100 metre man

William Trubridge’s quest to dive a hundred metres on a single breath.

Holding your breath. It’s as simple as that, and as hard. Try it now as you read. Take a quick deep breath… hold… and read on.

Right now you are trying to assess how much air you’ve managed to cram into your lungs. You’re facing the sure knowledge that very shortly, probably inside a minute, you will experience an overwhelming urge to breathe, to open your gullet and and suck in great life-sustaining draughts of fresh air. How will you cope with that moment when it arrives?

Now imagine that at this point of panic, you are 30 m into a dive, a dead weight in the water, and freefalling into an abyss to retrieve a Velcro tag that is still a further 70 m below. From there, the safety of the surface is 100 m back the way you came. But at this depth you have negative buoyancy, and so for the return, you must kick and stroke your way up the height of a 30-storey building. You have no fins, just your bare hands and feet.

In all, you will be swimming 200 m on that one breath. Soon enough, as you read, you will begin to feel the onset of that uncontrollable need to breathe, where your resolve breaks up into paroxysms of panic. Panic, gasp for air, and you will sink like a stone, lost to the deep.

Be calm, Understand that your body has oxygen for many more minutes and that you must work through this desperate desire to gasp for air. Your bodily tissues and blood are charged with oxygen. Be calm, reach the other side.

[Chapter Break]

Holding your breath. We’ve all done it as children in the bath or at the beach. This story is about how world champion Kiwi freediver William Trubridge turned that one breath into a diving ability that can rival some aquatic mammals—a story of endurance, obsession and science. A spiritual journey even. How does he do it?

And yes, if you’ve lasted this long–take a breath. Reading this far should have taken about a minute. Trubridge can hold his breath about eight times longer.

I ask him if he realises there’s something monumentally absurd about diving 100 m on one breath. “Sometimes I get a flash of how different it is, sure. Most of our lives, we live in the air element so that’s the norm. We are not always aware that we have the capacity, and always have had, as other animals do, to suspend breathing for quite long periods of time.

“Aquatic mammals have spent millions of years evolving for the dive and the beautiful thing is that somehow I have rediscovered my own evolutionary roots.”

All mammals have a hard-wired physiological response that aids survival and reduces oxygen demand. It’s triggered by water on the face—it has to be cold water (less than 21ºC) and no other body part will suffice. It’s as if your whole face is a button, and here’s what this button does.

When submerged, receptors in the face send a signal to the autonomic nervous system, slowing the heart rate 10–25 per cent, reducing the consumption of oxygen. The capillaries at the extremity of the body also start closing off—fingers and toes close off first, then limbs and some organs, creating a heart brain circuit. Finally, at crushing depths, blood plasma is able to move freely around the thorax, permeating organs which would otherwise rupture.

Humans elicit this response when we splash our face with water when upset, to reduce our heart-rate, or when we decide to hold our breath and plunge to the seafloor.

I picture a school textbook graphic showing the relative performance of aquatic mammals, with Trubridge down there mixing it with whales and dolphins.

“I can definitely out-dive a polar bear,” he says. “There are very few aquatic mammals of similar size that don’t have greater capabilities, but the thing is that I am comfortable down there, at one with their world.”

It’s certainly true that freedivers have vastly extended their underwater endurance. When Trubridge was born in 1980, the world record in “No Limits” freediving—rocketing down with a weighted sled and riding back up with an ascent balloon—was 100 m, held by Jacques Mayol, the subject of Luc Besson’s epic 1988 film The Big Blue. Now 30 years old, Trubridge is reaching the same depth in the purest form of the sport, without the use of any propulsive aids, not even fins.

“When I first got into freediving, under the guidance of my mentor Umberto Pelizzari, the world record without fins was 60 m. It seemed like a freakish, unrepeatable performance. As I started to discover the sport, I realised that the boundaries might be a lot deeper. I realised if you can dive to 50 m, you can dive to 51!”

At one point in training Trubridge reached 88.5 m.

“I realised that depth was one per cent of the height of Everest. I thought, ‘That is cool. I have dived one per cent of his [Sir Edmund Hillary’s] achievement. Now we Kiwis have both ends covered!’”

When Trubridge was an infant, his parents sold their house in England to buy a boat, which they sailed from Spain across the Atlantic, Caribbean and Pacific to New Zealand. Like Hawaiian children, he learned to swim and walk at the same time, and by the age of eight was competing with his older brother, Sam, to see who could bring back a stone from the deepest depth.

