that honour.

In this crafty blend of business and art, 50-year-old McGlashen, backed by his wife Trudi, has managed to reconcile the pressures that cause mental schism in many a creative soul: how to be true to your art and still keep the wolf from the door.

His recipe for success? No secret, really, McGlashen says. Get up early, work hard. “I come from a poor family,” he tells me. “We never had much material wealth, so, perhaps in compensation for that, I’ve always aspired to succeed. My mother, a painter, told me: ‘Royce, you’ll never make it as an academic, but you’re good with your hands. Use them.’ And she told me something else: ‘If you do something, do it well, with all your heart and mind, and no half measures.’ I’ve always tried to follow that advice.”

[Chapter break]

Amongst Mcglashen’s artistic accolades is a merit award in the 1987 Fletcher Challenge Ceramics Award, for a porcelain teapot. Recently, however, the Fletcher has become a sore point with New Zealand ceramists. In 1998, the Norwegian potter Torbjorn Kvasbo was invited to judge the competition. He came, he looked . . . and he shook his head. Of the 791 entries—most of them from New Zealand—he said, “I really liked 20. Another 50 I could live with, and I was forced to include a further group that I didn’t really care for in the 94 works for exhibition.” Eight New Zealand entries made the final cut; not one won an award.

In his comments, the judge hinted at a lack of artistry in the New Zealand entries—an assessment which did little to endear him to local potters. “Ceramics has to be both mental and physical work,” he said. “There is not enough mental work in a lot of New Zealand pottery.”

Kvasbo contrasted the way studio pottery is pursued here and in Scandinavia. In his country, he said, most potters would spend a minimum of five years training at university, and that would entitle them to belong to a trade union. “It is impossible to work there if you are self-trained and do not belong to the union.”

But that’s not the only contrast between Kvasbo’s part of the world and ours. More people go to art exhibitions than to sports events in Norway, and the arts are more important to the country’s economy than forestry, farming and fishing combined. Kvasbo himself gets a government scholarship equivalent to $2500 per month until he is 67 for creative exploration in pottery—and he is by no means the only recipient of long-term government support.

Might the do-it-yourself Kiwi attitude be dissipating artistic focus?

Royce McGlashen doesn’t think so: “It is one of this country’s greatest assets that we are not bound by centuries of tradition—tradition which offers security and stability, but which also imposes artistic tunnel vision and an obligation to conform. We have the freedom to look at all the influences, adopt what we like and discard the rest.

“With that comes a responsibility to be totally open to ideas, to question everything, to allow our styles to continually evolve and renew themselves,” he continues. “Our ceramic landscape is limitless, and we’re only too pleased to wander around exploring it.”

My own wanderings in this landscape had come to a temporary end, and I drove home, contemplating its changing vistas, paying silent homage to my many guides.

The summer was nearly over. Jacou Vettard was back in her studio, wrestling with clay and a torrent of new ideas, and I returned to a desk piled with books and letters.

But from behind the computer screen I now look along the window sill to where, from a new terracotta tray, my cactuses are craning their happy limbs towards sunshine. In an oblique kind of way, the country’s potters remind me of cactuses. They are prickly with artistic pride. They eke a living out of baked earth, and their work blossoms unpredictably, though often with astonishing beauty. They have stood their ground stoically, weathering the arid economic climate and, moreover, our taste for pottery, which has gone a little dry. But resilient as they may be, they still need the occasional limelight of our attention; they still need watering, however infrequently.

For myself, I now habitually turn down those gravel roads signposted “Pottery,” and have learned to look at everyday tableware with new eyes, and a certain degree of wonder. I also asked Jacou to make me a new dinner set and to decorate it with the colours of our home town: the deep yellows of autumn poplars and rose hues of the mountain snow catching the first of the morning sun.

The other day she brought them round. Just out of the kiln, they were still hot, like freshly baked bread.