Citizens of the sea

New Zealand is the Penguin Capital of the World, with more than half of all species breeding in our territory. What can they tell us about our seas?

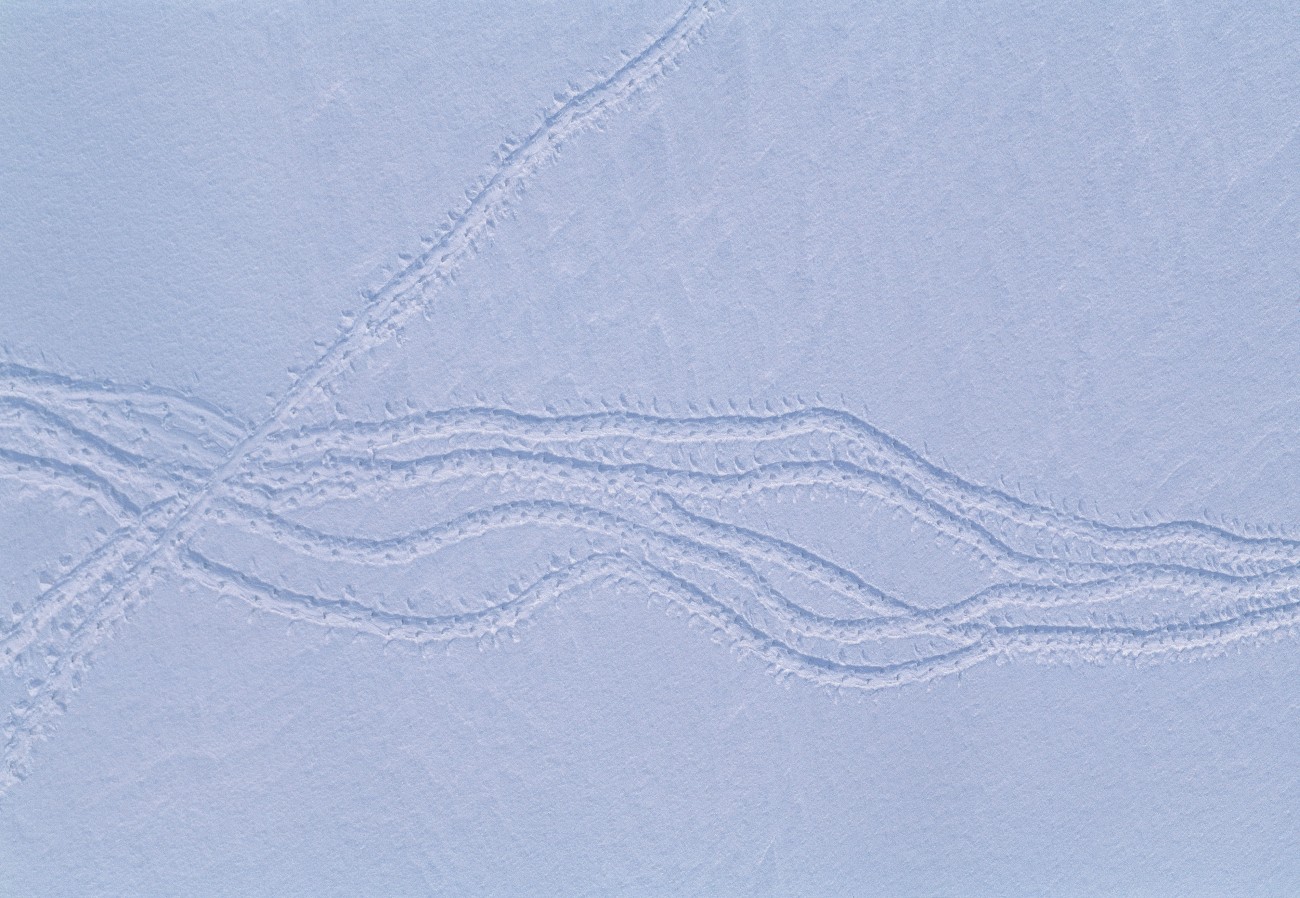

What are little blue penguins trying to tell us?

This spring, penguins in the Hauraki Gulf abandoned their eggs and chicks en masse. What happened?

The future of the world is written in penguin blood

Erect-crested penguins are one of the most mysterious birds on the planet. We have little idea how many there are, what they eat, where they forage, or how their environment may be changing as the Southern Ocean warms. No one has even visited the Bounty Islands where they breed in three years. Scientist Thomas Mattern chartered a yacht and mounted a mission to answer some of these urgent questions before it’s too late.

The wreck of the penguins

Why did hundreds of dead kororā—little blue penguins—wash up on beaches around the country two summers ago? Has their fate got anything to do with the weather? Or has it got something to do with us?

Life on the edge: What penguins can tell us about our seas

Penguins occupy the margin of land and sea, being dependent on both habitats, and vulnerable to changes in either as well. What can penguins tell us about our seas and shores?

Virtual Field Trip: Penguins at the Snares

Explore a Snares-crested penguin colony with 360 video.

Yellow-eyed penguins

The fury of southern South Island seas is a daily hazard for the hoiho, or yellow-eyed penguin—a plucky bird which has become a New Zealand conservation icon.

Opinion: Penguins in the media

Penguins often become flag-bearers for conservation. But does the attention ever make a difference for the birds?

Documentary: Penguins

Penguins are found as far north as the Galapagos Islands and as far south as the frozen heart of Antarctica. Discover how this unusual bird adapts and copes with predators and the incursions of humans.

History: Turning penguins into oil

Joseph Hatch was one of New Zealand’s most tenacious entrepreneurs. He set up the southern-most steaming works in the world and the oil it produced brought significant wealth, first to Invercargill, then to Hobart. It was just a pity that Hatch, who listed his occupation as “oil factor”, meaning oil agent, chose to extract that oil from penguins.

Rockhopper penguins

Leaping ashore through pounding surf, these plucky little penguins congregate each year on remote Campbell Island. But their numbers have declined drastically.

Emperor penguins

Many birds migrate to escape the rigours of winter. Not so emperor penguins, which raise their young in the freezing darkness of the harshest winter on Earth.

Documentary: Emperor penguins

Performed through the darkness of the world’s harshest winter, the breeding ordeal of the Emperor penguin defies belief.

Adèlie penguins

Adèlie penguins spend most of their lives adrift on the frozen sea.

The Snares: A pristine paradise for penguins

The subantarctic Snares Islands are home to millions of albatrosses, shearwaters, prions and penguins, and are considered one of the least modified terrestrial ecosystems on earth.