Trubridge didn’t realise that freediving was a sport until 2003, when he travelled back to the Caribbean and became hooked, spending hours underwater every day descending huge coral walls or lying in sand gardens watching tropical fish.

“There is nothing more exhilarating than gliding effortlessly through coral ravines, or swooping down a rocky drop-off into the abyss,” he says. “You’re a mere human, flying free. On one breath.”

But the sport of freediving, like most sports, isn’t about such lyric foolishness. It’s divided broadly into two basic kinds. First, there is diving without assistance, where not even fins are allowed. And then there is diving with assistance that can range from riding a sled to depth and then inflating an ascent balloon, to merely the use of fins.

In both types, a white plate is attached at the goal depth on a descent line. The diver, who must recover a Velcro tag from the plate, is in turn attached to the line by a lanyard and carabiner, which slides down the line. In the event of a mishap, safety divers stationed along the line can provide an ascent bag or signal colleagues at the surface to haul the diver to safety.

Oddly, it’s these scuba divers who are most often at risk. That’s because breathing compressed air at depth courts an attack of the bends. Freedivers face no such threat—they are holding the same breath of air they inhaled at the surface.

“Jacques Cousteau wrote that man carries the weight of gravity on his shoulders and has only to sink beneath the surface and he is free,” says Trubridge. “But scuba divers can’t dive as deep on air as freedivers can on a single breath. And with the mask, the tanks, the gear, it’s a different experience. Umberto Pelizzari describes it very succinctly: ‘The scuba diver dives to look around, the freediver dives to look inside.’”

The freediver’s skill is understanding how to survive on just one breath, to get past that instinctual compulsion to breathe. Or more specifically, to exhale. It’s triggered not by the dearth of oxygen, but by the build-up of carbon dioxide. (Hyperventilating, rapidly breathing in and out, is avoided by seasoned freedivers as it cannot increase the oxygen saturation, but rather artificially reduces carbon dioxide and increases blood pH, putting divers at risk of hypoxia.)

Training is about developing flexibility, both in the muscles and in the lungs. Most days Trubridge swims kilometres underwater. But it is yoga—with its pranayama breath-control exercises, the use of bhanda tongue locks and empty-lung breath holds that provides the most critical tools.

“If you can push past that first panic, it’s then all about your physiological ability to survive,” Trubridge says. “It takes a lot of training. If you can relax despite the contractions, you can remain calm and focused.”

A freediver must be aware not only of the hostile environment he is entering, but also of what air is doing within his body. Recently Trubridge was forced to abort a dive when the action of rolling over to commence his descent compressed the air in his chest, pressed it past his glottal stop and caused it to enter his stomach. The problem then was two-fold. He had suffered a critical loss of air volume available for respiration, and he would have to face the difficulty of managing air in the stomach. To understand that, think back to the childhood trick of producing belches by pushing air into your stomach. It’s not something you want to deal with at 100 m.

During a dive, the yogic technique of pushing against the roof of his mouth with his tongue helps Trubridge to quell the contractions of his diaphragm. But at depth, he faces another foe. That simple lungful of air he inhaled at the surface will turn against him, it will addle his mind, it will poison his body.

At 30 m, nitrogen begins to exert a powerful narcotic effect. At first, Trubridge will experience a feeling of tranquillity, but as he descends further, it is manifest in overconfidence, delayed responses, dizziness, poor concentration, hallucinations, a flawed sense of time and effects on psychomotor functions. If this list seems familiar, it’s because it is very similar to alcohol intoxication. And the deeper the dive, the more dramatic the effects—at an extreme the diver can become so befuddled they simply pass out.

So let’s make this quite plain. Trubridge, like all humans, is a creature optimised for the world of air and light. Despite his expertise, despite the benefit of the mammalian diving reflex, this is an audacious trespass into a world he has no place to be. He will swim into oblivion for two minutes on a single breath. At 100 m below the surface he will be subject to 11 atmospheres of pressure, his lungs will be the size of grapefruit, and, in this most uncompromising position, he will be effectively drunk.

[chapter-break]

It isn’t necessary to dive 100m to experience at least some of the physiological challenges of the sport. Static apnoea—holding your breath without movement, either in water or on land—gives a strong sense of the sheer willpower required to transcend that most basic human instinct of breathing and to enter a world quite beyond the frontiers of our everyday existence. Trubridge can hold his breath with static apnoea for eight minutes, a feat achieved not so much by physical condition but by mind over matter.

It’s a technique that can be taught. Trubridge runs a freediving school with his wife, Brittany, on Long Island in the Bahamas. It is also the site of the world’s deepest marine blue hole—a massive sinkhole surrounded by a fine white beach and shaped like an hourglass, the narrow waist at 30 m and the bottom lost in darkness at 202 m.

Join Trubridge’s school while you’re reading this feature. You might just catch a glimpse of his world, down deep in the big blue. The combination of tongue locked against the roof of the mouth and the knowledge there is calm on the other side of the contraction can transcend the panic. Follow Trubridge’s preparation now, and in a moment take the plunge with him into Dean’s Blue Hole.

“By visualising the dive, I install it deeper in my subconscious. In the morning, I will often do that again. I visualise each stage: approaching the dive site, the time in the water, the breathing. What ups the ante is not so much the dive but what’s at stake. Am I trying for a personal best, or a world record? Who’s going to be there? At any time during this visualisation, if I encounter a problem I know that’s something I need to work on and resolve. When it comes to the dive, it reinforces the sensation that I have done it before.”

Lying flat on his back floating at the surface before the dive, his feet supported on a rubber ring, Trubridge goes through a sequence of lung-stretching exercises. He has to ensure his whole thorax is pliable so that it can slowly crumple under the pressure of 11 atmospheres as he descends.

He relaxes his mind as well. “I try to eliminate thoughts, or at least to extend the gap between them. You can’t actively resist thoughts. But if you just wait, the empty space between thoughts will grow. If you consciously start thinking, ‘I am going to dive’, then that adds to stress. And that uses oxygen.”

He waits on the surface until his venous oxygen saturation is as high as possible.

“You must know how you are breathing—make sure it’s shallow and neutral. If you start to get tingling in your fingers, that’s a sign you have over-breathed. You have to get it right at this point, because it’s too late once you are down there.”

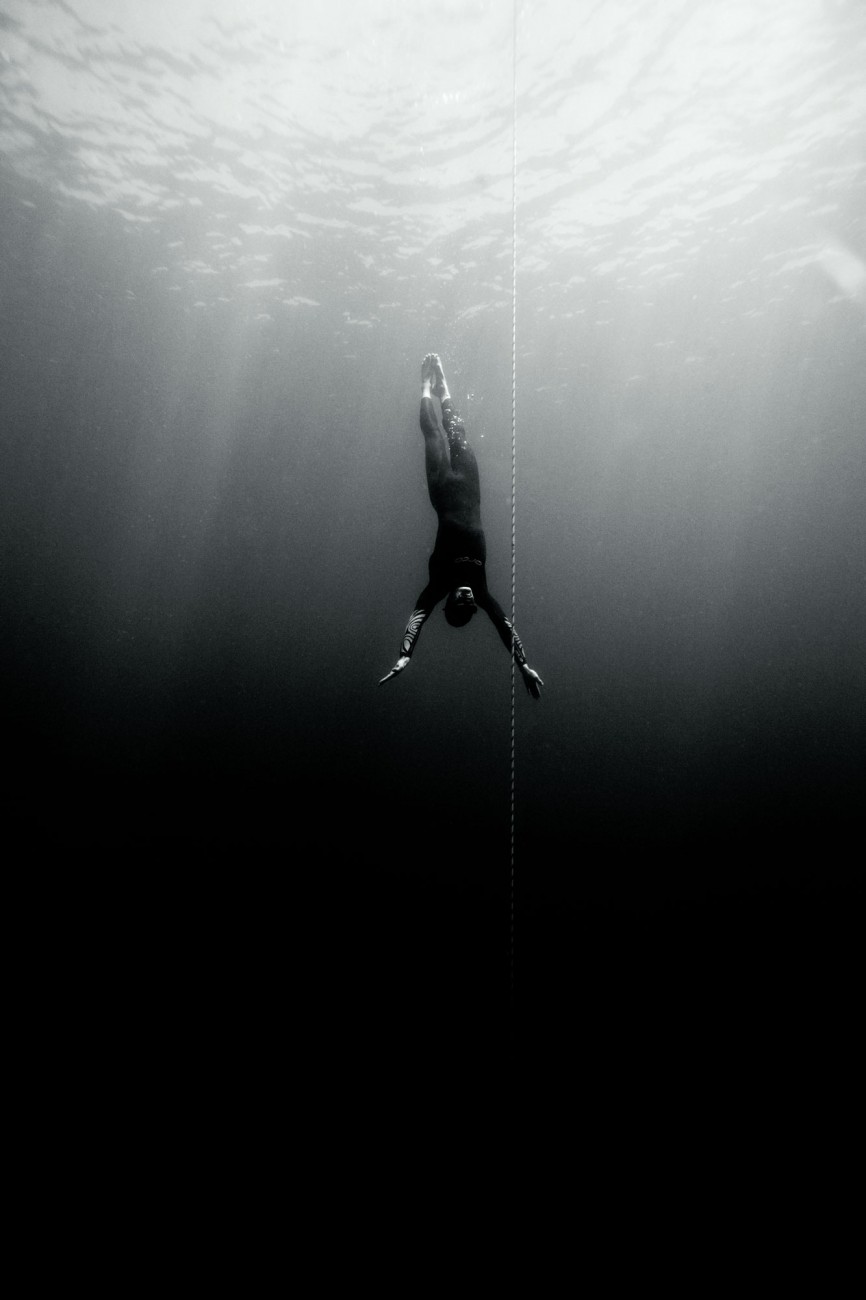

The descent line, leading the way into the steely depths, is cupped in his armpit. Trubridge’s chest is swollen like a barrel, his goggles are on, his face is locked heavenward, lips pursed. It’s as though he has already departed the world that most of us know. Around him a swarm of snorkelers orbit in support. Judges, timekeepers and medical staff watch on in silence.

He draws his last full breath, stirs from his trance, and bites at the air like a dog chasing the wind, using his mouth and tongue like a pump to pack an extra couple of litres of air down his trachea into the lungs. This increases the pressure in his lungs to slightly more than one atmosphere.

Trubridge rolls onto his side and heaves his frame beneath the surface. From the world he was designed for to a hostile world without compromise. From a world with air to a liquid realm without.

0m //00:00

The clock starts when I roll over and begin the descent. I try to keep my eyes half-closed, to reduce stimuli and distractions, but open enough to make sure I am following the line. I monitor my own internal state, working with my mind and body to relax, to work through any contractions. I keep telling myself mantras to shut down all thought processes, so I don’t anticipate or mark off how deep I am, or how long I have to go.

“I have to commit to the idea of letting myself go, with no perceived end or boundaries to that. I find a deeper state of abandon and relaxation, with no thoughts of where I am.”

30m//00:30

The mammalian dive reflex kicks in. I want the dive reflex to be quite sudden, the more magnified and sudden the greater the beneficial response.

“My heart rate is slowing down. The lungs are contracting. As the lungs collapse, the blood swells the vessels and the lungs fill up with blood like a sponge. The extremities are pushing the blood into the core of the body, to feed the heart and brain. All that physiological adaptation contributes to tension, so my blood pressure goes up, and to counter those effects the heart rate drops right down.”

If you have chosen to take a last breath with Trubridge and join his dive, you won’t be aided by this dive reflex, but neither will you have the stresses of the dive, or the sensation of passing through a portal into darkness as your body becomes negatively buoyant and you freefall past the lip of the blue hole at 30 m.

50m//1:00

Like a skydiver, Trubridge is falling through fluttering gently in the turbulence.

“Freefall is the most enjoyable part of the dive, when my body’s buoyancy becomes less than the specific gravity of water and I start to sink. I reach a terminal velocity of one metre per second and I can feel that as a gradual increase in pressure on my head.

“Slow adaptation is the key, and, remarkably, the body is more than capable of acclimatising to all these factors.”

75m//1:30

“My lungs have already halved in size at 10m, and with every additional 10 m an extra atmosphere of pressure is added. At 90 m my lungs will be one tenth of their original size. Given that even with a maximal exhale we reduce our lung volume to at the very least a quarter, this means that a deep dive is like exhaling every last drop of air that you can, then using a pump to suck out half of what’s left in your lungs. We have to do a lot of stretching exercises in order to accommodate this level of collapse in the lungs. And once you reach that, your body has to come up with other ways to access oxygen.”

At 90 m, alarms on Trubridge’s depth gauge snap him out of freefall. His arm extends gradually, running down the descent line to touch the plate.

100m //2:00

At the maximum depth he set before the dive, Trubridge is allowed to touch the rope once, remove the Velcro tag with his free hand and attach it to his dive suit, and turn around. His mind fogged by narcosis, this simple movement can be bewilderingly difficult at depth. Ahead of him is the hardest and most active part of the dive. He must prevail over his negative buoyancy, which has been accruing since 30 m, and claw his way back to the surface. It’s like climbing up the rungs of a liquid ladder towards the light. There is no haste; instead, methodical meditational efficiency.

“I never look up because that would stretch out my windpipe. Like a vacuum hose, if you stretch it out it’s more likely to collapse. Down there you can’t see the surface, and thinking about it would spook you out and contribute to negativity. You can’t afford to think of that weight of water above you.

“Instead, I anticipate the ascent, I tell myself that I am looking forward to swimming as an expression of the will to live, the will to survive. I start a kind of fluid rhythmic stroke very much like yoga. It feels like you are collaborating with the water. It’s not like with flippers—you can actually feel the water in your hands and your feet and you can feel it and fold it and move it and push it and you feel in very intimate contact with the water.”

75m//2:30

Trubridge’s kicks and strokes have a metronomic slow-motion regularity, but that belies the hidden danger that stalks every dive—excessive narcosis, where bloodstream gases, under pressure, can cause blackout.

“Narcosis starts to come on towards the end of the descent and it builds during the ascent. You get tunnel vision and a strange rushing noise in your ears. It relaxes you, helps you through the contractions, but when it comes on strong, you worry that you can lose control.”

50m//3:00

Trubridge’s arms and legs have been working anaerobically for some time and are badly fatigued, awash in lactic acid and carbon dioxide. As he approaches shallower water, the threat of nitrogen narcosis wanes, but cerebral hypoxia looms. His oxygen saturation is perilously low, and while ascending, the partial pressure of oxygen in his brain is dropping constantly.

“Once I blacked out at 12 m. I felt the dive was going pear-shaped about 10 m before that, when my thoughts started to get clouded. I waved my head at the safety divers to let them know it wasn’t working out. At that point I blacked out and they brought me back to the surface.”

30m//3:30

At 30 m, Trubridge passes through the neck of the Dean’s Hole bottle and the shimmering Caribbean light returns. “The ascent is the most critical time. I am telling myself to relax, not to speed up. It is important that I stop swimming when buoyancy returns. I have to be calm and ready for the protocol on the surface.”

0m//4:00

Trubridge breaches the surface like a submarine through pack ice, from liquid into gas, from death into life. Clinging to the rope, he heaves in fresh air. But his job is not over.

“With that first breath of air I am concentrating very carefully. You can still black out on the surface. I am pushing hard, bearing down with every breath to get air back into my lungs, oxygen back into the blood. It’s a technique that fighter pilots use to avoid blacking out and deal with gravitational forces.”

Protocol for freediving records dictates that the diver must demonstrate mental competence and fitness. He must remove his goggles and nose clip, and display the tag from the Velcro patch on his swimming gear to the judges. During this time he cannot lower his mouth underwater. It might seem simple, but with the disorienting effects of narcosis, the sequence can be impossibly complicated.

After completing this gruelling sequence, Trubridge cracks a huge grin and punches the air with his fist. As oxygen flushes through his body, so does emotion return to his features. He closes his eyes and hangs on the rope for a moment, his face a picture of relief.

His quest was to push the boundaries of human capability in the purest form—challenging the primal requirement to breathe.

“You can get this thought that this will be the last breath you are going to take, that you are going to die on this dive,” he says. “You can have that at your shoulder.

“But in some way that’s why you do it. It’s about refreshing the will to live. It’s about tasting your own existence by going into that zone where you are toying with death, stepping over that line into a world that doesn’t support life. You are stretching the umbilical cord that connects you to life, but if you go too far that cord could be broken and you can’t get back. You take as big a step as you dare. But your will to live has to match and exceed the size of the step you are willing to take.”

If you can do that, says Trubridge, then surfacing from a dive is like coming back into the world again.